The Lupus Book: A Guide for Patients and Their Families, Third Edition (19 page)

Read The Lupus Book: A Guide for Patients and Their Families, Third Edition Online

Authors: Daniel J. Wallace

her she was too young to have heart disease, gave her antacids, and sent

her home after obtaining a normal electrocardiogram. When the pain per-

sisted, she returned to the hospital several hours later. This time, her elec-

trocardiogram showed an evolving heart attack. She was admitted and even-

tually had a three-vessel bypass.

Atherosclerotic heart disease (hardening of the arteries) has become the third

most common cause of death in lupus patients, following complications of kid-

Pants and Pulses: The Lungs and Heart

[101]

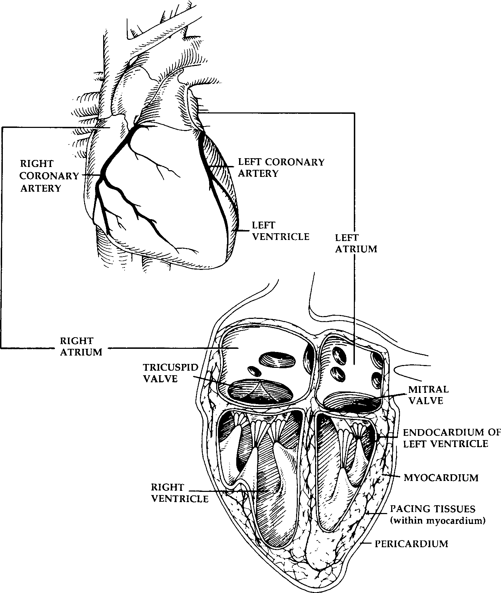

Fig. 14.2.

The Heart

ney disease and infection. Because more young women are surviving other early

organ-threatening complications of lupus, heart complications are now becoming

more prevalent after 10 to 20 years of disease. The side effects of long-term

use of moderate- to high-dose steroids include hypertension, diabetes, hyperli-

pidemia (e.g., high cholesterol), and ultimately premature atherosclerosis. Many healthy-appearing patients of mine in their thirties and forties, such as Bonnie, have developed angina or sustained myocardial infarctions.

[102]

Where and How Can the Body Be Affected by Lupus?

In rare circumstances, active lupus is associated with chest pains (angina

pectoris) from inflammation or vasculitis of the coronary arteries, or

coronary

arteritis

. A coronary angiogram shows the characteristic narrowing of arteries in this unusual condition. It is treated with corticosteroids to prevent a heart attack. Interestingly, children as young as 5 years of age have been reported to develop acute reversible coronary arteritis.

Hypertension

Monitoring blood pressure during each office visit is a good medical practice.

Hypertension, defined as a blood pressure greater than 140/90, is observed in

25 to 30 percent of patients with systemic lupus. The most common causes are

kidney disease and long-term steroid use. There are no special considerations

unique to managing hypertension in lupus patients, since it usually responds to conventional regimens. Untreated or inadequately treated blood pressure can

minimally cause headaches, but hypertension can also lead to stroke, cardiac

failure, and heart attack.

The Electrocardiogram and Conduction Defects

The electrocardiogram (ECG) is an inexpensive, harmless, and readily available

tool that provides the doctor with numerous clues in screening for heart prob-

lems. An ECG detects the heart rate, rhythm, anatomic orientation, and heart

chamber size. Moreover, it can suggest whether the lining of the heart (pericardium) or heart muscle (myocardium) is inflamed and whether the coronary ar-

teries are damaged or in danger. Although one-third of lupus patients may dis-

play abnormalities on an ECG, a normal ECG does not rule out heart disease.

An ECG can also assess the heart’s pacing system, which may be abnormal

in lupus patients. Ten percent of patients with systemic lupus have pacing ab-

normalities or electrical conduction defects that lead to palpitations or missed beats as a result of inflammation or scarring of the heart tissue. The heart’s

electrical or pacing mechanism travels through this damaged tissue, and these

abnormalities result when electrical signals are interrupted.

Lupus present at birth (neonatal lupus) can be characterized by varying de-

grees of heart blockage, since autoantibodies (e.g., anti-Ro) cross the placenta and can damage fetal pacing tissues. Conduction abnormalities in the heart may

be treated with drugs that control the resulting arrhythmia, but insertion of a pacemaker is occasionally required. (See Chapter 22 for a more complete discussion of neonatal lupus.)

Summing Up

Lupus patients frequently complain of chest pain that may or may not be related to heart disease. The sources of true cardiac pain most frequently involve the

Pants and Pulses: The Lungs and Heart

[103]

lining of the heart, which rarely points to a serious disorder. Myocardial disease, which involves the heart muscle, is often serious and may include inflammation

in the form of myocarditis or heart muscle dysfunction, which occasionally

produces congestive heart failure. In patients with antiphospholipid antibodies or the circulating lupus anticoagulant, the inner surface of the heart is predisposed to developing vegetations. This may lead to valve damage or stroke.

Coronary artery disease and high blood pressure appear prematurely in patients

taking steroids for the long-term treatment of lupus. It is essential that doctors take complaints of chest pain seriously and establish its source in order to treat it properly. Finally, the pacing mechanism of the heart can be impaired by

scarring from previous inflammation or by the presence of autoantibodies that

preferentially settle in pacing tissue.

Heady Connections: The Nervous

When my patients tell me they feel as though their brains had been fried, I have to know what is going on in order to help them. For many reasons, the central

nervous system (CNS) and its related behavioral changes in lupus are the most

misunderstood and mismanaged aspects of the disease. The numerous signs and

symptoms that are found may indicate any of twelve clinical and behavioral

syndromes associated with systemic lupus. Since all of these syndromes are

managed differently, carefully honed diagnostic skills on the part of your doctor will be important. Working together, patients, allied health professionals, and physicians can optimize the management of nervous system lupus.

HISTORICAL NOTES

Neurologic involvement in lupus patients was first mentioned in 1875 by Moriz

Kaposi, who described altered mental status and coma in a terminal patient. Sir William Osler, often called the father of modern medicine, described several

patients with CNS lupus at the turn of the century. The first modern study

appeared in 1945, and most of the reports through the 1960s dealt with CNS

vasculitis, or inflammation of the blood vessels in the brain. A landmark report from the Massachusetts General Hospital in 1968 reviewed brain sections at

autopsy in twenty-four individuals with lupus and surprisingly concluded that

vasculitis in the brain was quite rare. As a result, for nearly 20 years there was a great deal of confusion regarding the classification of CNS lupus. In the early 1980s, Graham Hughes and his colleagues described an antiphospholipid antibody known as anticardiolipin and were able to show that as many as one-third

of all acute CNS events were due to clots traveling to the brain or formed within the brain and not due to active lupus. This was followed by the description of

cognitive dysfunction as a unique complication of systemic lupus by Judah Den-

Heady Connections: The Nervous System and Behavioral Changes

[105]

burg and his colleagues in the early 1980s. New classification systems of neu-

rologic lupus have been proposed. We review the relevant findings here.

WHAT ARE THE MAJOR NEUROLOGIC

MANIFESTATIONS OF LUPUS?

The principal neurologic manifestations of lupus are shown in Table 15.1. Most

are present in several of the syndromes associated with CNS lupus.

The most common symptom of CNS involvement is

cognitive dysfunction

.

Characterized by confusion, fatigue, memory impairment, and difficulty in ar-

ticulating thoughts, it may be present by itself (discussed in its own section

below) or as a part of active lupus. Cognitive dysfunction may also appear as

a component of vasculitis, lupus headache, and organic brain syndrome, among

other syndromes.

Headaches

are a feature of the ‘‘lupus headache’’ syndrome (discussed later in this chapter), but they can also be a manifestation of cognitive dysfunction, CNS vasculitis, hypertension, or fibromyalgia.

Seizures

result from acute brain inflammation, scarring from prior vasculitis, acute strokes, or reactions to medications used to treat the disease, such as

corticosteroids or high-dose antimalarials.

Altered consciousness

—such as stupor, excessive sleepiness, or coma—is observed with CNS vasculitis, but can be induced by medication or an infectious

process.

Aseptic meningitis

is an acute condition that involves inflammation of the lining of the spinal cord (meningitis), but spinal fluid cultures do not grow out bacteria, viruses, or fungi. This usually indicates either CNS vasculitis or a

reaction to ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil).

On occasion, a patient may develop

paralysis

. The most common causes range from strokes related to lupus anticoagulant clots or paralysis due to clots induced

Table 15.1.

Major Neurologic Manifestations of Lupus

Cognitive dysfunction (e.g., not thinking clearly)

Headache

Seizure

Altered mental alertness (e.g., stupor, coma)

Aseptic meningitis

Stroke

Peripheral neuropathy (e.g., numbness, tingling, burning of the hands and/or feet) Movement disorders

Paralysis

Altered behavior

Visual changes

Autonomic neuropathy (e.g., flushing, mottled skin)

[106]

Where and How Can the Body Be Affected by Lupus?

by antiphospholipid antibody. Vasculitis of the covering of the spinal cord, infection, or bleeding can also induce paralysis.

Movement disorders

such as tremor, writhing motions termed

chorea

, and balance deficits (known as

ataxia

) imply disease in areas of the brain containing the basal ganglia or cerebellum. Almost any of the twelve syndromes discussed

below can be responsible for movement disorders.

Altered behavior

includes psychosis (e.g., losing touch with reality), organic brain syndrome (e.g., including a demented mental state), depression, and confusion. This behavior is differentiated from cognitive dysfunction in that these alterations are obvious to physicians and family, whereas the cognitive changes are usually subtle and often noticed only by the patient. Chemical imbalances,

active disease, infection, or reaction to medication may cause altered behavior, whereas cognitive dysfunction without other symptoms usually derives from a

blood flow abnormality.

When

strokes

are due to lupus, they result from high blood pressure, low platelet counts, antiphospholipid antibodies, and long-term use of steroids with premature atherosclerosis or active vasculitis.

Visual changes

may be caused by inflammation of the optic nerve, clots resulting from antiphospholipid antibodies, medication such as steroids or anti-

malarials, or an uncommon condition known as pseudotumor cerebri (which

involves swelling of the optic nerve).

Finally,

peripheral

or

autonomic nerves

may produce numbness, tingling, or local nerve palsies (e.g., inability to lift up the wrist).

A careful history and thorough physical examination are critical components

of the diagnostic evaluation, which allows physicians to determine which syn-

drome they are dealing with. These syndromes are discussed below.

LUPUS SYNDROMES OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

The manifestations of lupus discussed above can be part of numerous syn-

dromes. This section examines how they look clinically and reviews the man-

agement of the twelve principal CNS syndromes due to lupus.

Central Nervous System Vasculitis

Elyse developed a rash while sunbathing with her high school friends.

When it did not go away, her mom took her to see their family doctor,

who ultimately diagnosed lupus. She was slightly anemic and had a small

amount of protein in her urine. Upon taking 20 milligrams of prednisone

daily, her tests started to improve and her rash disappeared. Three weeks

later, she caught a flu that was going around, and a few days later, began

noticing difficulty concentrating and connecting her thoughts. She had a

low-grade fever which quickly rose to 104ЊF. Dr. Baker started her on

Heady Connections: The Nervous System and Behavioral Changes

[107]

antibiotics and a decongestant. However, Elyse developed severe headaches

and a stiff neck; she also started convulsing. She was admitted to the hos-

pital. A rheumatologist and neurologist were called in to see her in con-

sultation. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was normal, but her