The Man Who Saw a Ghost: The Life and Work of Henry Fonda (36 page)

Read The Man Who Saw a Ghost: The Life and Work of Henry Fonda Online

Authors: Devin McKinney

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Arts & Literature, #Actors & Entertainers, #Humor & Entertainment, #Movies, #Biographies, #Reference, #Actors & Actresses

It begins in Maude’s living room, where the indomitable heroine (Bea Arthur) has established a campaign headquarters. The campaign: Henry Fonda for president. Maude has conceived it in the midst of a manic depression, but she is also motivated by a genuine disgust with American politics.

Only, Fonda has not been informed of his candidacy; and Maude’s husband, Arthur, tells her it’s stupid to nominate an actor for president. When Maude asks whom

he

wants for president, and Arthur says Ronald Reagan, the studio audience explodes with laughter.

The campaign hurtles forward. Maude’s grandson says Henry has won a mock election at school (“He clobbered Tony Orlando and Dawn”). Maude advances Henry’s daughter Jane as his perfect running mate. Then, shockingly, the fantasy takes form: Drawn in by a false invitation, Henry Fonda is at the doorstep. All stare in astonishment as he towers over them, a wintry monument in a Burberry coat.

The truth comes out. Somewhat aghast, Fonda protests that he knows nothing about being president; that he is unqualified and inexperienced.

“Mr. Fonda,” Maude says, “you have something that no other candidate has … spiritual honesty. Mr. Fonda, you are the quintessential American, and the only one who can bring to this country the leadership it so desperately needs.”

Henry informs Maude that she has, essentially, mistaken a man for a phantom. The words are sensible, but they ignore the degree to which, even if he cannot be the president of our waking lives, he has become the president of our movie fantasy. Maude may be nominating a phantom, but she is also nominating the actor through whom phantoms of idealism continue to exist as potentials.

Before leaving, Fonda repeats the words first uttered by General Sherman after the Civil War, when someone suggested he try for the presidency, and more recently paraphrased by Lyndon Johnson as he declined a second term in the White House.

“If nominated,” Henry Fonda says, “I will not run.”

Four years later, Ronald Reagan is president. It’s Morning in America, and the end of an era.

* * *

Perhaps Fonda’s tenure as dream president ended at the moment it peaked—back in 1964, when

Fail-Safe

opened. Based on a Eugene Burdick–Harvey Wheeler novel serialized in

The Saturday Evening Post

(supposedly it was read by JFK himself), it begins with World War III triggered by a computer malfunction. Filmed in the spring of 1963 and released late the following summer, into a presidential race with world annihilation a central issue, it has the effect both of prophecy and of remembrance. And every representative terror of this last moment before anticipation turns to dread plays out in the face of Henry Fonda’s president.

The movie is a true left-wing conspiracy—directed by old-line New York liberal Sidney Lumet; scripted by blacklistee Walter Bernstein; produced by United Artists vice president and founding member of Hollywood SANE (Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy) Max Youngstein; and headlined by Fonda, who as the film appears is campaigning for LBJ against the putatively bomb-crazy Barry Goldwater.

*

Henry is a longtime proponent of disarmament, having starred in the post-Hiroshima radio drama “Rehearsal,” about the detonation of a superbomb, and narrated an episode of

Eight Steps to Peace

(1957), a series of shorts about the United Nations’ nurturing of détente via weapons treaties.

Despite the weight of its collective convictions,

Fail-Safe

comes across as a pure thriller, dynamic and unrelenting. A U.S. bomber group is reaching its assigned fail-safe points at the borders of Soviet airspace, when a computer blows a chip and transmits an attack code. As American and Soviet officers collaborate in pursuing the bombers, the American president—installed in a White House bunker, connected to the Soviet premier by telephone—tries with increasing desperation to avert the inevitable.

Wait, moviegoers ask, haven’t we seen this?

Fail-Safe

reaches theaters several months behind

Dr. Strangelove,

with virtually the identical plot, and has the sorry fate to be a brilliant movie overshadowed by an exhilarating movie—a movie so fearsomely funny that its nihilisms have the ring of laughter in the cosmic madhouse inhabited by Swift and other comedians of the unthinkable. But

Fail-Safe

is both more dramatic and more earthbound than Kubrick’s spiraling absurdity. Instead of up,

Fail-Safe

goes down—into the bunker, the Pentagon, the gut.

The unnamed president of the novel is a dead ringer for JFK. But as a Kennedy impersonator, Henry Fonda is no Vaughn Meader; to the role of president, he brings only himself. That is plenty. The bomb gives the film its relevance to the Cold War, to the latest election, to the world of 1964, but Fonda is present to give this moment its past—the long ago of Lincoln, and the closer context of twentieth-century American liberalism.

Greil Marcus notes the recurrence of Lincoln imagery in

The Manchurian Candidate,

busts and portraits that appear “more muted and saddened in each successive scene, forced to bear witness to plots to destroy the republic Lincoln preserved.” In

Fail-Safe

, that role of helpless witness is taken by Fonda. Lumet shows him with head bowed and eyes closed, sitting beneath a large clock, bearing the weight of time. If we know Fonda, we know this president is not only listening, he is remembering—thus the sense of pastness. Presentness is in the immediacy of his readings, his shifts between control and panic. You

believe

Fonda in this nightmare setting, as he feels his way through a scenario of destruction no American actor before him has modeled.

First emerging as a tall black shadow advancing down a hallway, the president is seen from behind as his young interpreter stares at the back of his neck, the private face a silver smear in the elevator door. From there, the Fonda body is divested of dominance, the face stripped of privacy. With Fonda confined to the bunker, Lumet uses his star’s height and slimness geometrically, and then bores in with close-ups, huge views from the vantage of a mesmerized fly, as Fonda attempts to negotiate apocalypse by phone.

His eyes become a register of the film’s action, “a reproach to worldly vanities.” Shouting into the hot line, the president asks if it’s possible that one of the fighters might reach its target; when it’s announced that it is, Lumet cuts to a single Fonda eye filling half the frame. In the Pentagon, a pitiless strategist (Walter Matthau) argues for an all-out nuclear strike. “History demands it,” he intones; at the mention of “history,” Fonda’s eyes open and his head snaps up. Contemplating the casualties, Fonda asks, “What do we say to the dead?” There is history behind this moment—both the country’s and the actor’s: When Fonda invokes a responsibility to the departed, it is something very close to a statement of soul.

The moment that fulfills the story and creates continuity with the past comes when the president commits himself to the only act of good faith he can offer. If Moscow is destroyed, he swears, he will order the bombing of New York City—where, in addition to eight million people, his own wife happens to be. Fonda says the words haltingly, as if not trusting the sound of his own voice; and as he does, he covers his face with his hand, shadowing his features from the audience’s view.

It’s one of his great scenes. With nothing but a hand, a voice, and a shadow, past and present are joined, and epiphany crafted. All the submerged intensities of Fonda’s performing history return to fill the scene, to expand its dramatic and political contexts. At the same time, acting out a world-changing ending—imagining the moment when the lid flies off—Fonda holds his hand exactly where the third bullet will, a few months later, enter John Kennedy’s brain as he rides in an open car.

* * *

We’d like to plumb the moment, take it apart, find its cogs and springs. But it’s impossible: We cannot quite “see” what we are seeing. Rather, we feel what we are not seeing—that hum of history, that Lincoln tone still thrumming beneath the machine noise of

Fail-Safe,

of American life as it now is, as it is about to become; a heroism that hates to kill, that instead of boasting “Bring it on” asks, “What do we say to the dead?”

That is the agenda, open and urgent in Lincoln’s America, that has become all but invisible in ours, and which Fonda, in his hiddenness, revives for us. At the eve of world war,

Young Mr. Lincoln

sounded the pure and decisive tone of myth, originating within Eisenstein’s “womb of national spirit.” The tone sang of integrity, equality, beneficent destiny; of affirmation against darkening skies. And it would sound but once.

Yet it persists as memory. Henry Fonda helps to sustain it in the dark of the movie mind, while the presidents of his time transform and deform it in the bright light of the arena. After

Young Mr. Lincoln

, no actor is more identified with the presidential role than Fonda, and Fonda is inconceivable as any other kind of president than Lincoln—that bearer of burdens who, when he looks past the faces of ordinary folk, sees eternity looking back. Lincoln was one of the very few men to ever suggest this depth in our White House, and Fonda is fit to represent him, because damned if he doesn’t act like he knows some of that burden.

The older he has grown, the more Fonda’s face has become the picture of memory, the more those Lincoln tones are the plaintive music of his voice. He need only present himself for us to know the ache, sense the hidden, feel that other, heroic past—just as if it truly happened, as if we were there when it happened.

As if it might happen again: even now, today.

10

He Not Busy Being Born

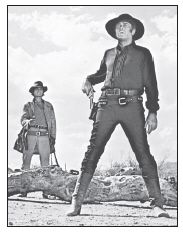

Once Upon a Time in the West

On a ranch in California’s Conejo Valley, some fifty miles northwest of Hollywood, Henry is trying to shoot a movie—a Western called

Welcome to Hard Times.

“I’ve made lots of westerns here,” he tells a reporter, “but it won’t be long before even this place is gone.”

Just over the rise, bulldozers roar, clearing acres earmarked for the planned suburban community of Thousand Oaks. How the West was won, phase three.

* * *

The 1960s are about novelty, evolution, reinvention—in one word, transformation. The works and acts of visionaries as different as Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Beatles, Muhammad Ali and Norman Mailer, James Brown and Jane Fonda have in common a desire to destroy the accepted limits on social behavior and human capability. The decade’s defining figures are determined to live up to the transformative demands they have set themselves; that, and the enormity of popular response to this wholesale questioning of the traditional, is what makes the 1960s a glorious rupture in our recent time.

But for others, tradition is life. A man inclined to prize old values and protect old wounds is bound to feel he was not made for these days. Venerated by one segment of society, he may find himself the target of another, one whose faith is defined in a line of Bob Dylan’s: “He not busy being born is busy dying.”

This man may feel that even his children are hastening that end. By decade’s end, “Kill your parents” has become the Dylan line’s sinister complement. Parricide, the unvoiced desire, finds voice in some widely noted words and images—Jim Morrison climaxing a Doors song by raping his mother and murdering his father; 1968’s

Wild in the Streets,

in which a nineteen-year-old becomes president and parents are force-fed LSD in pogroms; Weatherman Bill Ayers’s declaration, “Bring the revolution home. Kill your parents. That’s where it’s really at”; or Charles Manson warning straight America that its children are

“running in the streets—and they are coming right at you!”

* * *

In 1966, Henry Fonda becomes an institution. His sixtieth film,

A Big Hand for the Little Lady,

is released in June; later that month, a party is held at New York’s swanky L’Etoile restaurant to mark his third decade of Hollywood stardom. The celebration serves as overture to a Fonda film retrospective at the New Yorker Theater, and as coda to his stage comeback in a hit comedy,

Generation,

now closing after three hundred performances.

The play has more than done its business, and Henry’s reviews have been impeccable. But it may chafe him to find anniversaries and retrospectives suddenly abounding. In a piece accompanying the retrospective, Peter Bogdanovich writes: “Were he never to play another role, his Lincoln, his Mister Roberts, his Earp, his Tom Joad would have immortalized him … as a special, most individual aspect of The American.” The words are truthful and sincere, and sound like an elegy.

Right now, the Fonda kids are more to the point. As Henry celebrates his thirty years in movies, Peter—currently on drive-in screens as a drug-taking, church-wrecking Hell’s Angel—is arrested in Los Angeles in connection with a quantity of marijuana. Across the ocean, Jane—now an expatriate actress married to a director of glossy erotica—sues

Playboy

magazine for publishing nude photos of her.