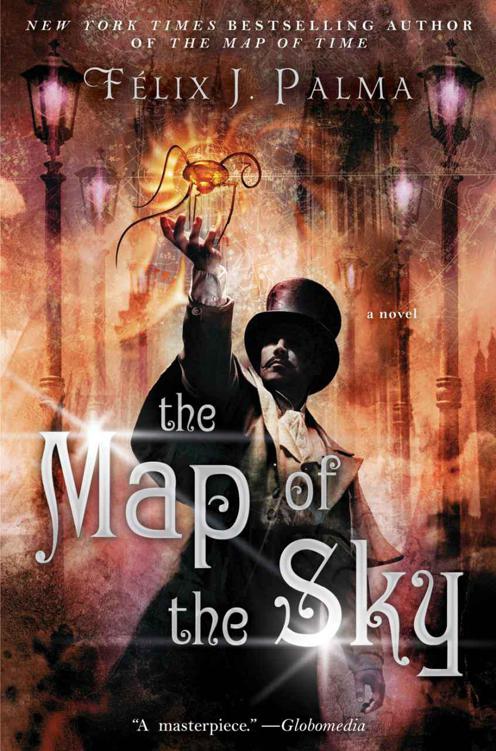

The Map of the Sky

Read The Map of the Sky Online

Authors: Felix J Palma

Thank you for purchasing this Atria Books eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Atria Books and Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

CONTENTS

O

N THE COSMIC SCALE, ONLY THE FANTASTIC HAS A POSSIBILITY OF BEING TRUE.

Teilhard de Chardin

I

T IS A STUPID PRESUMPTION TO GO ABOUT DESPISING AND CONDEMNING AS FALSE ANYTHING THAT SEEMS TO US IMPROBABLE.

Montaigne

“W

HAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT

M

ARS

?”

ASKED

G

USEV

. “I

S IT INHABITED BY PEOPLE OR MONSTERS

?”

Aleksey Tolstoy

W

ELCOME, DEAR READER, AS YOU PLUNGE VALIANTLY INTO THE THRILLING PAGES OF OUR MELODRAMA, WHERE YOU WILL FIND ADVENTURES THAT TEST YOUR SPIRIT AND POSSIBLY YOUR SANITY!

I

F YOU BELIEVE OUR PLANET HAS NOTHING TO FEAR AS IT SPINS IN THE VAST UNIVERSE, YOU WILL PRESENTLY LEARN THAT THE MOST UNIMAGINABLE TERROR CAN REACH US FROM THE STARS.

I

T IS MY DUTY TO WARN YOU, BRAVE READER, THAT YOU WILL ENCOUNTER HORRORS THERE, WHICH YOUR INNOCENT SOUL COULD NEVER HAVE IMAGINED WERE GOD’S CREATIONS.

I

F OUR TALE DOES NOT TAKE YOU TO THE DIZZIEST HEIGHTS OF EXHILARATION, WE WILL REFUND YOUR FIVE CENTS SO YOU MAY SPEND THEM ON A MORE EXCITING ADVENTURE, IF SUCH A THING EXISTS!

“W

HAT DO YOU SUPPOSE THAT THING IS,

P

ETERS

?”

ASKED ONE OF THE OTHER SAILORS, A MAN CALLED

C

ARSON.

T

HE

I

NDIAN REMAINED SILENT FOR A FEW MOMENTS BEFORE REPLYING, CONTEMPLATING WHETHER HIS COMPANIONS WERE READY FOR THE REVELATION HE WAS ABOUT TO SHARE WITH THEM.

“A

DEVIL

,”

HE SAID IN A GRAVE VOICE

. “A

ND IT CAME FROM THE STARS

.”

H

ERBERT

G

EORGE

W

ELLS WOULD HAVE PREFERRED

to live in a fairer, more considerate world, a world where a kind of artistic code of ethics prevented people from exploiting others’ ideas for their own gain, one where the so-called talent of those wretches who had the effrontery to do so would dry up overnight, condemning them to a life of drudgery like ordinary men. But, unfortunately, the world he lived in was not like that. In his world everything was permissible, or at least that is what Wells thought. And not without reason, for only a few months after his book

The War of the Worlds

had been published, an American scribbler by the name of Garrett P. Serviss had the audacity to write a sequel to it, without so much as informing him of the fact, and even assuming he would be delighted.

That is why on a warm June day the author known as H. G. Wells was walking somewhat absentmindedly along the streets of London, the greatest and proudest city in the world. He was strolling through Soho on his way to the Crown and Anchor. Mr. Serviss, who was visiting England, had invited him there for luncheon in the sincere belief that, with the aid of beer and good food, their minds would be able to commune at the level he deemed appropriate. However, if everything went according to plan, the luncheon wouldn’t turn out the way the ingenuous Mr. Serviss had imagined, for Wells had quite a different idea, which had nothing to do with the union of like minds the American had envisaged. Not that Wells was proposing to turn what might otherwise be a pleasant meal into a council of war because he considered his novel a

masterpiece whose intrinsic worth would inevitably be compromised by the appearance of a hastily written sequel. No, Wells’s real fear was that another author might make better use of his own idea. This prospect churned him up inside, causing no end of ripples in the tranquil pool to which he was fond of likening his soul.

In truth, as with all his previous novels, Wells considered

The War of the Worlds

an unsatisfactory work, which had once again failed in its aims. The story described how Martians possessing a technology superior to that of human beings conquered Earth. Wells had emulated the realism with which Sir George Chesney had imbued his novel

The Battle of Dorking,

an imaginary account of a German invasion of England, unstinting in its gory detail. Employing a similar realism bolstered by descriptions as elaborate as they were gruesome, Wells had narrated the destruction of London, which the Martians achieved with no trace of compassion, as though humans deserved no more consideration than cockroaches. Within a matter of days, our neighbors in space had trampled on the Earth dwellers’ values and self-respect with the same disdain the British showed toward the native populations in their empire. They had taken control of the entire planet, enslaving the inhabitants and transforming Earth into something resembling a spa for Martian elites. Nothing whatsoever had been able to stand in their way. Wells had intended this dark fantasy as an excoriating attack on the excessive zeal of British imperialism, which he found loathsome. But the fact was that now people believed Mars was inhabited. New, more powerful telescopes like that of the Italian Giovanni Schiaparelli had revealed furrows on the planet’s red surface, which some astronomers had quickly declared, as if they had been there for a stroll, to be canals constructed by an intelligent civilization. This had instilled in people a fear of Martian invasion, exactly as Wells had described it. However, this didn’t come as much of a surprise to Wells, for something similar had happened with

The Time Machine,

in which the eponymous artifact had eclipsed Wells’s veiled attack on class society.

And now Serviss, who apparently enjoyed something of a reputation

as a science journalist in his own country, had published a sequel to it:

Edison’s Conquest of Mars.

And what was Serviss’s novel about? The title fooled no one: the hero was Thomas Edison, whose innumerable inventions had made him into something of a hero in the eyes of his fellow Americans, and subsequently into the wearisome protagonist of every species of novel. In Serviss’s sequel, the ineffable Edison invented a powerful ray gun and, with the help of the world’s nations, built a flotilla of ships equipped with antigravitational engines, which set sail for Mars driven by a thirst for revenge.

When Serviss sent Wells his novel, together with a letter praising Wells’s work with nauseating fervor and almost demanding that he give the sequel his blessing, Wells had not deigned to reply. Nor had he responded to the half dozen other letters doggedly seeking Wells’s approval. Serviss even had the nerve to suggest, based upon the similarities and common interests he perceived in their works, that they write a novel together. After reading Serviss’s tale, all Wells could feel was a mixture of irritation and disgust. That utterly childish, clumsy piece of prose was a shameless insult to other writers who, like himself, did their best to fill the bookshop shelves with more or less worthy creations. However, Wells’s silence did not stanch the flow of letters, which if anything appeared to intensify. In the latest of these, the indefatigable Serviss begged Wells to be so kind as to lunch with him the following week during his two-day visit to London. Nothing, he said, would make him happier than to be able to enjoy a pleasant discussion with the esteemed author, with whom he had so much in common. And so, Wells had made up his mind to end his dissuasive silence, which had evidently done no good, and to accept Serviss’s invitation. Here was the perfect opportunity to sit down with Serviss and tell him what he really thought of his novel. So the man wanted his opinion, did he? Well, he’d give it to him, then. Wells could imagine how the luncheon would go: he would sit opposite Serviss, with unflappable composure, and in a calm voice politely masking his rage, would tell him how appalled he was that Serviss had chosen an idealized version of Edison as the hero of his novel. In

Wells’s view, the inventor of the electric lightbulb was an untrustworthy, bad-tempered fellow who created his inventions at the expense of others and who had a penchant for designing lethal weapons. Wells would tell Serviss that from any point of view the novel’s complete lack of literary merit and its diabolical plot made it an unworthy successor to his own. He would tell him that the message contained in its meager, repugnant pages was diametrically opposed to his and had more in common with a jingoistic pamphlet, since its childish moral boiled down to this: it was unwise to step on the toes of Thomas Edison or of the United States of America. And furthermore he would tell him all this with the added satisfaction of knowing that after he had unburdened himself, the excoriated Serviss would be the one paying for his lunch.