The Mapmaker's Wife (14 page)

Read The Mapmaker's Wife Online

Authors: Robert Whitaker

Tags: #History, #World, #Non-Fiction, #18th Century, #South America

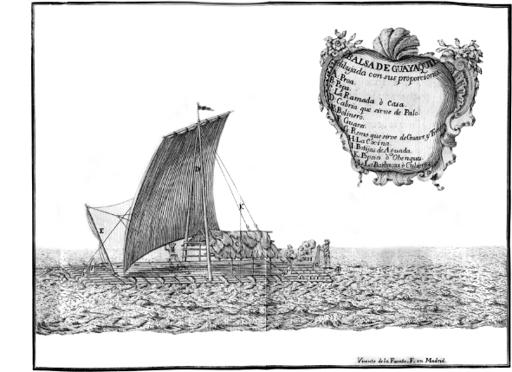

A balsa raft in the Bay of Guayaquil.

From Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa

, Relación histórica del viage a la América Meridional

(1749)

.

After eight such miserable days, they transferred their baggage at Caracol to the backs of seventy mules and immediately found themselves mired in a bog. The mules “at every step sunk almost up to their bellies,” and when they finally reached the Ojibar River, only twelve miles from Caracol, they had to spend the night in a village with the unhappy name of Puerto de Moschitos. Jean Godin and a few others, in an effort to find relief from the insects, “stripped themselves and went into the river, keeping only their heads above water, but the face, being the only part exposed, was immediately covered with them, so that those who had recourse to this expedient, were soon forced to deliver up their whole bodies to these tormenting creatures.”

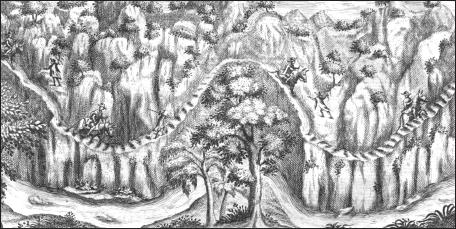

They now began their climb into the mountains, and while they had the pleasure of passing many beautiful waterfalls, some more than 300 feet high, the path was so narrow that as they rode on the mules, they frequently banged “against the trees and rocks,” giving them a collection of bruises to go with their multitude of insect bites. They also had to cross swaying bridges strung high over cascading rivers:

The bridges [are] made with cords, bark of trees, or lianas. These lianas, netted together, form an aerial gallery, which is suspended from two large cables of similar materials, the extremities of which are fastened to branches of trees on opposite banks. Collectively the whole of these singular bridges resembles a fisher’s net, or rather an Indian hammock, extending from one to the other side of the river. As the meshes of this net are very wide, and would suffer the foot to go between them, a sort of flooring is superimposed, consisting of branches and shrubs. It will readily be conceived, that the weight of this network, but especially that of the passenger, must give a considerable curve to the bridge, and when, in addition, one reflects that the traveler passing it is exposed to great oscillations, to which it is incident, particularly when the wind is high, and he reaches near the middle, this kind

of bridge, which is oftentimes thirty fathoms long, [it] must needs have something frightful in its aspect. The natives, however, who are far from being naturally intrepid, pass such bridges on the trot, with their loads on their shoulders, together with the saddles of the mules, which cross the river by swimming, and laugh at the timidity of the traveller who hesitates to venture [across].

Huts on the Guayaquil River.

From Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa

, Relación histórica del viage a la América Meridional

(1749)

.

Even more frightening, they discovered that their lives were now dependent on their mules’ having good judgment and a steady step. The muddy trail was filled with holes, “near three quarters of a yard deep, in which the mules put their fore and hind feet, so that sometimes they draw their bellies and riders’ legs along the ground. Should the creature happen to put his foot between two of these holes, or not place it right, the rider falls, and, if on the side of the precipice, inevitably perishes.” They spent two or three days in this manner, at times inching along ledges that looked out over “deep abysses,” which, Ulloa and Juan confessed, filled their “minds with terror.” They reached an altitude of more than 10,000 feet, having

ascended the western cordillera of the Andes,

*

and then, in the early afternoon of May 18, they crossed over a mountain pass called Pucara. Now they began their descent into the valley below, the slopes so steep and muddy that the mules slid down on their bellies, with their forelegs stretched out, moving with the “swiftness of a meteor.” All that the startled riders—Ulloa, Juan, Louis Godin, Jussieu, Senièrgues, Hugo, Morainville, Verguin, Couplet, and Jean Godin—could do was hang on for dear life.

They spotted the village of Guaranda just before sunset. A sorry-looking bunch of travelers, the lot of them bruised, muddied, and exhausted, they felt overwhelmed with relief when the corregidor of the town came out to greet them. A priest then appeared, leading a parade of Indians boys waving flags, dancing, and singing, and as the expedition entered the town, bells were rung, “and every house resounded with the noise of trumpets, tabors and pipes.” When they expressed their surprise, they were informed that such a reception was not at all unusual, but was given to all who entered the town. It was Guaranda’s way of “paying congratulations” to those who had survived the perilous journey from Guayaquil.

They now had to travel north for 120 miles to reach Quito. They left Guaranda on May 21, skirted around the flanks of snow-capped Mount Chimborazo, a volcano more than 20,000 feet tall, and spent that first night in a stone cave called Rumi Machai. Over the course of the next week, they stumbled across the ruins of an Inca palace, awoke several mornings in huts covered with ice, crossed several deep chasms formed by earthquakes, and then, on May 29, at dusk, they rode into Quito. There they were greeted with every civility by the president of the Quito Audiencia,

†

Dionesio de Alsedo y Herrera, their journey of twelve months having finally come to an end.

B

OUGUER AND

L

A

C

ONDAMINE

fared even worse in their travels. Bouguer, after leaving La Condamine at the Rio Jama, had suffered a miserable journey down the coast to Guayaquil, the trail so swampy that even mounted on a horse, he was often up to his knees in water. He reached Guayaquil three days after the others had departed, and he then followed in their wake all the way to Quito. His travel, however, was slowed by his poor health, and he did not arrive until June 10.

At first, La Condamine’s trip had not been too unpleasant. After he and Bouguer split up, he had traveled north in a sea canoe, hugging the shoreline and stopping to determine the longitude of landmarks along the coast, such as the Cape of San Francisco. He was filling out the map that he and Bouguer had begun in Manta, and he continued his sea travels for more than 120 miles, until he reached Esmeraldas, a town populated primarily by free Negroes, the descendants of slaves who had escaped from a nearby shipwreck fifty years earlier. There he had the good fortune to meet the governor of the province, Pedro Maldonado, who had heard from administrators in Quito about the French mission. Maldonado was about the same age as La Condamine, and he shared his enthusiasm for exploration and science. A lasting friendship was born, and Maldonado told La Condamine of his plans to build a road from Esmeraldas to Quito—a route, he said, that La Condamine could now take.

The first leg of this 140-mile trip was up the Esmeraldas River. The river was so named because the conquistadors had come upon natives mining gems from its banks, and La Condamine, ever the indefatigable scientist, mapped its every turn. After that, he plunged into the jungle. Maldonado’s vision for a road to Quito was just that—a dream for the future—and La Condamine had to bushwhack his way through the forest. His Indian guides cut their way through the brush with axes, La Condamine carrying his compass and thermometer in his hands, “more often than not on foot

rather than horseback.” It rained every afternoon, La Condamine dragging “along several instruments and a large quadrant, which two Indians had a hard time carrying.” The dense foliage slowed their progress, and yet La Condamine turned even this to his advantage, collecting “in this vast jungle a large number of singular plants and seeds,” which he looked forward to giving to Jussieu upon his arrival in Quito. His mood turned sour only after he was abandoned by his guides. He had but one horse to help him carry his goods, which consisted of a hammock, a suitcase of clothes, and his treasured instruments, which he was loathe to leave behind.

*

He was also nearly out of food: “I remained for eight days in this jungle. Powder and other provisions became scarce. I subsisted on bananas and other native fruits. I suffered a fever which I treated by a diet, which was recommended to me by reason and ordered by necessity.”

He emerged from this solitude by “following the crest of a mountain,” coming upon a narrow path much like the one that Godin and the others had followed into the Andes from Guayaquil. The trail passed waterfalls and crossed ravines “carved by torrents of melting snow,” and La Condamine, like the others, found the liana bridges nerve-racking. Halfway up the Andes, he came upon several Indian villages—Niguas, Tambillo, and Guatea—where the natives, known as

Los Colorados

, colored themselves with red paint. In the last of these, he obtained new guides and mules. Because he had no money left, he was forced to leave behind his suitcase and quadrant as a guarantee that someone would return and pay for these services. Los Colorados led him to Nono, a village high in the Andes, where a Franciscan monk supplied him with all that he needed for the rest of his journey. La Condamine made his way ever higher into the mountains, stopping at times to catch his breath. The path scooted around the northern flank of boulder-strewn Mount Pichincha, a volcano that topped 15,700 feet. As he

reached the highest point on the trail, the clouds lifted, and suddenly he could see for miles:

I was seized by a sense of wonder at the appearance of a large valley of five to six leagues wide, interspersed with streams which joined together to form a river. I saw as far as my sight could see cultivated lands, divided into plains and prairies, green spaces, villages and towns surrounded by bushes and gardens. The city of Quito, far off, was at the end of this beautiful view. I felt as if I had been transported to the most beautiful of provinces in France, and as I descended I felt the imperceptible change in climate by going from extreme cold to the temperature of the most beautiful days in May.

His journey had come to an end. It was June 4, 1736, and now La Condamine and the others could begin the daunting task of measuring a degree of latitude in this rugged terrain.

*

Mount Pelée is 4,586 feet tall.

*

Although La Condamine is unclear on this point, apparently the

Portefaix

had not been authorized to sail to a Spanish port.

*

The Andes in this part of South America consists of two mountain ranges, or cordilleras, separated by a valley twenty-five to thirty-five miles wide.

†

The Viceroyalty of Peru was divided up into a number of administrative districts known as

audiencias

. The Audiencia de Quito governed a territory about five times the present size of Ecuador, stretching from the Pacific to the Amazon.

*

La Condamine writes of being alone once the guides abandoned him. It is most likely, however, that he was still accompanied by a personal servant.