The Mapmaker's Wife (16 page)

Read The Mapmaker's Wife Online

Authors: Robert Whitaker

Tags: #History, #World, #Non-Fiction, #18th Century, #South America

On June 14, La Condamine finally wrote to Alsedo, telling him that he was in town and would like to visit. But the letter did not contain the apology that Alsedo expected, and the audiencia president responded with an icy warning: La Condamine was to comport himself

“within the boundaries” set by his passport, he was to refrain from investigating matters that had not been approved by the king, and he should have come to the audiencia palace earlier to explain himself. Why had he separated from his companions in Manta, and why was he now lodged apart from them? Did he realize this violated the terms of his passport? Alsedo also fired off a missive to the viceroy, assuring the Marqués de Villagarcía,

“I will always be suspicious of the foreigners, and I have taken precautions that would be considered necessary to protect the security and interests of Spain.”

This ill will did not portend well for the future success of the mission, and yet La Condamine, who seemed to have a particular fondness for diplomatic dustups, responded in a way that could only exacerbate matters. In a few days, he informed Alsedo, he was planning to travel to Nono with Ramon Maldonado, Pedro’s brother, in order to view the June 21 solstice. This village, he noted rather snootily,

“would be found near or next to the equator,” where he was supposed to do his work, but if the president did “not like it that I take a walk there with Don Ramon, I will not go.” La Condamine was holding up his passport to trump Alsedo—theirs was a sanctioned trip to the equator, after all—and, pleased that he could call on Philip’s words in this way, he took his trip to Nono. It was, he wrote,

“the first time that I had emerged from my retreat.”

When he returned, Alsedo was—as La Condamine subtly put it in his journal—“indisposed” toward him. His Jesuit hosts warned him not to take this dispute any further, particularly since the expedition had other problems to solve. First among them was money. Godin had expected that there would be new letters of credit waiting for them in Quito, but not a single letter from Maurepas or any one else in France had reached the city, even though more than a year had passed since they had departed from La Rochelle. Godin

had immediately asked Alsedo for an advance, but the audiencia president had refused—4,000 pesos was all that France had guaranteed. Something needed to be done, and with the rector of the Jesuits, Father Hormaegui, acting as a go-between, La Condamine arranged to see the president.

There was every reason to believe this meeting would go badly. Honor was of such overwhelming importance in colonial Peru that men waged duels over squabbles much more trivial than this one. La Condamine was famously stubborn, unlikely to back down just because it might make things proceed more smoothly. Yet once he arrived at the audiencia palace and bent forward ever so slightly in greeting—about as much deference as La Condamine could muster—the bad feelings began to dissipate. La Condamine explained that it was because of his lack of decent clothes that he had not come to pay his respects right away: How could he call on an honorable representative of the king of Spain in such a state? He had needed to wait until a servant had fetched his suitcase and Bouguer, coming in from Guayaquil, had arrived with his trunk.

“I completely satisfied the President on all counts,” La Condamine happily concluded, and indeed, Alsedo was so charmed that he insisted that La Condamine, from that moment forward, become a frequent dinner guest. Alsedo even begged the Jesuits to keep their doors open until 8:30

P.M

., past their usual hour of closing, so that he and La Condamine could enjoy an after-dinner brandy together. Theirs was a budding friendship, and La Condamine, at ease now in Quito, opened a shop of sorts in the Jesuit rectory, putting up for sale an array of his personal belongings in order to raise money for the expedition. This was just the type of contraband activity that Alsedo had been worried about, but times had changed, and he quickly became one of La Condamine’s best customers.

The president was not alone in enjoying the new shopping opportunity—many of Quito’s elite found their way to the rectory. Ramon Maldonado bought a number of books, including a history of the French Academy of Sciences, while his wife picked out some diamonds and emeralds. Pedro Maldonado acquired some elegantly

embroidered cloth. Alsedo, for his part, purchased fine Holland shirts and cotton clothes. Others bought bedsheets, silk stockings, gloves, switchblades and other knives, needles, gunflints, jewelry, a “prize gun” of La Condamine’s, a diamond-encrusted cross of Saint Lazarus, and various French novelties and trinkets. Tomás Guerrero, a member of the Quito town council, was a regular customer, as was José Benavides, a rich property owner. The flow of goods out of the Jesuit rectory was such that a resale market opened: Alsedo put an assistant, Manuel de Escabo, in charge of buying things and reselling them in Otavalo, while another prominent Spaniard, Antonio Suarez, simply resold the contraband in his shop in Quito.

All in all, La Condamine had turned a difficult situation to his advantage. He had had the good sense to sell his goods at a price that provided the elite in Quito with a fair deal and even offered them the possibility of turning a profit. After a bungled beginning, he had found a way to get along with Quito’s high society, and the expedition was now able to go about its business unfettered by any overly scrupulous supervision, at least as long as Alsedo was president.

A

LTHOUGH THE

C

ASSINIS

, in their earlier work, had always measured a degree of latitude along a north-south meridian, the French savants were considering measuring both a degree of latitude and one of longitude on this mission. Not only would the east-west measurement enable them to calculate the earth’s circumference along its equatorial axis, but by comparing the two (a degree of latitude versus one of longitude), they might be able to answer the question of the earth’s shape from their

“operations alone without needing to refer to anyone else’s,” La Condamine noted. According to Newton’s theory, the diameter of the earth along the equatorial plane was thirty-four miles longer than it was along an axis through the poles, and thus a degree of longitude at the equator should be ever-so-slightly longer than a degree of latitude. If, as the Cassinis believed, the earth was elongated at the

poles, then the reverse would be true—a degree of latitude would be slightly longer than a degree of longitude. Taking both measurements was another way of resolving the question of the earth’s shape, and it would complement their initial plan of comparing a degree of latitude at the equator to the one measured by the Cassinis in France or by Maupertuis in Lapland.

Godin, Bouguer, and La Condamine had a basic plan for determining a degree of longitude. After using triangulation to mark off a distance of seventy miles or so along the equator, they could synchronize pendulum clocks stationed at the two ends of this measured line. This synchronization could be done with a luminous signal, such as the flash from a cannon, or, if a mountain obstructed their sight, with a sonic signal, such as the sound of cannon fire. With their clocks in harmony, observers could train their sights on a particular star and mark the time—at each station—that it reached its halfway point in its east-west passage across the sky. The difference in time would tell them how far apart they were in degrees of longitude, and since they would also know the distance between the two stations in miles (or toises), they would have all the information they needed to calculate the circumference of the earth at the equator.

Although this was in theory a relatively straightforward process, Godin, Bouguer, and La Condamine were not of one mind about whether it could be done with sufficient accuracy to produce a useful result. The difference between a degree of longitude and one of latitude at the equator would be very small, less than half a mile. Rather than try to resolve that question now, Godin decided that they should set down a baseline that could be used for triangulation in either a north-south or an east-west direction. In August, Verguin and several of the others scouted around Quito for terrain that might be suitable for this task, and they settled on the plain of Cayambe, thirty-five miles north of the city.

The entire group traveled to Cayambe in early September, and while the academicians debated whether it would do—the land was awfully uneven and was divided by two rivers—Couplet fell

gravely ill. He was bled and purged, as was the European custom, and was probably given a dose of local medicine for

mal del valle

, as fever was called in the Quito area. This Peruvian treatment, Ulloa and Juan noted, was rather painful,

“as a pessary, composed of gunpowder, guinea pepper and a lemon peeled, is insinuated into the anus, and changed two or three times a day, till the patient is judged to be out of danger.” Despite such ministrations (or perhaps because of them), Couplet died on September 17, only two days after the fever set in.

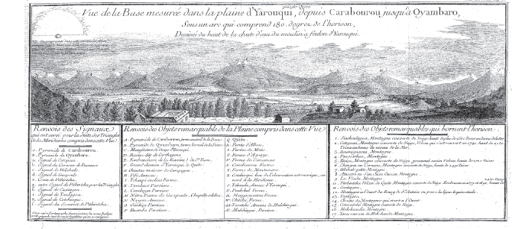

Although the scientists were saddened by this tragedy, they were not at all surprised by it. Everyone had experienced a bout of fever, which could turn deadly at a moment’s notice. Indeed, no sooner had they buried Couplet than Juan fell ill. Someone was always sick, death was an ever-present possibility, and there was nothing for the others to do but go on with their work. Cayambe, they decided, would not serve their purposes well, so they moved their baseline operations to the plain of Yaruqui, twelve miles northeast of Quito. Although the terrain was not as hilly at Yaruqui as at Cayambe, they would need to cross a fifty-foot ravine, which presented a formidable challenge.

It was essential that they determine the length of the baseline to an excruciating degree of accuracy. This measurement would serve as the first side of the first triangle and thus would be

“the base of the whole work,” Ulloa observed. From the two ends of the baseline, they would then measure the angles to a third point, and this information would enable them to mathematically calculate the length of the other two sides of the triangle. This process could then be repeated over and over again, with a side of the most recently determined triangle serving as the first side of the next one, so that only the length of the initial baseline actually had to be measured. An imprecise measurement here would corrupt all that followed.

Their proposed baseline ran from Oyambaro to Caraburu, the land dropping 760 feet between these two villages. They marked the terminals of the baseline with large millstones, cleared the brush between these two points, and set up a straight path to follow

by carefully aligning intermediate markers every 3,000 feet. As a way of checking their work, they broke into two groups to measure this distance in opposite directions. One group was led by Bouguer, La Condamine, and Ulloa, the other by Godin and Juan, who, after a week of rest, had regained his strength.

Each group employed three twenty-foot-long wooden rods to mark off the distance. They laid the rods, which were color coded to ensure they were always kept in the same order, end to end and moved one rod at a time. By utilizing three rods instead of two (as the Cassinis had done), La Condamine and the others reasoned that there would be less chance that moving a rod to the front would jiggle the others—two stationery rods would be more stable than one. The rods also had thin pieces of copper wire on their ends so that when placed together they would touch at a single contact point, making the measurement more precise. Every possible source of error was considered, the academicians even fretting that changes in temperature or humidity could cause the rods to expand or contract, throwing off their results. Each day they checked the wooden rods with Langlois’s iron toise, which they kept in the shade lest it expand in the hot sun—they needed their ruler to maintain an exact length. Yet another problem was presented by the sloping land. To keep the rods perfectly horizontal, they placed them on sawhorses and used wedges to level them off. When necessary, they utilized a plumb line to move the rods up or down to a new tier, and in this manner they proceeded steplike across the hilly plain.

*

They used this same method to cross the ravine.

As they performed this delicate operation, they had to contend with weather of the most miserable sort. Although the valley south of Quito might have been a pastoral Eden, the environment north of the city was totally different. Few shrubs or plants grew in the sandy soil, Ulloa and Juan reported, and “violent tempests of thunder, lightning and rain” regularly swept down from the mountains.

Such dreadful whirlwinds form here that the whole interval is filled with columns of sand, carried up by the rapidity and gyrations of violent eddy winds, which sometimes produce fatal consequences. One melancholy instance happened while we were there; an Indian, being caught in the center of one of these blasts, died on the spot. It is not, indeed, at all strange, that the quantity of sand in one of these columns should totally stop all respiration in any living creature who has the misfortune of being involved in it.

With the wind constantly blowing their rods askew, it took the French academicians twenty-six days of dawn-to-dusk labor to measure the baseline. Their results, however, were phenomenal. The two groups’ conclusions varied by only

three inches

across a distance of nearly eight miles, and so they split the difference: Their baseline was 6272.656 toises long. They returned to Quito on December 5, confident that they had done this all-important first measurement well.