The Mary Russell Companion (17 page)

Read The Mary Russell Companion Online

Authors: Laurie R. King

Tags: #Mystery; Thriller & Suspense, #Mystery, #Women Sleuths, #Reference, #Writing; Research & Publishing Guides, #Research

Excerpt

I used occasionally to wonder why the otherwise canny folk of the nearby towns, and particularly the stationmasters who sold the tickets, did not remark at the regular appearance of odd characters on their platforms, one old and one young, of either sex, often together. Not until the previous summer had I realised that our disguises were treated as a communal scheme by our villagers, who made it a point of honour never to let slip their suspicions that the scruffy young male farmhand who slouched through the streets might be the same person who, dressed considerably more appropriately in tweed skirt and cloche hat, went off to Oxford during term time and returned to buy tea cakes and spades and the occasional half-pint of bitter from the merchants when she was in residence. I believe that had a reporter from the Evening Standard come to town and offered one hundred pounds for an inside story on the famous detective, the people would have looked at him with that phlegmatic country expression that hides so much and asked politely who he might be meaning.

I digress. When I reached London, the streets were still crowded. I took a taxi (a motor cab, so I hadn‘t to look too closely at the driver) to the agency Holmes often used as his supplier when he needed a horse and cab. The owner knew me—at least, he recognised the young man who stood in front of him—and said that, yes, that gentleman (not meaning, of course, a gentleman proper) had indeed shown up for work that day. In fact, he‘d shown up twice.

“Twice? You mean he brought the cab back, then? I was disappointed, and wondered if I ought merely to give up the chase.

“T’orse ’ad an ‘ot knee, an’ ’e walked ’er back. ’E was about ter take out anuvver un when ’e ’appened t’see an ol’ ’ansom just come in. Took a fancy, ’e did, can’t fink why—’s bloody cold work an’ the pay’s piss-all, ’less you ’appen on t’ odd pair what wants a taste of t’ old days, for a lark. ’Appens, sometimes, come a summer Sunday, or after t’ theatre Sattiday. Night like this ’e ’d be bloody lucky t’get a ha’penny over fare.”

With a straight face, I reflected privately on how his colourful language would have faded in the light of the posh young lady I occasionally was.

“So he took the hansom?”

“That ’e did. One of the few what can drive the thing, I’ll give ’im that.” His square face contemplated for a moment this incongruous juxtaposition of skill and madness in the man he knew as Basil Josephs, then he shook his head in wonderment.

“’Ad ta give ’im a right bugger of an ’orse, though. Never been on a two-wheeler, ’e ’asn ’t, and plug-headed and leather-mouthed to boot. ’Ope old Josephs ’asn’t ’ad any problems,” he said with a magnificent lack of concern, and leant over to hawk and spit delicately into the noisome gutter.

“Well,” I said, “there couldn‘t be too many hansoms around, I might spot him tonight. Can you tell me what the horse looks like?”

“Big bay, wide blaze, three stockin’s with t’ off hind dark, nasty eyes, but you won‘t see ’em—’e ’s got blinkers on,” he rattled off, then added after a moment, “Cab’s number two-ninety-two.” I thanked him with a coin and went a-hunting through the vast, sprawling streets of the great cesspool for a single, worn hansom cab and its driver.

The hunt was not quite so hopeless as it might appear. Unless he were on a case (and Mrs Hudson had thought on the whole that he was not), his choice of clothing and cab suggested entertainment rather than employment, and his idea of entertainment tended more toward London‘s east end rather than Piccadilly or St John‘s Wood.

Still, that left a fair acreage to choose from, and I spent several hours standing under lampposts, craning to see the feet of passing horses (all of them seemed to have blazes and stockings) and fending off friendly overtures from dangerously underdressed young and not-so-young women. Finally, just after midnight, one marvelously informative conversation with such a lady was interrupted by the approaching clop and grind of a trotting horsecab, and a moment later the piercing tones of a familiar voice echoing down the nearly deserted street obviated the need for any further equine examination.

“Annalisa, my dear young thing,” came the voice that was not a shout but which could be heard a mile away on the Downs, “isn‘t that child you are trying to entice a bit young, even for you? Look at him—he doesn’t even have a beard yet.”

The lady beside me whirled around to the source of this interruption. I excused myself politely and stepped out into the street to intercept the cab. He had a fare—or rather, two—but he slowed, gathered the reins into his right hand, and reached the other long arm down to me. My disappointed paramour shouted genial insults at Holmes that would have blistered the remaining paint from the woodwork, had they not been deflected by his equally jovial remarks in kind.

The alarming dip of the cab caused the horse to snort and veer sharply, and a startled, moustachioed face appeared behind the cracked glass of the side window, scowling at me. Holmes redirected his tongue‘s wrath from the prostitute to the horse and, in the best tradition of London cabbies, cursed the animal soundly, imaginatively, and without a single manifest obscenity. He also more usefully snapped the horse‘s head back with one clean jerk on the reins, returning its attention to the job at hand, while continuing to pull me up and shooting a parting volley of affectionate and remarkably familiar remarks at the fading Annalisa. Holmes did so like to immerse himself fully in his rôles, I reflected as I wedged myself into the one-person seat already occupied by the man and his garments.

“Good evening, Holmes,” I greeted him politely.

(For more background and a longer excerpt, see this book’s page on the Laurie R. King website.

A Letter of Mary

Russellisms

“My dear Holmes, this verges on

deductio ad absurdum

.”

* *

Whether my reaction was one of suppressed hysterical laughter or the urge to commit mass ecclesiasticide, I am still unsure.

* *

“Kindly do not snort, Russell.”

“I only snort at snort-worthy statements.”

All the world’s stage: places Russell goes in this Memoir

Britain: Sussex, London, Oxford, Cambridge

(See the

Maps chapter

for details.)

Laurie’s Remarks

The third volume of Memoir opens in the summer of 1923—but right away, the attentive reader is taken aback: isn’t there a gap of two and a half years between the final scene of

Monstrous Regiment

and the opening of

Letter of Mary

? Indeed. This is the first indication that there may be certain areas of her autobiography into which Miss Russell does not intend to venture, at least not for public consumption. Ten books later, the early months of her marriage to Sherlock Holmes have yet to be explored, other than in the speculation of her many readers. (See the Companion chapter, On Matters Unspoken.)

Instead, we find Russell deeply immersed in the part of her life that does not really involve Holmes: theological studies. Into their peaceful day drops a case (as so often their cases drop) with ties to the early days of their partnership. A woman who not only befriended them, but impressed them during their 1919 visit to Palestine comes back into their lives, and hands them an object. Miss Dorothy Ruskin then disappears, leaving them with a token of her appreciation.

A beautiful box, with a hidden center. It might as well have been a bomb.

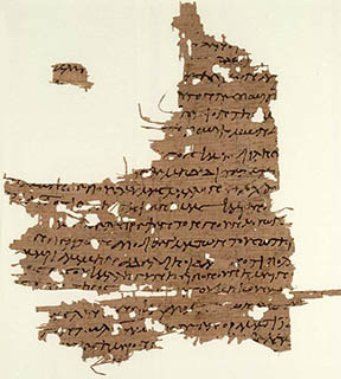

There is, in fact, a so-called “Gospel of Mary Magdalene,” a fragmentary dialogue between the risen Savior and the disciples, in which only Mary understands what Jesus is saying, and where it is up to her to comfort and lead the others. It is a speculative text from the early days of the Church, before the canonization of the New Testament and the establishment of the Creeds. What we have is a fifth-century papyrus copying what appears to be a second-century original.

Gospel of Mary Magdalene fragment

The “Magdalene’s Gospel” is controversial enough, although being a piece of Gnostic teaching (that is, based on esoteric Knowledge that divides the physical and spiritual worlds), it is easy enough to consign to the corners of Christian belief.

What Russell is given is on a whole other order of controversial. A piece of writing which, even if unprovable, could split the foundations of the Christian world.

And here Russell thought Dorothy Ruskin was a friend…

Excerpt

The envelope slapped down onto the desk ten inches from my much- abused eyes, instantly obscuring the black lines of Hebrew letters that had begun to quiver an hour before. With the shock of the sudden change, my vision stuttered, attempted a valiant rally, then slid into complete rebellion and would not focus at all.

I leant back in my chair with an ill-stifled groan, peeled my wire-rimmed spectacles from my ears and dropped them onto the stack of notes, and sat for a long minute with the heels of both hands pressed into my eye sockets. The person who had so unceremoniously delivered this grubby interruption moved off across the room, where I heard him sort a series of envelopes

chuk-chuk-chuk

into the wastepaper basket, then stepped into the front hallway to drop a heavy envelope onto the table there (Mrs Hudson’s monthly letter from her son in Australia, I noted, two days early) before coming back to take up a position beside my desk, one shoulder dug into the bookshelf, eyes gazing, no doubt, out the window at the Downs rolling down to the Channel. I replaced the heels of my hands with the backs of my fingers, cool against the hectic flesh, and addressed my husband.

“Do you know, Holmes, I had a great-uncle in Chicago whose promising medical career was cut short when he began to go blind over his books. It must be extremely frustrating to have one‘s future betrayed by a tiny web of optical muscles. Though he did go on to make a fortune selling eggs and trousers to the gold miners,” I added. “Whom is it from?”

“Shall I read it to you, Russell, so as to save your optic muscles for the

metheg

and your beloved furtive

patach

?” His solicitous words were spoilt by the sardonic, almost querulous edge to his voice. “Alas, I have become a mere secretary to my wife‘s ambitions.”

(For more background and a longer excerpt, see this book’s page on the Laurie R. King website.)

The Moor

Russellisms

Damn the man, he knew me far too well.

**

“It is a place that encourages fanciful thoughts,” he said indulgently.

**

Why was it, I reflected irritably, that Holmes’ little adventures never took us to luxury hotels in the south of France…

All the world’s stage: places Russell goes in this Memoir

England: Oxford, Devon, Dartmoor, Plymouth

(See the

Maps chapter

for details.)

Laurie’s Remarks

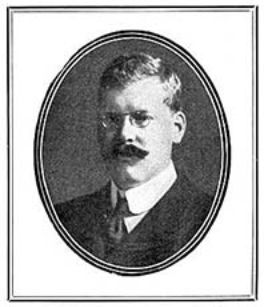

Shortly after returning home from the Boer War, Arthur Conan Doyle set off on a tour of Dartmoor with a friend he had made on the boat home from South Africa. Bertram Fletcher Robinson was a journalist and long-time resident of Devon, who told Doyle wild moorland tales, including one about a squire’s curse and a pack of devil dogs.

Bertram Fletcher Robinson

One wants to believe that Arthur Conan Doyle met Sabine Baring Gould when he went to Dartmoor. Certainly the squire of Lewtrenchard lived there in 1901, and there is no doubt he was known to everyone in the area. Still, one has to suspect that if Doyle had met Baring Gould, he would have been unable to resist using Lewtrenchard Manor, with its dining room walls (painted by a daughter of the house) emblazoned with the Virtues—including the robed Investigatio.