The Mary Russell Companion (18 page)

Read The Mary Russell Companion Online

Authors: Laurie R. King

Tags: #Mystery; Thriller & Suspense, #Mystery, #Women Sleuths, #Reference, #Writing; Research & Publishing Guides, #Research

Investigatio

The essay Laurie wrote for the Sabine Baring-Gould Appreciation Society can be found in her collection

Laurie R. King’s Sherlock Holmes

, but its essence is boiled down in the following paragraphs, comparing the Baring-Gould’s autobiography,

Early Reminiscences

, with the later Holmes “biography” penned by the vicar’s own grandson, W. S. Baring Gould,

Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street

:

From

Early Reminiscences

:

Sabine Baring-Gould was born on the 28

th

of January, 1834. “My father had been a cavalry lieutenant in the East Indian Company’s service—uniform blue and silver. He met with an accident: whilst driving a stout friend in his dog-cart, the vehicle was upset and the friend fell on him and dislocated his hip. He was not carefully treated, and was sent home invalided.” And later, “On 6 July, 1837, we left England in the steam vessel,

Leeds

, for Bordeaux….From Bayonne the whole party moved for the winter to Pau, where we took a flat on the Grande Place.”

In the summer of 1838, the Baring-Gould family moved on to Montpellier where, as young Sabine’s mother wrote, “We were not a little glad to find a delightfully snug and pretty little house…in the best part of the town” which had “a piece of water in the middle (very shallow) and railed around to the height of Sabine’s waist, full of gold fish, which serve to delight the little ones.”

“In October, 1840…we crossed to Rotterdam….We remained for some time at Cologne, as the weather was breaking up and winter setting in, so that it was not convenient for travelling.

“One drawback to going abroad had been the publication in numbers of

Nicholas Nickleby

, that was begun in 1839, and odd as it may seem, I think that really one reason for inducing my father to spend the winter at Cologne was that he might be more certain to obtain the issues of that story as they came out.”

From

Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street

:

Sherlock Holmes was born twenty-two days earlier and twenty years later, on 6 January, 1854, to “a young cavalry lieutenant in the services of the East India Company—uniform blue and gold—[who] had offered, one evening, to drive a friend home from the company mess. Perhaps the dinner had been an exceptionally good one. Certainly both the cavalry lieutenant and his friend were heavy men, each weighting in the neighborhood of fourteen stone. In any case, it followed that the dogcart shortly turned over. The friend fell upon his companion, the cavalry lieutenant. The friend was unhurt, but the hip of the cavalry lieutenant was dislocated, and he was invalided home without delay.”

When Sherlock was a year old, his father, the retired officer, “led his entire family aboard the steamship

Lerdo

on July 7, 1855. They were bound for Bordeaux, across the Bay of Biscay. From Bordeaux they traveled to Pau, and there they wintered, taking a flat in the Grande Palace.”

In May, 1858, the family removed to Montepellier, where “they took a snug and pretty little house in the best part of town…with a goldfish pool to delight Sherlock and his brothers.” (Note that Baring-Gould believed there was a third and eldest brother, “Sherrinford”—a name that appears in the Conan Doyle notes as a possible name for his character, later re-christened “Sherlock”.)

And “in October 1860 they crossed to Rotterdam. Two months later this wandering family, these genteel gypsies, pitched tent in Cologne. The Rhine in that winter of 1860-61 was frozen over, and the while family had several months of peace during with Siger Holmes [the father] continued his studies.”

Excerpt

The telegram in my hand read:

RUSSELL NEED YOU IN DEVONSHIRE. IF FREE TAKE EARLIEST TRAIN CORYTON. IF NOT FREE COME ANYWAY. BRING COMPASS.

HOLMES

To say I was irritated would be an understatement. We had only just pulled ourselves from the mire of a difficult and emotionally draining case and now, less than a month later, with my mind firmly turned to the work awaiting me in this, my spiritual home, Oxford, my husband and longtime partner Sherlock Holmes proposed with this peremptory telegram to haul me away into his world once more. With an effort, I gave my landlady’s housemaid a smile, told her there was no reply (Holmes had neglected to send the address for a response—no accident on his part), and shut the door. I refused to speculate on why he wanted me, what purpose a compass would serve, or indeed what he was doing in Devon at all, since when last I had heard he was setting off to look into an interesting little case of burglary from an impregnable vault in Berlin. I squelched all impulse to curiosity, and returned to my desk.

Two hours later the girl interrupted my reading again, with another flimsy envelope. This one read:

ALSO SIX INCH MAPS EXETER TAVISTOCK OKEHAMPTON, CLOSE YOUR BOOKS. LEAVE NOW.

HOLMES

Damn the man, he knew me far too well.

I found my heavy brass pocket compass in the back of a drawer. It had never been quite the same since being first cracked and then drenched in an aqueduct beneath Jerusalem some four years before, but it was an old friend and it seemed still to work reasonably well. I dropped it into a similarly well-travelled rucksack, packed on top of it a variety of clothing to cover the spectrum of possibilities that lay between arctic expedition and tiara-topped dinner with royalty (neither of which, admittedly, were beyond Holmes’ reach), added the book on Judaism in mediaeval Spain that I had been reading, and went out to buy the requested stack of highly detailed six-inch-to-the-mile Ordnance Survey maps of the southwestern portion of England.

At Coryton, in Devon, many hours later, I found the station deserted and dusk fast closing in. I stood there with my rucksack over my shoulder, boots on feet, and hair in cap, listening to the train chuff away towards the next minuscule stop. An elderly married couple had also got off here, climbed laboriously into the sagging farm cart that awaited them, and been driven away. I was alone. It was raining. It was cold.

There was a certain inevitability to the situation, I reflected, and dropped my rucksack to the ground to remove my gloves, my waterproof, and a warmer hat. Straightening up, I happened to turn slightly and noticed a small, light-coloured square tacked up to the post by which I had walked. Had I not turned, or had it been half an hour darker, I should have missed it entirely.

Russell,

it said on the front. Unfolded, it proved to be a torn-off scrap of paper on which I could just make out the words, in Holmes‘s writing:

Lew House is two miles north.

Do you know the words to “Onward Christian Soldiers” or “Widdecombe Fair”?

—H.

I dug back into the rucksack, this time for a torch. When I had confirmed that the words did indeed say what I had thought, I tucked the note away, excavated clear to the bottom of the rucksack for the compass to check which branch of the track fading into the murk was pointing north, and set out.

I hadn’t the faintest idea what he meant by that note. I had heard the two songs, one a thumping hymn and the other one of those overly precious folk songs, but I did not know their words other than one song’s decidedly ominous (to a Jew) introductory image of Christian soldiers marching behind their “cross of Jesus” and the other’s endless and drearily jolly chorus of “Uncle Tom Cobbley and all.” In the first place, when I took my infidel self into a Christian church it was not usually of the sort wherein such hymns were standard fare, and as for the second, well, thus far none of my friends had succumbed to the artsy allure of sandals, folk songs, and Morris dancing. I had not seen Holmes in nearly three weeks, and it did occur to me that perhaps in the interval my husband had lost his mind.

(

Laurie R. King’s Sherlock Holmes

is available as an ebook, through her website. For more background and a longer excerpt, see

this book’s page

on the

Laurie R. King website

.)

O Jerusalem

Russellisms

“But women do not fight.”

“This one does,” I answered.

**

“In all my years, I don’t believe I have ever before required the services of a midwife, Russell.”

**

Never, never will I understand men.

All the world’s stage: places Russell goes in this Memoir

Palestine (modern Israel): Javneh, Acra, the Sinai, Beersheva, Jerusalem, Dead Sea

(See the

Maps chapter

for details.)

Laurie’s Remarks

(

O Jerusalem

, which re-visits an episode described briefly in

The Beekeeper’s Apprentice

, also re-visits Russell and Holmes at an earlier stage in their relationship. This makes for an interesting flavor in the novel, since a reader familiar with the Memoirs knows more than the two people in question do…)

Memoirs, along with their fictional counterpart, historical novels, are appealing not because they tell us about the past. Yes, the information gained can be both entertaining and useful, but we read them not for information, but for knowledge. We read them because they tell us not only where we come from, but who we are today. They are mirrors—through a glass, darkly—that present us with another way of looking at ourselves and our world.

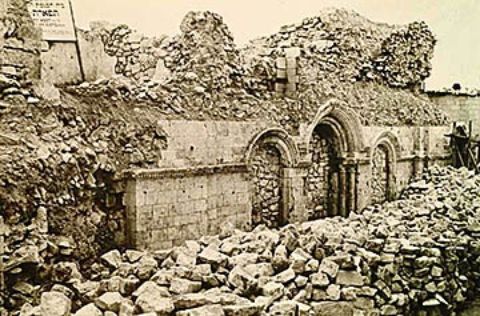

Take

O Jerusalem

. Few visitors to that holiest of cities would suspect the complexity of the world beneath their feet, those long-buried historical remnants and built-over alleyways, crypts, and cellars dating to Roman times, and before. Most visitors are aware of Jerusalem as a historical being, of course: why else come here? But the sheer size of its levels, the unseen worlds beneath hard paving stones: those take some work of the imagination.

The layers of Jerusalem

The Twentieth century, although close to the surface in the city’s historical layers, is one of the more tempestuous—not the early years, but the world went up in flames in 1914, and Palestine with it. When the Turks set themselves against the British in the Great War, their Palestine became the southernmost Front of the War.

In the autumn of 1917, the Great War that everyone had expected to be finished before its first Christmas was looking at a third holiday season. The Western Front was now 450 miles of mud and blood. Gallipoli had been a catastrophic failure, the Bolshevik revolution rendered Russia uncertain, and the Kaiser’s bombs were falling on central London.

Then in December, General Edmund Allenby electrified the British people with his Christmas gift: Jerusalem, wrenched from the Ottomans in a deft series of battles (of troops and of wits) that shook the foundations of the German ally. Britain’s conquering hero dusted off his boots and walked through the ancient city’s gate (where the Kaiser had driven), lending heart and determination to his countrymen in the cold north.