The Mascot (42 page)

Authors: Mark Kurzem

I nodded.

“This is the very spot where they filmed me,” he said, “playing blindman's bluff with the other children.”

My father pulled his brown case onto his lap. He clicked open the lock. This time there was no secretiveness, no holding the lid in a partly opened position so that nobody but himself could see inside. His hands fumbled in the morass of papers and photographs, and he drew out a tatty, yellowed scrap of paper. It was not even a full sheet, and its edges indicated that it had been roughly torn by hand.

“Look!” my father commanded, passing across the scrap.

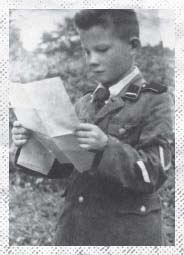

It was a newspaper article. I handled the fragile page gently: it seemed as though it might suddenly disintegrate. In the center of the sheet was an image I recognized. It was my father in uniform, reading a map.

When telling us stories as children, my father had held it up a number of times, as a prop to whatever he was recounting. But it had always remained firmly in his grip and only ever briefly revealed. This was the first opportunity I'd ever had to scrutinize the photo at some length, and I could now discern that he was actually in military uniform. It occurred to me how deftly he had always handled this pictureâhe had positioned his thumb or one of his fingers over any sign that would give away the truth about his uniform. I was unsettled by the effort he had made to keep the truth from our family.

A photo taken during the filming of the Latvian propaganda newsreel in which my father appeared in 1943.

“I am certain that this photo is a still taken on the day the film was made here,” he said.

“What newspaper is this from?” I asked.

“It's from the

Eagle

, a paper in Riga,” my father replied. “It was taken in 1943.”

My father looked around again. “Over there,” he said, pointing to a small clump of trees about twenty yards from us. “That's where it was taken.

“I recall some things from the day of filming,” he said reflectively. “Various people arrived throughout the afternoon. A group of kids about my age appeared on a bus. Later Lobe arrived with an entourage of officers who inspected the grounds of Carnikava.

“Lobe insisted to Auntie that I get back into my uniform. You see, Carnikava was the only place that I was willing to take off my uniform: in the summer I'd spend all day at the seashore and virtually lived in my swimming trunks.

“We were up at around dawn the next morning. I was still sleepy but Auntie dressed me in my uniform, smoothed my hair, and took me down to a room where a crew member was making the other children ready for the film.

“One group of girls were already dressed in folk costumes, and their hair had been plaited with colorful ribbons. They were being looked after by a lady in a white uniform who was giving them bowls of ice cream. At that hour! When she saw me, she came over and offered me a bowl as well. I couldn't believe it! I thought, âThis is going to be a great day.'

“Then another woman came up to me and began to straighten my uniform. I wriggled about, trying to enjoy my ice cream. âBe still!' she said impatiently. âDon't forget you are a soldier! We must make you handsome for the film.'

“Then she tried to apply makeup. I squirmed at that and screwed up my face. âSoldiers do not use this!' I stamped my foot. âIt's for ladies.'

“This only caused everybody in the room to laugh at me.

“âShush, you,' she said playfully, planting a kiss on my forehead. I could feel my face turn hot and red with outrage. âYou don't like my kisses?' she exclaimed. Fortunately for me, somebody interrupted us. They were ready to film me.

“Outside in the morning sunshine the crew was waiting with a camera. The girls rolled their eyes and began giggling when they saw me. Everything had been planned, down to the last detail. The director organized our positions around a maypole, telling us to join hands to rehearse our dance.”

“A maypole dance?” I laughed. I simply could not imagine my father dancing.

“I know,” he said, shaking his head in disbelief. “And those girls I had to dance with. They were real little Aryan maidens with terrible, fierce tempers.” My father screwed up his face as if he were being asked to dance with them this instant.

“One girl complained that she didn't want to be next to me: âthe little nuisance,' she called me. âI'm not holding hands with any of these awful girls,' I said arrogantly. That started the girls off again. âYou're not even a real Latvian!' one of them said to me.

“I pinched her”âmy father chuckled loudlyâ“and all hell broke loose. The commander gave me a harsh warning. I settled down quickly.

“After that, I can only recall bits and pieces, because the fun had gone. It was work and, with Commander Lobe hovering threateningly in the background, I just did what I was told.

“They filmed us eating lunch. The girls tormented me again, this time because I couldn't use a knife and fork properly. I showed them up later, though, when we had to change to our swimming trunks and play on the beach. I could run faster than any of them, and I was the only one who could do handstands.”

My father and I both laughed, but then his mood altered. “Imagine if we found the film,” he said pensively. Without another word, he rose and made his way down the steps. He walked directly toward a small copse that had been planted in a semicircle with the opening facing toward the house. Before he actually reached it, he stopped and nodded his head as if confirming something to himself. Then he headed to one particular tree. He beckoned me with a wave of his hand.

By the time I reached him he was crouched at the base of the tree and patting the grass all around him. “Help me up. I'm looking for treasure,” he said with disarming simplicity.

“Treasure,” I repeated. “What treasure?”

“Buried treasure that Uncle left behind when we fled Latvia.”

My father registered my look of disbelief. “No,” he protested, “I'm serious. It was in the summer of 1944. He and Auntie had taken me to Carnikava by car for the weekend. Uncle must have sensed that the writing was on the wall for Germany and Latvia, and he began to make plans for our departure.

“âThis might be our last visit here,' Uncle explained. âWe will have to leave many belongings behind. Collect a few of your things that will fit in your case.' That's the case I'm holding now. Uncle bought it for me in Riga.

“That first night in Carnikava I was asleep when something woke me. As I came to, I heard a noise coming from outside my bedroom window. I didn't know what to do. In truth, I'd gotten used to the good lifeâbeing safe from the elementsâand I thought it might be wolves. But as I sat there on the edge of my bed, I soon realized that it wasn't wolves; it was a digging sound.

“I went over to the window and peeked from behind the curtain. There was enough moonlight that I could just make out the garden. By these treesâliterally where we are standing nowâI could see two figures moving about. As my eyes got used to the darkness, I saw that it was Auntie and Uncle. Auntie was holding a small lamp close to Uncle, who was digging up the soil. I noticed that Uncle had two small sacks at his feet, which he then placed into the hole he'd created.

“I have no inkling as to why, but at that moment Uncle looked up at my window. I backed away quickly, but I was sure that he'd caught a glimpse of me. I pressed myself against the wall, worried because I knew that I'd just witnessed something that I shouldn't have. I crept back into bed and drew the covers up so that only my eyes and the top of my head were visible. I couldn't sleep. I lay there worried that Uncle would be fierce with me the next morning.

“Downstairs I heard the sound of a door closing and then footsteps as Auntie and Uncle made their way upstairs. They passed by my door, but moments later I heard one set of footsteps return and stop outside. I could tell that they were Uncle's. I held my breath, waiting for the handle to turn, but he seemed to think better of it and moved on.

“Early the next morning I woke with a start. There was a shadow over me. I let out an unholy scream and tried to spring out of bed. Whoever it was put his hand over my mouth and held me down on the bed. Then I saw that it was Uncle. He put one finger to his lips indicating that I should be quiet, and then he sat down on the edge of the bed. He spoke in a whisper, explaining what he and Auntie had been doing the night before: he had some gold and silver that he couldn't take with him.

“âYou must promise to keep it our secret,' he said solemnly. âIt's yours. If Auntie and I never return, it's yours. After all this mess is over, come back and get it.' Then he rose wearily from the bed. âGet dressed,' he said, âand go down for breakfast.'

“At the door he stopped and turned. âDon't forget,' he said. âIt's our secret.' With that he was gone.

“I think it's still here.” My father frowned intently at the ground. “Nothing seems to have been disturbed.”

“Uncle didn't come back for it?”

My father shook his head. “No, he never returned to Latvia. And he never once mentioned the hidden treasure to me again. Not even after we'd emigrated to Australia.”

“He must have told someone else about it,” I suggested. “And they've collected it.”

“Who would he tell?” my father responded as if my idea were absurd.

“His daughters or grandchildren, perhaps?”

“No.” My father shook his head vigorously. “We would've known about that, one way or another. The loot should still be here, below our feet.”

“What happens now?” I asked. “Do you want to look for it?”

“What, with our bare hands? Don't be stupid. Perhaps we'll come back another time,” my father added.

“When?”

My father tried to shrug me off. He began to walk away from me toward the hole in the fence we had climbed through.

“When are we going to get another chance to go back for it?” I called after him.

“Look,” he said, turning back to me. “I don't want their gold and silver. It's not mine.”

“Uncle said you should have it.”

“Leave well enough alone, son,” he replied irritably.

“Why don't you want it?” I persisted.

My father turned to face me. “Because that would mean they'd bought me,” he spat out, incensed. He looked at his watch. “If we don't hurry, we'll miss the train back to Riga.”

Without waiting for me, he strode to the gap in the fence and onto the unpaved road, where for one moment, he faltered. He seemed to be torn between continuing on his way and turning for one final glance at the house that had now taken on a malevolent presence: my father had been used as a propaganda toolâa little mascot for the Reich and its poisonous ambitions.

He did not turn around. Instead, together we began to retrace our steps back to the train station. He quickened his pace, as if in flight, now from Carnikava.

By the time we reached the station, my father's mood was calmer and more pensive.

“Who would have thought we'd find Carnikava again?” I ventured, hoping that he'd confide his feelings to me. “Greater chance of winning the lottery⦔

“Carnikava was no prize,” he snapped harshly at me.

I was shocked. I could tell that my father instantly regretted his tone with me.

“Too many memories there,” he said. “Memories and ghosts.”

“You don't believe in ghosts!” I joked, hoping to return him to a better mood.

“After seeing Carnikava I do,” he hit back. “The place is full of them.”

The train to Riga pulled in, and soon we were safely ensconced in a carriage, heading away from Carnikava. He would likely never see his refuge by the sea again. He seemed relieved.

THE FILM

I

n the months since his astonishing revelations in our kitchen, I had contacted various film archives in Russia, Germany, Latvia, and elsewhere. In my communications I'd described the bare details of the film that he had given me.

Nothing had come of the search. None of the organizations had had the film in their archives. At the time I'd kept it from him because I wanted to surprise him if I found it. I didn't want to get his hopes up unnecessarily.

The Latvia State Archive for Audiovisual Document was among those that had responded in the negative, but now that I was actually in Latvia I decided to approach it again. Having just been to Carnikava, I knew how meaningful it would be not just for my father but for all of us to see the film.

We returned to the hotel from Carnikava just before three and went our separate ways. My father was keen to return to his room and check on my mother. I went to my room and placed the call to the archive immediately. After a brief reminder, Miss Slavits, my contact there, recalled my unusual request. I described to her the new information I'd gotten from my father that day. I skirted around the issue of my father's SS uniform. I was still uncertain about the depth of Latvian nationalism, particularly in a government institution, and had no idea whether Miss Slavits would willingly locate a film if she knew its potential for controversy. My parents' experiences in Melbourne had taught me that some Latvians did not take kindly to my father's story. As it turned out, Miss Slavits was willing to assist me provided I could pay the archive for its time. She'd warned me that closing time was 5:00 p.m., and it was already well past three o'clock. We were due to leave Riga for London early the next morning, so this would be my only opportunity. I put on my jacket and left the hotel.

The taxi took me to the outskirts of the city, where it stopped outside a building. I hurriedly paid and made my way to the entrance. I cursed. It was a department store. Anxiously I hailed another taxi and frantically stabbed at the paper on which the address Miss Slavits had dictated to me was written.

“Yes, yes.” He took off wildly into the traffic.

I looked at my watch. It was now nearly four. I urged the driver to hurry. He floored the accelerator, and the car surged forward as if it were about to take off into the air.

Within minutes the taxi screeched to a dramatic stop outside a drab concrete building. A sign on the facade indicated that this was the archive. I sprinted up the steps that led to the entrance.

I quickly glanced again at my watch: 4:15. I tried the door but it was locked. I pushed my face flat against the glass and peered inside. At first glance, the dark, vast, cavernous space appeared to be deserted. However, as my eyes grew accustomed to the dim lighting, I could just make out a bulky silhouette at a desk. It stirred slightly, giving me a start.

I tried the door again. The creature inside did not react. I tapped on the glass.

I hammered on the glass with my fist, and the silhouette rose slowly from behind the desk and moved laboriously toward me. I could see now that the person was extremely squat, as wide as he or she was tall. This impression did not alter as the figure reached the other side of the glass barrier. Now I could see, however, that it was an elderly woman, dressed in a paramilitary uniform. It was her turn to push her face up against the glass pane and to scrutinize me with her filmy eyes.

“Miss Slavits,” I shouted, my face close to hers.

She showed no immediate sign of letting me in. Her eyes sharpened as she appraised me. After several moments she seemed satisfied and opened the door. She began to shuffle slowly back to her desk, indicating that I should follow her, which I did. The guard eased herself back into her chair.

“Miss Slavits,” I repeated.

Without even the slightest glance in my direction, she thrust the visitors' book and pen under my nose. After a bored, cursory glance at my signature and without looking up, she pointed her finger at a door on the far side of the room. I entered a darkened corridor, where I was greeted by a captivating young woman.

“Mr. Kurzem?” she said. Miss Slavits's English was gentle and melodic. “My office is this way.”

We made our way through a maze of dark corridors. As we did so, Miss Slavits told me about three reels of film she'd unearthed since we spoke. “They were in a dust-covered shoe box at the back of a filing cabinet,” she explained, slightly embarrassed. “They may have been there for decades. I'm sorry that I did not find them earlier. I haven't seen them yet, and there is no description of the contents except for the words âLatvian countryside.' That could mean anything, but it may be worth looking.” She gave me a sympathetic smile.

“Can we view the footage now?” I asked. In truth I didn't hold out much hope that I would find my father's film. I imagined that much of Latvia's infrastructure had been destroyed by the Nazis as they retreated.

“Certainly,” she replied and led me to a neighboring viewing room.

It took several seconds for my eyes to adjust to the brightness of the fluorescent lights. We both donned bright pink dust coats in a limp gesture toward film preservation and sat down before an archaic Steenbeck footage machine.

“I should warn you that the condition of the films may be very poor,” she said, gingerly removing the first reel from the box.

She gently loaded the spool onto the machine and began to pump a pedal so that the film jerked along frame by frame. For a moment I stared at a blank screen before black-and-white images appeared. The reel's quality had deteriorated considerably, so that I could barely make out the images of soldiers marching across a field. The commentary in German, which seemed to be describing the experiences of German soldiers in Latvia, was largely drowned out by the crackle of static.

Miss Slavits let the reel run to its end to be certain. I shook my head. “The next one?” Miss Slavits asked. I nodded.

The second reel, too, contained images of German soldiers on patrol in the Latvian countryside. I watched it through to the end. By then a cloud of disappointment had descended upon me. I sat in silence as Miss Slavits loaded the final reel.

The first images that appeared on screen seemed to be much the same as those on the previous reelsâGerman soldiers marching. I didn't see the point of sitting through more of the same thing. Filled with gloom, I rose and, without waiting for Miss Slavits to turn off the machine, began to remove my dust coat. At that precise moment, with my back to the screen, I heard the words of the German narrator: “And now we are outside Riga.” I spun around to face the screen and snapped at Miss Slavits to let the reel continue. She was taken aback but managed to reverse the footage several frames to where the commentary had begun.

This time I saw the images that had accompanied the words. There was Carnikava, shot from its front gate, where my father and I had stood only hours before. It was in much better condition and bathed in sunshine, not a bit ominous.

As the German narration continued, accompanied by happy children's music in the background, the camera cut to a close-up of the steps leading up to the front door. As the voice began to describe the presence of a young soldier at Carnikava, the doors to the house burst open and a throng of children dashed down the steps and into the sunshine. Among them was a boy, no more than eight or nine years old, in uniform. My breath stopped for an instant. I recognized his face immediately. It was my father. He bore a remarkable resemblance to my nephew James: an identical smile and a double cowlick of hair framing his face.

“It's himâ¦my father,” I said in a hoarse tone.

Miss Slavits stopped the projector. “You must sit down,” she said, giving me a concerned look.

“I'm fine,” I protested, taking a deep breath and easing myself back into my chair. “I don't want to see any more. My father should see it first. Can I bring him?”

“Now?”

“Of course.”

“We are closing very soon,” she said, looking at her watch. “I'm sorry. Tomorrow?”

“We're leaving first thing in the morning,” I explained. “Back to London.”

Miss Slavits was silent for a moment. Then she spoke. “From what I have just seen,” she said slowly, “your father was a very special boy.”

I was unsure of the inflection in her voice, so I shrugged. “My father can come now?” I asked in a bewildered voice, pushing my case.

Miss Slavits considered my request for several moments. Then she nodded her head sympathetically.

“Can I use your telephone?”

“From my office,” she answered. “This way, please.”

The telephone rang in my parents' hotel room. Before I had even begun to explain, my father started in on me. “I've been knocking on your door for the last hour. We've been worried sick,” he said, alarmed. “Where are you?”

I cut him off. “Can Mum hold the fort there?”

“What's up?”

“Listen! I want you to write down this address and get here as soon as you can.”

“I'm just relaxing with a cup of teaâ” my father started to grumble.

“Don't argue, Dad,” I said irritably.

“First tell me what's going on,” he said.

I ignored his demand. “Get a taxi!” I insisted.

“I'm on my way,” he said. The line clicked as my father hung up.

I turned to Miss Slavits. “My father will be here very soon,” I promised her.

I waited in the dark entrance hall. My footsteps echoed as I paced back and forth near the glass doors. About twenty minutes later a taxi swung into the driveway. I watched as my father got out of the car looking disoriented. As he moved toward the entrance he noticed me on the other side of the glass door. I held it open for him.

“Where are we? Stalin's tomb?” he joked.

“Just follow me, Dad.” I led my father to the projection room where Miss Slavits was waiting for us. I introduced them.

“You must be very excited,” Miss Slavits said, unaware that I'd revealed nothing to my father. Suddenly it dawned on him. “You've found the film?” he exclaimed, his eyes bright with excitement.

Before I could respond, Miss Slavits cut in. “One moment. You must wear a jacket,” she remembered, going to the closet. When Miss Slavits reappeared with another pink dust coat, I led my father over to the projector and positioned his chair directly in front of the screen. With a nod I indicated that she should restart the machine.

I could just make out my father's features in the glare of the screen. He was spellbound. I turned my attention back to the footage and watched my father march across the lawn in front of the holiday house with the other children following behindâa Jewish boy-soldier with a group of Aryan children under his commandâas the narrator's voice barks out in German the story of the “boy in uniform,” “the child found by the Latvian SS legion who rescued him from the dangers of the front.”

Then the footage jumps abruptly to a new scene. My father is now blindfolded and surrounded by the other children: the stooge in a game of blindman's bluff. The boy is spun around and around and then left staggering and groping as he tries to catch the perpetrators. And then I noticed something even more unnervingâon the perimeter of the circle of children, I momentarily caught sight of Jekabs Dzenis smiling benignly at them.

The scene shifts to the seaside, where all the bright, happy Aryan children in their swimming costumes frolic on the beach as if in some Germanic naturist ritual. Among them is my father, bare-chested like the others, doing handstands on the sand. The screen gives another hiccup and reveals an image of the children at dinnertime. The camera focuses on my father, who struggles to use his knife and fork properly. But the camera does not linger there for very long: soon it is bedtime, and as lullaby music plays in the background, the face of a sleepy kitten appears on-screen. A nurse then appears and tucks in the sleepy little children. The narrator informs us that all is well in the world for them.

The footage ended abruptly, and the screen went blank. “That is all. Just over two minutes of footage,” I heard Miss Slavits say.

I continued to stare ahead, relieved that she'd not yet turned on the lights. What had just been revealed to me seemed somehow too intimate, and I was reluctant to engage with my father. Then I heard Miss Slavits ask him if he wanted to view it again. Out of the corner of my eye I saw my father nod his head vigorously.