The New Empire of Debt: The Rise and Fall of an Epic Financial Bubble (46 page)

Read The New Empire of Debt: The Rise and Fall of an Epic Financial Bubble Online

Authors: Addison Wiggin,William Bonner,Agora

Tags: #Business & Money, #Economics, #Economic Conditions, #Finance, #Investing, #Professional & Technical, #Accounting & Finance

Just a few months before, investors reached for the highest yields they could get. Now, they folded their arms, clutching to their breasts the lowest-yielding paper on the planet. Once they believed in capitalism and its bonds. Now, they wanted nothing that did not have the seal of the U.S. government on it. At the debut of 2007, they saw no danger. By the close of 2008, they saw nothing else.

In an earlier book,

Financial Reckoning Day

, written in 2002, we suggested that America was following in Japan’s footsteps. But instead of beginning a Japan-style correction, the U.S. economy took off in an American-style bubble.

In 2007-2008, the bubble popped.What now? Want to know? Just look at Japan!

Richard C. Koo’s argument is not far from the one we made seven years ago. In the 1980s, Japan ran up stock and property prices in a spree of debt and leverage. Then, when the bubble popped, the usual monetary stimulus didn’t work. The Bank of Japan cut rates to almost zero . . . still, few people were willing to borrow. Companies, banks, and individuals had to pay down the debt that they had accumulated in the boom; they did not want to borrow more money, even at zero interest rates. For seven years, from 1998 to 2005, net business borrowing went negative—meaning, businesses were paying off more debt than they were taking on.

The economy did not recover; instead, it got worse and worse. By 2005, stocks had lost 72 percent of their value, land was down 81 percent, and golf course memberships had sunk 95 percent from their peak.

This came as a shock to modern economists. Japanese officials were flummoxed. Of course, Japan tried to fight the downturn. They tried fiscal stimulus (government spending) and monetary stimulus (central bank policies). They ran deficits of 6 percent of GDP—equivalent to about a trillion dollar deficit in the United States. And they took interest rates down to near zero and left them there for years.What else could they do? U.S. economists accused them of not acting swiftly enough . . . or not having the stomach to let the big banks fail. But almost no one seemed to understand what was really going on. They should have. Irving Fisher described it back in 1933, observing that when people who are deeply in debt get into trouble, they usually sell assets. He called it a “stampede to liquidity.” Investors dump stocks and property for any price they can get—desperate to pay off their debts before they are dragged into bankruptcy.

2

This is the phenomenon known to economists as the “fallacy of composition.” What is good for every individual investor—cutting expenses, paying off debt—turns out to be bad for the economy as a whole. Because as each man pulls back, he takes something away from the other fellows around him. He pulls his money out of a stock; the price falls and the other shareholders are poorer. He walks to work rather than taking a taxi, and then the taxi driver has less income. He tells his son: “If you want a pizza, you have to get on your bicycle and go pick it up yourself . . . and get the cheapest one.” And then, the pizza-delivery service has less money. One man’s cost-cutting affects another man’s income. Revenues fall.Asset prices fall. Sales fall. Unemployment rises.The slump deepens.

In Japan’s case, combined capital losses from land and stocks grew from 1990 until 2002, at which time they reached $15 trillion—or three years worth of Japan’s GDP.

What would happen if the United States followed the same course? You can do the math yourself, dear reader. America’s GDP is about $14 trillion. Multiply that times three and you get $42 trillion. By the beginning of 2009, the United States had lost only about $4 trillion or $5 trillion in housing prices . . . and maybe another $6 trillion in stocks, for a total of about $11 trillion, maximum. A long way to go.

But there are two crucial differences between Japan and the United States. First, Japan had a healthier economy, with a positive trade balance, and huge savings. Second, the United States has the world’s reserve currency. These differences in initial conditions will make a huge difference in the outcome.

Japan could easily spend 6 percent of its GDP trying to replace private spending with government spending.The Japanese saved 19 percent of GDP. The government could simply borrow from its own people—like the United States did to finance World War II. But America can’t finance huge deficits internally; it doesn’t have the money. Its people don’t save enough. They haven’t enough savings to lend their government. Any money the government gets from Americans will have to come out of current private spending or out of other investments. Obviously, this is not going to do much good, since there is no net increase in spending or investing. Nor can the U.S. government expect to bring in unlimited financing from foreign sources. The foreigners save, but they need their money to rescue their own economies. What’s worse, the more the U.S. government has to compete for funds with other borrowers, the more interest rates will go up—worsening the picture for the economy as a whole.

The other point is vitally important, too. Not only did Japan have a cushion of cash to comfortably sit out the correction, it had no reason to do otherwise. With money in the bank, the Japanese were never threatened by an economic breakdown. And what money they owed, they owed to themselves.

America has neither of those two comforts. Millions live paycheck to paycheck, depending on credit cards to fill in the gaps. When unemployment rises above 10 percent—maybe above 15 percent—they will howl so loud the government will be forced to take desperate measures, which could send the deficit to $3 trillion. Then, crushed under the weight of so much debt, it won’t be long before the feds realize that we don’t “owe it to ourselves.” Instead, we owe trillions to foreigners. Foreign central banks alone hold about $2.4 trillion worth of U.S. government debt. About $10 trillion is said to be the total of all dollar-based obligations in foreign hands. That is a burden that could be easily lightened . . . if, for example, the dollar weren’t worth quite so much.

The United States is an empire of debt. Japan was a republic of credit. The Japanese never stopped saving. They never stopped making things. If they had a fault, it was the same fault that the Chinese have now—they made too much. While Americans underinvested in productive capacity, the Japanese overinvested. They had so much capacity, the world’s consumers could not keep up with it.

The United States is a very different story. We have elaborated it in this book—the story of an empire of self-delusion and flattery. America can have a soft, slow slump, but not a long hard one. It can’t afford it.

Let us imagine for a moment that the U.S. stock market did fall as much as Japan’s—not just the Nasdaq, which has tracked the Nikkei Dow rather closely—but all U.S. stocks. At its peak in 1989, the Nikkei was at 38,915.87. On January 1, 2009, the index stood at a little over 9,000—a loss of nearly 75 percent. And imagine that residential real estate were to fall in the United States as it did in Japan: After 1989, Japanese house prices dropped for 13 years. And imagine that consumers would stop shopping as they did in Japan and that prices would fall for nearly 10 years in a row. To put that last item in perspective, remember that consumer spending is 71 percent of the U.S. economy; in Japan it was never more than 55 percent. Now, ask yourself . . . how many U.S. households would still be solvent (see

Figure 14.1

)?

But people who have expected something for nothing for so long do not go gently into that good night. They rant and rail against the failing of the light—and demand action from their imperial representatives. “We want inflation,” they will say. “We will not be crucified on a cross of strong paper dollars,” they will add, as a theatrical flourish.

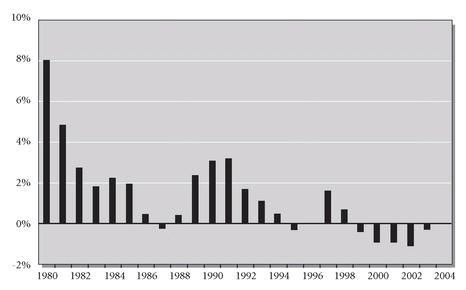

Figure 14.1

Japanese Inflation Rate, 1980-2004

After the Japanese stock market bubble burst in 1989, consumers stopped spending and prices fell for 10 years. Imagine what would happen if a collapsing credit bubble set in motion a similar trend in the United States. Consumer spending is now 71 percent of the U.S. economy; in Japan it was never more than 55 percent. How many U.S. households would remain solvent?

Source:

Statistics Bureau ( Japan).

Inflation would be an obvious way of reducing the value of America’s debts.This is how Germany reduced her debts after World War I.The Reich was left with a bill for $33 billion in reparations to be paid to the Entente powers. But Germany was worn out by the war and had no way of making such large payments. Out of desperation, she resorted to the printing press.

A 50 percent fall in the value of the dollar would wipe out half the real value of the U.S. debt—an amount greater than the entire dollar currency reserve holdings of all Asian central banks put together.

At some point, America’s debts will probably be incinerated by inflation. When the howls from consumers and voters grow loud enough, the Feds will panic. In desperation, Ben “Printing Press” Bernanke will point south, toward Zimbabwe or Argentina. “There . . . that is our only way out,” he will say.

15

The Mighty Fallen

The merde began hitting the fan in the summer of 2007.

“We are seeing things that were 25-standard deviation events, several days in a row,” said David Viniar, CFO of the smartest financial firm in the world, Goldman Sachs.

1

According to Goldman’s mathematical models, August, Year of Our Lord 2007, was a very special month. Things happened in that month that were only supposed to happen about once in a blue moon.

Either that, or Goldman’s models were wrong.

We recall looking out our window. Outside, we saw a summer day much like any other. And inside, what we saw in the news was also rather typical—a credit crunch. No, credit crunches don’t come along every day, but nor do 100,000 years separate one from another. In recent history there was the crash of the dot-coms, the crash of Long Term Capital in ’98, and the crash of ’87; outside of the United States, there have been a number of credit crunches, in Japan, Russia, Mexico, and various Asian countries.

When you make loans to people who can’t pay the money back, trouble is only a couple of standard deviations away. During the first eight months of 2007, some 1.7 million houses were caught up in foreclosure proceedings in the United States.That was just the beginning. At that stage, the amounts of money weren’t very large, not by Wall Street standards. But when the money didn’t show up, it had an alarming effect. Citigroup said it was $13 billion short. Morgan Stanley was said to be facing $8 billion in losses. Merrill Lynch set records with estimated losses of $18 billion.The cat still had Goldman Sachs’s tongue.

Already heads had begun to roll. First, Warren Spector of Bear Stearns got axed. Then, it was Peter Wuffli at UBS. He was followed by Stan O’Neal of Merrill Lynch. O’Neal made the headlines when he was pushed out of the corporate jet with a “golden parachute” valued at $160 million. After O’Neal hit the ground, Charles Prince of Citigroup, America’s largest bank, was chucked out.

What went wrong? The business model seemed so pure and simple. You simply bought up subprime loans from the knaves who made them, and then you cut them up, slicing and dicing them into a kind of mortgage spam.You got the rating agencies to bless them . . . and then you sold them off to naïve investors.The idea was to earn huge fees up front, while laying the risk onto the fools who bought the stuff.

When the going was good, it looked as though no business could be better. You were providing a valuable public service, helping people buy houses they couldn’t afford by redistributing the risk from the people who incurred it to people who had no idea it was there. And in the process, you earned such large fees you would get your picture in the paper, build a huge mansion in Greenwich, Connecticut, and acquire some abominable, but very expensive, paintings to put on the walls.What could go wrong?

Everything. The

Financial Times

provided more detail on what happened at Citigroup:

The bank reported that, at the end of September, it had around $2.7 billion of unsold collateralised debt obligations—pools of debt securities that are repackaged and distributed to other investors.

But it also had $4.2 billion of subprime loans it had bought in the past six months, and about $4.8 billion of loans to customers which were secured by subprime collateral. In addition, the bank had $43 billion of exposure to the most highly rated tranches of CDOs based on subprime mortgage assets.

2

It turned out Citi was fool and knave at the same time. It sold dubious subprime debt to its customers. But it bought it, too, and took it as collateral.

Gary Crittenden, Citi’s chief financial officer, claimed that the firm was simply a victim of unforeseen events.The losses were “driven by some events that have happened during the month of October,” he said, referring to downgrades by rating agencies. No mention was made of the previous five years, when Citi was busily consolidating mortgage debt from people who weren’t going to repay—pronouncing it “investment grade,” mongering it to its clients and stuffing it into its own portfolio—while paying itself billions in fees and bonuses. No, according to the masters of the universe, downgrades by Moody’s and Fitch’s were completely unexpected, like the eruption of Vesuvius; even the gods were caught off guard. Apparently, as of September 30, Citigroup’s subprime portfolio was worth every penny of the $55 billion Citi’s models said it was worth. Then, the moon turned blue.