The New Penguin History of the World (11 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

The peoples who are the actors of early history in the Near East all belonged to the light-skinned human family (sometimes confusingly termed Caucasian) which is one of the three major ethnic classifications of the species

Homo sapiens

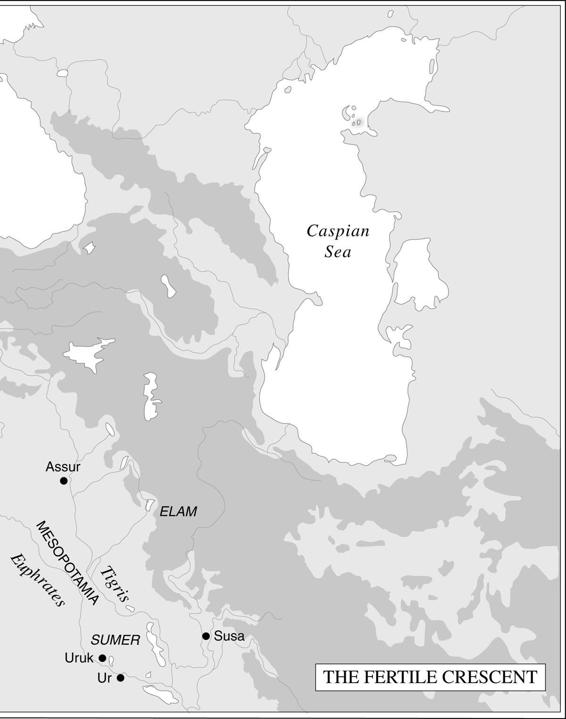

(the others being Negroid and Mongoloid). Linguistic differences have led to other attempts to distinguish them. All the peoples in the Fertile Crescent of early civilized times have been assigned on philological gounds either to ‘Hamitic’ stocks who evolved in Africa north and north-east of the Sahara, to ‘Semitic’ language speakers of the Arabian peninsula, to peoples of ‘Indo-European’ language who, from southern Russia, had spread also by 4000

BC

into Europe and Iran, or to the true ‘Caucasians’ of Georgia. These have been identified as the

dramatis personae

of early Near Eastern history. Their historic centres all lay around the zone in which agriculture and civilization appear at an early date. The wealth of so well-settled an area must have attracted peripheral peoples.

By about 4000

BC

most of the Fertile Crescent was occupied and we can begin there to attempt a summary of the next three thousand years which will provide a framework for the earlier civilizations. Probably Semitic peoples had already begun to penetrate it by then; their pressure grew until by the middle of the third millennium

BC

(long after the appearance of civilization) they would be well established in central Mesopotamia, across the middle sections of the Tigris and Euphrates. The interplay and rivalry of the Semitic peoples with the Caucasians, who were able to hang on to the higher lands which enclosed Mesopotamia from the north-east, is one continuing theme some scholars have discerned in the early history of the area. By 2000

BC

the peoples whose languages were of the Indo-European group have also entered on the scene, and from two directions. One of these peoples, the Hittites, pushed into Anatolia from Europe, while their advance was matched from the east by that of the Iranians.

Between 2000

BC

and 1500

BC

branches of these sub-units dispute and mingle with the Semitic and Caucasian peoples in the Crescent itself, while the contacts of the Hamites and Semites lie behind much of the political history of old Egypt. This scenario is, of course, highly impressionistic. Its value is only that it helps to indicate the basic dynamism and rhythms of the history of the ancient Near East. Much of its detail is still highly uncertain (as will appear) and little can be said about what maintained this fluidity. None the less, whatever its cause, this wandering of peoples was the background against which the first civilization appeared and prospered.

2

Ancient Mesopotamia

The best case for the first appearance of something which is recognizably civilization has been made for the southern part of Mesopotamia, the 700-mile-long land formed by the two river valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates. This end of the Fertile Crescent was thickly studded with farming villages in Neolithic times. Some of the oldest settlements of all seem to have been in the extreme south where deposits from centuries of drainage from up-country and annual floodings had built up a soil of great richness. It must always have been much easier to grow crops there than elsewhere, provided that the water supply could be made continuously and safely available; this was possible, for though rain was slight and irregular, the river bed was often above the level of the surrounding plain. A calculation has been made that in about 2500

BC

the yield of grain in southern Mesopotamia compared favourably with that of the best Canadian wheat-fields today. Here, at an early date, was the possibility of growing more than was needed for daily consumption, the surplus indispensable to the appearance of town life. Furthermore, fish could be taken from the nearby sea.

Such a setting was a challenge, as well as an opportunity. The Tigris and Euphrates could suddenly and violently change their beds: the marshy, low-lying land of the delta had to be raised above flood level by banking and ditching and canals had to be built to carry water away. Thousands of years later, techniques could still be seen in use in Mesopotamia, which were probably those first employed long ago to form the platforms of reed and mud on which were built the first homesteads of the area. These patches of cultivation would be grouped where the soil was richest. The drains and irrigation channels they needed could be managed properly only if they were managed collectively. No doubt the social organization of reclamation was another result. However it happened, the seemingly unprecedented achievement of making land from watery marsh must have been the forcing house of a new complexity in the way men lived together.

As the population rose, more land was taken to grow food. Sooner or later men of different villages would have come face to face with others

intent on reclaiming marsh which had previously separated them from one another. Different irrigation needs may even have brought them into contact before this. There was a choice: to fight or to cooperate. Each meant further collective organization and a new agglomeration of power. Somewhere along this path it made sense for men to band together in bigger units than hitherto for self-protection or management of the environment. One physical result is the town, mud-walled at first to keep out floods and enemies, raised above the waters on a platform. It was logical for the local deity’s shrine to be the place chosen: he stood behind the community’s authority. It would be exercised by his chief priest, who became the ruler of a little theocracy competing with others.

Something like this – we cannot know what – may explain the difference between southern Mesopotamia in the third and fourth millennia

BC

and the other zones of Neolithic culture with which it had already been long in contact. The evidence of pottery and characteristic shrines shows that there were links between Mesopotamia and the Neolithic cultures of Anatolia, Assyria and Iran. They all had much in common. But only in one relatively small area did a pattern of village life common to much of the Near East begin to grow faster and harden into something else. From that background emerges the first true urbanism, that of Sumer, and the first observable civilization.

Sumer is an ancient name for southern Mesopotamia, which then extended about a hundred miles less to the south than the present coast. The people who lived there may have been Caucasians, unlike their Semitic neighbours to the south-west and like their northern neighbours, the Elamites, who lived on the other side of the Tigris. Scholars are still divided about when the Sumerians – that is, those who spoke the language later called Sumerian – arrived in the area: they may have been there since about 4000

BC

. But since we know the population of civilized Sumer to be a mixture of races, perhaps including the earlier inhabitants of the region, with a culture which mixed foreign and local elements, it does not much matter.

Sumerian civilization had deep roots. The people had long shared a way of life not very different from that of their neighbours. They lived in villages and had a few important cult centres which were continuously occupied. One of these, at a place called Eridu, probably originated in about 5000

BC

. It grew steadily well into historic times and by the middle of the fourth millennium there was a temple there which some have thought to have provided the original model for Mesopotamian monumental architecture, though nothing is now left of it but the platform on which it rested. Such cult centres began by serving those who lived near them. They were not

true cities, but places of devotion and pilgrimage. They may have had no considerable resident populations, but they were usually the centres around which cities later crystallized and this helps to explain the close relationship religion and government always had in ancient Mesopotamia. Well before 3000

BC

some such sites had very big temples indeed; at Uruk (which is called Erech in the Bible) there was an especially splendid one, with elaborate decoration and impressive pillars of mud brick, eight feet in diameter.

Pottery is among the most important evidence linking pre-civilized Mesopotamia with historic times. It provides one of the first clues that something culturally important is going forward which is qualitatively different from the evolutions of the Neolithic. The so-called Uruk pots (the name is derived from the site where they were found) are often duller, less exciting than earlier ones. They are, in fact, mass-produced, made in standard form on a wheel (which first appears in this role). The implication of this is strong that when they came to be produced there already existed a population of specialized craftsmen; it must have been maintained by an agriculture sufficiently rich to produce a surplus exchanged for their creations. It is with this change that the story of Sumerian civilization can conveniently be begun.

It lasts about thirteen hundred years (roughly from 3300 to 2000

BC

), which is about as much time as separates us from the age of Charlemagne. At the beginning comes the invention of writing, possibly the only invention of comparable importance to the invention of agriculture before the age of steam. Most of it was done on clay for nearly half the time mankind has possessed the skill. Writing had in fact been preceded by the invention of cylinder seals, on which little pictures were incised to be rolled on to clay; pottery may have degenerated, but these seals were one of the great Mesopotamian artistic achievements. The earliest writings followed in the form of pictograms or simplified pictures (a step towards non-representative communication), on clay tablets usually baked after they had been inscribed with a reed stalk. The earliest are in Sumerian and it can be seen that they are memoranda, lists of goods, receipts; their emphasis is economic and they cannot be read as continuous prose. The writing on these early notebooks and ledgers evolved slowly towards cuneiform, a way of arranging impressions stamped on clay by the wedge-like section of a chopped-off reed. With this the break with the pictogram form is complete. Signs and groups of signs come at this stage to stand for phonetic and possibly syllabic elements and are all made up of combinations of the same basic wedge shape. It was more flexible as a form of communication by signs than anything used hitherto and Sumer reached it soon after 3000

BC

.

A fair amount is therefore known about the Sumerian language. A few of its words have survived to this day; one of them is the original form of the word ‘alcohol’ (and the first recipe for beer), which is suggestive. But the language’s greatest interest is its appearance in written forms at all. Literacy must have been both unsettling and stabilizing. On the one hand it offered huge new possibilities of communicating; on the other it stabilized practice because the consultation of a record as well as oral tradition became possible. It made much easier the complex operations of irrigating lands, harvesting and storing crops, which were fundamental to a growing society. Writing made for more efficient exploitation of resources. It also immensely strengthened government and emphasized its links with the priestly castes who at first monopolized literacy. Interestingly, one of the earliest uses of seals appears to be connected with this, since they were used somehow to certify the size of crops at their receipt in the temple. Perhaps they record at first the operations of an economy of centralized redistribution, where men brought their due produce to the temple and received there the food or materials they themselves needed.

Besides such records, the invention of writing opens more of the past to the historian in another way. He can at last begin to deal in hard currency when talking about mentality. This is because writing preserves literature. The oldest story in the world is the

Epic of Gilgamesh

. Its most complete version, it is true, goes back only to the seventh century

BC

, but the tale itself appears in Sumerian times and is known to have been written down soon after 2000

BC

. Gilgamesh was a real person, ruling at Uruk. He became also the first individual and hero in world literature, appearing in other poems, too. His is the first name which must appear in this book. To a modern reader the most striking part of the Epic may be the coming of a great flood which obliterates mankind except for a favoured family who survive by building an ark; from them springs a new race to people the world after the flood has subsided. This was not part of the Epic’s oldest versions, but came from a separate poem telling a story which turns up in many Near-Eastern forms, though its incorporation is easily understandable. Lower Mesopotamia must always have had much trouble with flooding, which would undoubtedly put a heavy strain on the fragile system of irrigation on which its prosperity depended. Floods were the type, perhaps, of general disaster, and must have helped to foster the pessimistic fatalism which some scholars have seen as the key to Sumerian religion.

This sombre mood dominates the Epic. Gilgamesh does great things in his restless search to assert himself against the iron laws of the gods which ensure human failure, but they triumph in the end. Gilgamesh, too, must die.