The New Penguin History of the World (42 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

Both his conquests and their organization in empire bear the stamp of individual genius; the word is not too strong, for achievement on this scale is more than the fruit of good fortune, favourable historical circumstance or blind determinism. Alexander was a creative mind and something of a visionary even if self-absorbed and obsessed with his pursuit of glory. With great intelligence he combined almost reckless courage; he believed his mother’s ancestor to be Homer’s Achilles and strove to emulate the hero. He was ambitious as much to prove himself in men’s eyes – or perhaps those of his forceful and repellent mother – as to win new lands. The idea of the Hellenic crusade against Persia undoubtedly had reality for him, but he was also, for all his admiration of the Greek culture of which he had learnt from his tutor Aristotle, too egocentric to be a missionary, and his cosmopolitanism was grounded in an appreciation of realities. His empire had to be run by Persians as well as Macedonians. Alexander himself married first a Bactrian and then a Persian princess, and accepted – unfittingly, thought some of his companions – the homage which the East rendered to rulers it thought to be godlike. He was also at times rash and impulsive; it was his soldiers who finally made him turn back at the Indus, and the ruler of Macedon had no business to plunge into battle with no attention for what would happen to the monarchy if he should die without a successor. Worse still, he killed a friend in a drunken brawl and he may have arranged his father’s murder.

Alexander lived too short a time either to ensure the unity of his empire in the future or to prove to posterity that even he could not have held it together for long. What he did in this time is indubitably impressive. The foundation of twenty-five ‘cities’ is by itself a considerable matter, even if some of them were only spruced-up strongpoints; they were keys to the

Asian land routes. The integration of east and west in their government was still more difficult, but Alexander took it a long way in ten years. Of course, he had little choice; there were not enough Greeks and Macedonians to conquer and govern the huge empire. From the first he ruled through Persian officials in the conquered areas and after coming back from India he began the reorganization of the army in mixed regiments of Macedonians and Persians. His adoption of Persian dress and his attempt to exact prostration – an obligatory kow-tow like that which so many Europeans in recent times found degrading when it was asked for by Chinese rulers – from his compatriots as well as from Persians, also antagonized his followers, for they revealed his taste for oriental manners. There were plots and mutinies; they were not successful, and his relatively mild reprisals do not suggest that the situation was ever very dangerous for Alexander. The crisis was followed by his most spectacular gesture of cultural integration when, taking Darius’s daughter as a wife (in addition to his Bactrian princess, Roxana), he then officiated at the mass wedding of 9000 of his soldiers to eastern women. This was the famous ‘marriage of East and West’, an act of state rather than of idealism, for the new empire had to be cemented together if it was to survive.

What the empire really meant in cultural interplay is more difficult to assess. There was certainly a wider physical dispersal of Greeks. But the results of this were only to appear after Alexander’s death, when the formal framework of empire collapsed and yet the cultural fact of a Hellenistic world emerged from it. We do not in fact know very much about life in Alexander’s empire and it must be unlikely, given its brief duration, the limitations of ancient government and a lack of will to embark upon fundamental change, that most of its inhabitants found things very different in 323

BC

from what they had known ten years before.

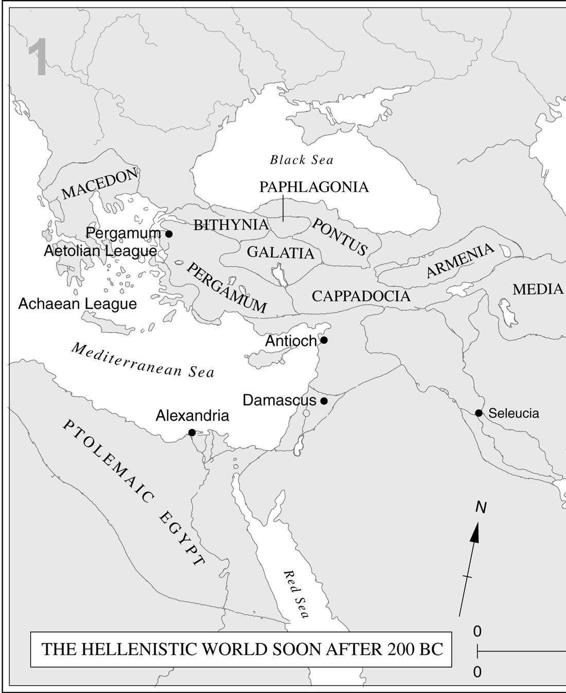

Alexander’s impact was made in the east. He did not reign long enough to affect the interplay of the western Greeks with Carthage, which was the main preoccupation of the later fourth century in the west. In Greece itself things stayed quiet until his death. It was in Asia that he ruled lands no Greeks had ruled before. In Persia he had proclaimed himself heir to the Great King and rulers in the northern satrapies of Bithynia, Cappadocia and Armenia did him homage.

Weak as the cement of the Alexandrine empire must have been, it was subjected to intolerable strain when he died without a competent heir. His generals fell to fighting for what they could get and keep, and the empire was dissolving even before the birth of his posthumous son by Roxana. She had already murdered his second wife, so when she and her son died in the troubles any hope of direct descent vanished. In forty-odd years of

fighting it was settled that there would be no reconstitution of Alexander’s empire. There emerged instead a group of big states, each of them a hereditary monarchy. They were founded by successful soldiers, the

diadochi

, or ‘Successors’.

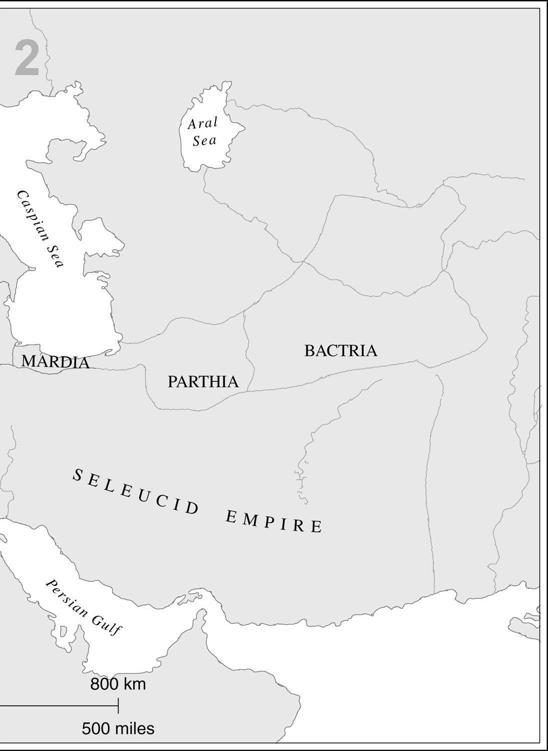

Ptolemy Soter, one of Alexander’s best generals, had at once seized power in Egypt on his master’s death and to it he subsequently conveyed the valuable prize of Alexander’s body. Ptolemy’s descendants were to rule the province for nearly three hundred years until the death of Cleopatra in 30

BC

. Ptolemaic Egypt was the longest-lived and richest of the successor states. Of the Asian empire, the Indian territories and some of Afghanistan passed out of Greek hands altogether, being ceded to an Indian ruler in return for military help. The rest of it was by 300

BC

a huge kingdom of one and a half million square miles and perhaps thirty million subjects, stretching from Afghanistan to Syria, the site of its capital, Antioch. This vast domain was ruled by the descendants of Seleucus, another Macedonian general. Attacks by migrating Celts from northern Europe (who had already invaded Macedonia itself) led to its partial disruption early in the third century

BC

and part of it thenceforth formed the kingdom of Pergamon, ruled by a dynasty called the Attalids, who pushed the Celts further into Asia Minor. The Seleucids kept the rest, though they were to lose Bactria in 225

BC

, where descendants of Alexander’s soldiers set up a remarkable Greek kingdom. Macedon, under another dynasty, the Antigonids, strove to retain a control of the Greek states contested in the Aegean by the Ptolemaic fleet and in Asia Minor by the Seleucids. Once again, about 265

BC

, Athens made a bid for independence but failed.

These events are complicated, but not very important for our purpose. What mattered more was that for about sixty years after 280

BC

the Hellenistic kingdoms lived in a rough balance of power, preoccupied with events in the eastern Mediterranean and Asia and, except for the Greeks and Macedonians, paying little attention to events further west. This provided a peaceful setting for the greatest extension of Greek culture and this is why these states are important. It is their contribution to the diffusion and growth of a civilization that constitute their claim on our attention, not the obscure politics and unrewarding struggles of the

diadochi

.

Greek was now the official language of the whole Near East; even more important, it was the language of the cities, the foci of the new world. Under the Seleucids the union of Hellenistic and oriental civilization to which Alexander may have aspired began to be a reality. They urgently sought Greek immigrants and founded new cities wherever they could as a means of providing some solid framework for their empire and of Hellenizing the local population. The cities were the substance of Seleucid power, for beyond them stretched a heterogeneous hinterland of tribes, Persian satrapies, vassal princes. Seleucid administration was still based fundamentally upon the satrapies; the theory of absolutism was inherited by the Seleucid kings from the Achaemenids just as was their system of taxation. Yet it is not certain what this meant in practice and the east seems to have been less closely governed than Mesopotamia and Asia Minor, where Hellenistic influence was strongest and where the capital lay. The size of the Hellenistic cities here far surpassed those of the older Greek emigrations; Alexandria, Antioch and the new capital city, Seleucia, near Babylon, quickly achieved populations of between one and two hundred thousand.

This reflected economic growth as well as conscious policy. The wars of Alexander and his successors released an enormous booty, much of it in bullion, accumulated by the Persian empire. It stimulated economic life all over the Near East, but also brought the evils of inflation and instability. Nevertheless, the overall trend was towards greater wealth. There were no great innovations, either in manufacture or in the tapping of new natural resources. The Mediterranean economy remained much what it had always been except in scale, but Hellenistic civilization was richer than its predecessors and population growth was one sign of this.

Its wealth sustained governments of some magnificence, raising large revenues and spending them in spectacular and sometimes commendable ways. The ruins of the Hellenistic cities show expenditure on the appurtenances of Greek urban life; theatres and gymnasia abound, games and festivals were held in all of them. This probably did not much affect the native

populations of the countryside who paid the taxes and some of them resented what would now be called ‘westernization’. None the less, it was a solid achievement. Through the cities the east was Hellenized in a way which was to mark it until the coming of Islam. Soon they produced their own Greek literature.

Yet though this was a civilization of Greek cities, in spirit it was unlike that of the past, as some Greeks noted sourly. The Macedonians had never known the life of the city-state and their creations in Asia lacked its vigour; the Seleucids founded scores of cities but maintained the old autocratic and centralized administration of the satrapies above that level. Bureaucracy was highly developed and self-government languished. Ironically, besides having to bear the burden of disaster in the past, the cities of Greece itself, where a flickering tradition of independence lived on, were the one part of the Hellenistic world that actually underwent economic and demographic decline.

Though the political nerve had gone, city culture still served as a great transmission system for Greek ideas. Large endowments provided at Alexandria and Pergamon the two greatest libraries of the ancient world. Ptolemy I also founded the Museum, a kind of institute of advanced study. In Pergamon a king endowed schoolmasterships and it was there that people perfected the use of parchment (

pergamene

) when the Ptolemies cut off supplies of papyrus. In Athens the Academy and the Lyceum survived, and from such sources the tradition of Greek intellectual activity was everywhere refreshed. Much of this activity was academic in the narrow sense that it was in essence commentary on past achievement, but much of it was also of high quality and now seems lacking in weight only because of the gigantic achievements of the fifth and fourth centuries. It was a tradition solid enough to endure right through the Christian era, though much of its content has been irretrievably lost. Eventually, the world of Islam would receive the teaching of Plato and Aristotle through what had been passed on by Hellenistic scholars.