The New Penguin History of the World (50 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

That Roman rule did not satisfy all Roman subjects all the time was even true in Italy itself when, as late as 73

BC

, in the disorderly last age of the Republic, a great slave revolt required three years of military campaigning and was punished with the crucifixion of 6000 slaves along the roads from Rome to the south. In the provinces revolt was endemic, always likely to be provoked by a particular burst of harsh or bad government. Such was the famous rebellion of Boadicea in Britain, or the earlier Pannonian revolt under Augustus. Sometimes such troubles could look back to local traditions of independence, as was the case at Alexandria where they were frequent. In one particular instance, that of the Jews, they touched chords not unlike those of later nationalism. The spectacular Jewish record of disobedience and resistance goes back beyond Roman rule to 170

BC

, when they bitterly resisted the ‘westernizing’ practices of the Hellenistic kingdoms which first adumbrated policies later to be taken up by Rome. The imperial cult made matters worse. Even Jews who did not mind Roman tax-gatherers and thought that Caesar should have rendered unto him what was Caesar’s were bound to draw the line at the blasphemy of sacrifice at his altar. In

AD

66 came a great revolt; there were others under Trajan and Hadrian. Jewish communities were like powder-kegs; their sensitivity makes somewhat more understandable the unwillingness of a Procurator of Judaea in about

AD

30 to press hard for the strict observance of the legal rights of an accused man when Jewish leaders demanded his death.

Taxes kept the empire going. Although not heavy in normal times, when they paid for administration and police quite comfortably, they were a hated burden and one augmented, too, from time to time, by levies in kind, requisitioning and forced recruiting. For a long time, they drew on a prosperous and growing economy. This was not only a matter of such lucky imperial acquisitions as the gold-mines of Dacia. The growth in the circulation of trade and the stimulus provided by the new markets of the great frontier encampments also favoured the appearance of new industry and suppliers. The huge numbers of wine jars found by archaeologists are only an indicator of what must have been a vast commerce – of foodstuffs, textiles, spices, which have left fewer traces. Yet the economic base of empire was always agriculture. This was not rich by modern standards, for its techniques were primitive; no Roman farmer ever saw a windmill and watermills were still rare when the empire ended in the West. For all its idealization, rural life was a harsh and laborious thing. To it too, therefore, the

Pax Romana

was essential: it meant that taxes could be found from the small surplus produced and that lands would not be ravaged.

In the last resort almost everything seems to come back to the army, on which the Roman peace depended, yet it was an instrument which changed over six centuries as much as did the Roman state itself. Roman society and culture were always militaristic, yet the instruments of that militarism changed. From the time of Augustus the army was a regular long-service force, no longer relying even formally upon the obligation of all citizens to serve. The ordinary legionary served for twenty years, four in reserve, and increasingly came from the provinces as time went by. Surprising as it may seem, given the repute of Roman discipline, volunteers seem to have been plentiful enough for letters of recommendation and the use of patrons to be resorted to by would-be recruits. The twenty-eight legions which were the normal establishment after the defeat in Germany were distributed along the frontiers, about 160,000 men in all. They were the core of the army, which contained about as many men again in the cavalry, auxiliaries and other arms. The legions continued to be commanded by senators (except in Egypt) and the central issue of politics at the capital itself was still access to opportunities such as this. For, as had become clearer and clearer as the centuries passed, it was in the camps of the legions that the heart of the empire lay, though the Praetorian Guard at Rome sometimes contested their right to choose an emperor. Yet the soldiers comprised only part of the history of the empire. Quite as much impact was made on it, in the long run, by the handful of men who were the followers and disciples of the man the Procurator of Judaea had handed over to execution.

7

Jewry and the Coming of Christianity

Few readers of this book are likely to have heard of Abgar, far less of his east Syrian kingdom, Osrhoene; yet this little-known and obscure monarch was long believed to be the first Christian king. In fact, the story of his conversion is a legend; it seems to have been under his descendant, Abgar VIII (or IX, so vague is our information), that Osrhoene became Christian at the end of the second century

AD

. The conversion may not even have included the king himself, but this did not trouble hagiographers. They placed Abgar at the head of a long and great tradition; in the end it was to incorporate virtually the whole history of monarchy in Europe. From there it was to spread to influence rulers in other parts of the world.

All these monarchs would behave differently because they saw themselves as Christian, yet, important though it was, this is only a tiny part of the difference Christianity has made to history. Until the coming of industrial society, in fact, it is the only historical phenomenon we have to consider whose implications, creative power and impact are comparable with the great determinants of prehistory in shaping the world we live in. Christianity grew up within the classical world of the Roman empire, fusing itself in the end with its institutions and spreading through its social and mental structures to become our most important legacy from that civilization. Often disguised or muted, its influence runs through all the great creative processes of the last 1500 years; almost incidentally, it defined Europe. That continent, and others, are what they are today because a handful of Jews saw their teacher and leader crucified and believed he rose again from the dead.

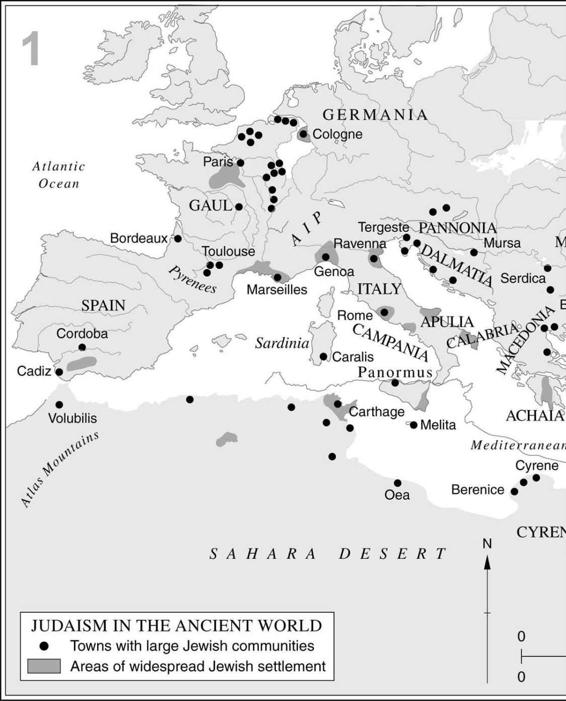

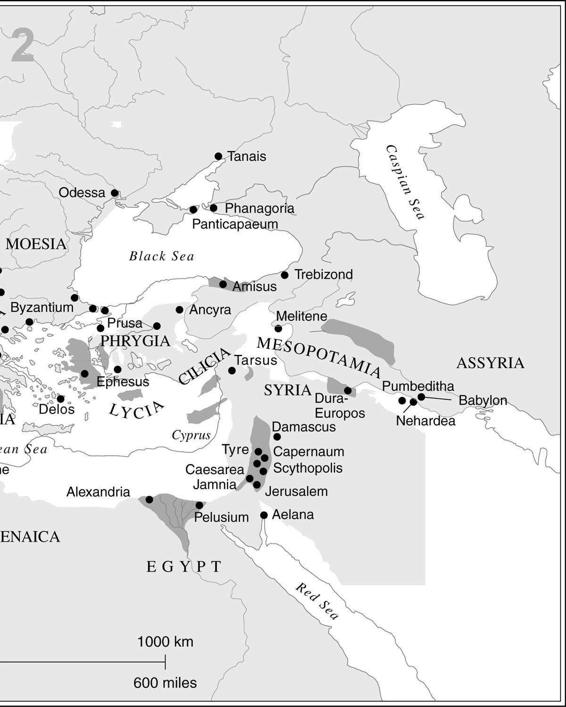

The Jewishness of Christianity is fundamental and was probably its salvation (to speak in worldly terms), for the odds against the historical survival, let alone worldwide success, of a small sect centred upon a holy man in the Roman eastern empire were enormous. Judaism was a matrix and protecting environment for a long time as well as the source of the most fundamental Christian ideas. In return, Jewish ideas and myths were to be generalized through Christianity to become world forces. At the

heart of these was the Jewish view that history was a meaningful story, providentially ordained, a cosmic drama of the unfolding design of the one omnipotent God for His chosen people. Through His covenant with that people could be found guidance for right action, and it lay in adherence to His law. The breaking of that law had always brought punishment, such as had come to the whole people in the deserts of Sinai and by the waters of Babylon. In obedience to it lay the promise of salvation for the community. This great drama was the inspiration of Jewish historical writing, in which the Jews of the Roman empire discerned the pattern which made their lives meaningful.

That mythological pattern was deeply rooted in Jewish historical experience, which, after the great days of Solomon, had been bitter, fostering an enduring distrust of the foreigner and an iron will to survive. Few things are more remarkable in the life of this remarkable people than the simple fact of its continued existence. The Exile which began in 587

BC

when Babylonian conquerors took many of the Jews away after the destruction of the Temple was the last crucial experience in the moulding of their national identity before modern times. It finally crystallized the Jewish vision of history. The exiles heard prophets like Ezekiel promise a renewed covenant; Judah had been punished for its sins by exile and the Temple’s destruction, now God would turn His face again to Judah, who would return again to Jerusalem, delivered out of Babylon as Israel had been delivered out of Ur, out of Egypt. The Temple would be rebuilt. Perhaps only a minority of the Jews of the Exile heeded this, but it was a significant one and it included Judah’s religious and administrative élite, if we are to judge by the quality of those – again, probably a minority – who, when they could do so, returned to Jerusalem, a saving Remnant, according to prophecy.

Before that happened, the experience of the Exile had transformed Jewish life as well as confirming the Jewish vision. Scholars are divided as to whether the more important developments took place among the exiles or among the Jews who were left in Judah to lament what had happened. In one way or another, though, Jewish religious life was deeply stirred. The most important change was the implanting of the reading of the scriptures as the central act of Jewish religion. While the Old Testament was not to assume its final form for another three or four centuries, the first five books, or ‘Pentateuch’, traditionally ascribed to Moses, were substantially complete soon after the return from the Exile. Without the focus of cult practice at the Temple the Jews seem to have turned to weekly meetings to hear these sacred texts read and expounded. They contained the promise of a future and guidance to its achievement through maintenance of the

Law, now given a new detail and coherence. This was one of the slow effects of the work of the interpreters and scribes who had to reconcile and explain the sacred books. In the end there was to grow out of these weekly meetings both the institution of the synagogue and a new liberation of religion from locality and ritual, however much and long Jews continued to pine for the restoration of the Temple. The Jewish religion could eventually be practised wherever Jews could come together to read the scriptures; they were to be the first of the peoples of a Book, and Christians and Moslems were to follow them. It made possible greater abstraction and universalizing of the vision of God.

There was a narrowing, too. Although Jewish religion might be separated from the Temple cult, some prophets had seen the redemption and purification which must lie ahead as only to be approached through an even more rigid enforcement of what was now believed to be Mosaic law. Ezra brought back its precepts from Babylon and observances which had been in origin those of nomads were now imposed rigorously on an increasingly urbanized people. The self-segregation of Jews became much more important and obvious in towns; it was seen as a part of the purification which was needed that every Jew married to a gentile wife (and there must have been many) should divorce her.

This was after the Persian overthrow of Babylon. In 539

BC

some of the Jews took the opportunity offered to them and came back to Jerusalem. The Temple was rebuilt during the next twenty-five years and Judah became under Persian overlordship a sort of theocratic satrapy. In the fifth century, when Egypt revolted against Persian rule, this was a strategically sensitive area, and it was governed lightly and with the help of the native priestly aristocracy. This provided the political articulation of Jewish nationhood until Roman times.

With the ending of Persian rule, the age of Alexander’s heirs brought new problems. After being ruled by the Ptolemies, the Jews eventually passed to the Seleucids. The social behaviour and thinking of the upper classes underwent the influence of Hellenization; this sharpened divisions by exaggerating contrasts of wealth and differences between townsmen and countrymen. It also separated the priestly families from the people, who remained firmly in the tradition of the Law and the Prophets, as expounded in the synagogues. The great Maccabaean revolt broke out (168–164

BC

) against a Seleucid king of Hellenistic Syria, Antiochus IV, and cultural ‘westernization’ approved by the priests but resented by the masses. Antiochus had tried to go too fast; not content with the steady erosion of Jewish insularity by Hellenistic civilization and the friction of example, he had interfered with Jewish rites and profaned the Temple by

seeking to turn it into the temple of Olympian Zeus. Perhaps, though, he only wished to open the temple complex to all worshippers, as was normal for any temple in a Hellenistic city. After the revolt had been repressed with difficulty (and guerrilla war went on long after), a more conciliatory policy was resumed by the Seleucid kings. It did not satisfy many Jews, who in 142

BC

were able to take advantage of a favourable set of circumstances to win an independence which was to last for nearly eighty years. Then, in 63

BC

, Pompey imposed Roman rule and there disappeared the last independent Jewish state in the Near East for nearly two thousand years.