The Pentagon: A History (19 page)

Read The Pentagon: A History Online

Authors: Steve Vogel

In the first weeks of construction, the lagoon was attacked from both land and water. Dredges scooped out silt and deepened the channel. Working behind the safety of a clay dike, steam shovels excavated the ground next to the channel. Workers drove well points—hollow pointed rods—into the ground and pumped out water, lowering the water table and further protecting against flooding. The excavators dug fourteen feet below the normal high-tide level of the Potomac. Then a dipper dredge—a floating dredging machine with a machine-operated bucket working on an arm—opened a passage through the dike. The batching plant, constructed simultaneously, was soon ready for deliveries.

More than one million cubic yards of ground was excavated to enlarge the lagoon, and the muck was dumped immediately to the northwest, raising the level of that ground. In effect, more than a hundred acres of marginal land was being converted into seventy acres of usable land. Ironically, tons of dirt that Potts & Callahan trucks had hauled to Washington-Hoover Airport five years earlier to fill low areas had to be dug out to expand the lagoon. “We have accomplished a total of nothing,” a worker groused.

We’d better leave town

A month after groundbreaking, a fundamental decision had yet to be made: What material would be used to construct the building’s walls?

The original plan was to make the building’s exterior brick. Somervell had told a House subcommittee in July that limestone was not being considered. “We did not even dream of getting anything that good,” he had said. Yet the tentative plans now called for 150,000 cubic yards of Indiana limestone on the building’s exterior.

The light-colored, fine-grained stone was known for its durability and ease of shaping. It had been used in city halls, churches, and statehouses across the land, as well as the National Cathedral in Washington and the Empire State Building in Manhattan. McShain had pushed for limestone on the building’s exterior. “I am sure that we all want to be quite proud of this building after it is finished,” McShain wrote Groves. “Therefore it is essential that the exterior of the building be very presentable in order to avoid public criticism.”

McShain had an ally in the limestone industry, which had fallen on hard times, and, aided by Senator Raymond Willis of Indiana, was lobbying hard for limestone on the new War Department building. “Bricklayers are all extremely busy whereas stone setters are literally walking the streets in every large city,” the director of the Indiana Limestone Institute wrote Somervell. The “limestone boys,” a War Department official later said, succeeded in making the switch from bricks. Groves thought limestone was a mistake and argued against it repeatedly with Somervell. A brick exterior “would indicate that we were not extravagant,” Groves later wrote. But Somervell was persuaded that limestone would lend a dignity to the building at a reasonable cost—$295,000—and if it made the limestone boys and the senator from Indiana happy, all the better. The Commission of Fine Arts approved limestone, but a decision was still needed from Roosevelt, who had reserved final judgment on the exterior.

The limestone debate was only a warm-up to a far more serious disagreement over the rest of the walls. Each of the building’s five concentric rings was to have exterior walls on both sides. In essence, ten pentagonal-shaped walls would be constructed around the entire length of the building. The outermost wall would have limestone facing, if Roosevelt approved. The question was what to put on the other nine walls, as well as the walls of the inner-court stairways, bridge passageways, and various approaches to the building. An enormous amount of wall space was at stake—more than 1.1 million square feet.

McShain and Groves thought it easiest and most economical to simply use brick. But Bergstrom, borrowing from designs he had used often in Southern California, wanted to use architectural concrete, a technique that made ornamental use of concrete. Rough-sawn boards would be used as forms, giving the concrete a texture reflecting the pattern of the grain in the boards. A gap would be left between the eight-inch boards, so the concrete would ooze out and form a ridge. The forms had to be stripped with great care to avoid breaking the ridges. Skilled concrete finishers would brush wet grout on the walls to give them the proper color and texture. It would be painstaking work, “a most expensive procedure,” as Groves said. The effect was meant to simulate limestone; ironically, it would have been cheaper just to use limestone, Luther Leisenring, the chief of the architects’ specifications section, later told Army historians.

McShain was beside himself, predicting disaster. Architectural concrete had been used sparingly on the East Coast, and McShain’s crews were unfamiliar with the technique. It would prolong construction by six months or more, he warned, and increase the cost of the walls by $650,000. Groves conceded that architectural concrete would look better than brick but called it “a terrible thing from the cost standpoint and a time standpoint.”

Late on the morning of October 10, Somervell slipped into the Oval Office with Bergstrom to decide the controversy with Roosevelt. The general recommended facing the exterior of the building with Indiana limestone. Roosevelt raised no objection, insisting only that the building have no marble, for the sake of appearing thrifty.

Next Bergstrom made the case for using architectural concrete for the other exterior walls, showing the president photographs of a building in Los Angeles he had designed using the technique. Roosevelt was pleased with the look and approved architectural concrete, despite the added cost.

“The president thinks it is swell,” Groves glumly told McShain that afternoon.

The fight was not over. Groves ordered three sample walls built, each about twenty feet long by twelve feet high, complete with windowsills. One was to be of an attractive colored faced brick, one of architectural concrete, and one of Indiana limestone, to see how they compared.

Inspecting the concrete wall after it set, McShain was horrified. The concrete was badly honeycombed with voids caused by air. At 8:45

A.M.

on October 14, McShain called Groves in a lather. “I went over the sample with Bergstrom and between you and me, Colonel, if they’re going to let that go I think we’d better leave town,” McShain said.

An appeal had to be made to Somervell and Roosevelt, McShain argued. “I still want the general to see it and if possible we should try to prevail on the President, because what we do here—I don’t care whether you and I oppose it—it’s going to reflect on us sooner or later,” McShain said.

“Of course it’s bound to,” Groves agreed.

“We are the ones responsible for the job because Bergstrom will be forgotten,” McShain said.

Groves pressed Somervell to bring the matter to Roosevelt. “Of course the President decided the way Somervell wanted,” Groves later said.

The president was “emphatic in his disapproval of the use of brick, either red or cream colored,” Somervell reported. The walls would be made of architectural concrete.

“Well, it’s settled,” Groves told Somervell. “I won’t say anything more but I bet you didn’t treat me fair.”

McShain, who prided himself on his ability to predict costs, said his estimates for the walls were worthless now. “I was only judging what a good architect would do in designing it,” he told Groves. “I didn’t anticipate the intentions of a Californian.”

It’s going to be a whopper

Newspaper and magazine reporters were hounding George Holmes, Somervell’s public relations man, for some news—any news—about the new building. Somervell decided progress was far enough along that he could afford to go public with a press release October 7. Reporters were confounded by what they learned.

Each face of the five-side exterior would stretch 921 feet. The pentagonal rings would surround a six-acre landscaped interior court. A large bus terminal would be built in the basement, with two lanes and fourteen loading stations. Two parking lots would accommodate eight thousand automobiles. The whole building would be air-conditioned, and its main concourse lined with a cafeteria, drugstore, barbershop, and other shops and facilities. The 320-acre site, which included separate heating and sewage plants, would be landscaped and beautified. Stepped terraces and plazas would lead up from the lagoon. Access roads would crisscross the property and new highways built to bring employees to work.

It sure did not sound as if the size of the building had been cut in half. Yet the release conspicuously noted that “the size, design and location of the building have received the personal attention of the President and the plans as announced reflect the instructions issued to Brigadier General Brehon B. Somervell, Chief of Construction.”

Reporters were further alarmed by the high amount listed in the release for the construction contract, $31.1 million—a figure that did not even include the architectural and engineering costs that raised the total to $33.2 million. “The War Department’s new office building in Arlington, Va., will be a dream building after all, costing some 31 million dollars,” the

Post

reported suspiciously.

The release described the building as “a three-story building, with basement,” but that was a deliberate deception, directed by Somervell. The “so-called basement was above ground,” so the building was really four stories. Somervell ordered the basement nomenclature to disguise the inconvenient fact that he had promised a three-story building in his congressional testimony. No mention was made about the sub-basement that was planned, or for that matter, the sub-sub-basement.

Indeed, no information at all had been included in the press release about the total amount of space in the building. Reporters scrambled to find details of the dimensions from closed-mouthed War Department officials but met with little success for several days. An Army press spokesman, employing no little sophistry, told the

Star

that it was impossible as of yet to figure out the size of the building because the plans were not finished.

Finally, leaving the White House around noon on October 10 after a meeting with the president, Somervell was cornered by reporters who demanded answers. “No one is interested in the size of the building except real estate operators and war profiteers,” the general insisted. Pressed, Somervell acknowledged the total size of the building would be more than four million square feet, or over four-fifths the size of the original proposal.

Conferring with local architects, the

Star

pieced together the truth. The plans for Somervell’s building allotted 125 square feet per employee, a generous amount of space by the standards of the day given the emergency conditions. Some War Department employees were getting by then in as little as forty-five square feet. By halving the space allotment per worker, the building could—with the stroke of a pen—hold forty thousand workers. The building was being constructed with enormous office bays rather than individual suites, so it would be a simple matter of moving in more desks.

The working papers of Witmer, Bergstrom’s top assistant, confirm the theory, showing the architects were working with two sets of estimates, one showing capacity of 19,530 workers at 125 square feet per person, the other 37,500 workers at 65 square feet per person.

Speaking to reporters at the White House, Somervell called it “utterly ridiculous” to suggest he had circumvented Roosevelt’s directions. “Do you think any government official in his right mind would fail to conform to the President’s orders?” he asked. Indeed, despite the press suspicion, Somervell told Roosevelt on August 29 that the building would be four million square feet, and the president raised no objection. Roosevelt, seeking to dampen the public controversy, probably was an accomplice in hiding the true size of the building; Somervell likely spoke the truth a month earlier when he told Surles, the public relations chief, that the president did not want the information released.

As for reporters’ doubts that such an elaborate building would ever be used to store records, Somervell insisted it would make a “dandy” archives. Asked if the War Department would ever be willing to give up the building, the general coyly said, “Let’s get through the emergency first.”

Skeptical reporters consulted with Frederic Delano, who confirmed that Somervell’s building adhered to the compromise agreement that he had signed and the president had approved. The commission was “by no means satisfied,” Delano told reporters. But, he added, “we treated it as a war emergency and so accepted it.”

The newspapers broke the news about the building to the public. The

Times-Herald

sounded bitter about having been duped: “It was finally decided once and for all, positively and definitely yesterday, that the size of the new War Department Building hasn’t been cut in half and that it is going to be a whopper.”

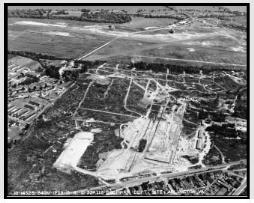

An aerial view of the site on September 15, 1941, with the Goodyear blimp

Enterprise

visible in the background moored to the ground.