The Perfect Heresy (23 page)

Read The Perfect Heresy Online

Authors: Stephen O'Shea

Simon de Montfort was hearing dawn mass when the attack came. Messengers arrived three times during the service, imploring the count to ride to the rescue of the cat’s embattled defenders. The men of Toulouse were clambering down ladders, rushing across the moats, slashing their way ever closer to the tower. The last of the messengers cried out to his lord, exasperated, “This piety is disastrous!” Unflappable, Simon waited for the consecration, the moment of the mass when the host is elevated, then crossed himself, snapped on his helmet, and said, “Jesus Christ the righteous, now give me death on the field or victory!”

Simon and his knights mounted their destriers and galloped

directly into the melee at the foot of the cat, swords and axes swinging. Within minutes, the tide had turned, and the warriors of Toulouse were staggering backward, badly bloodied, scrambling for the safety of the town. On the walls, the dismayed defenders loaded catapults and drew bowstrings to cover the retreat. An arrow tore through the head of the horse of Guy de Montfort, Simon’s brother and comrade-in-arms since their campaign in Palestine. The animal reared up, dying, then a bolt from a crossbow caught Guy in the groin. Their screams of pain carried over the tumult. Simon saw his brother down. He scrambled to dismount when, as the chronicle relates, a mangonel atop the parapet let fly:

This was worked by noblewomen, by little girls and men’s wives, and now a stone arrived just where it was needed and struck Count Simon on his steel helmet, shattering his eyes, brains, back teeth, forehead and jaw. Bleeding and black, the count dropped dead on the ground.

Two crusaders rushed over and draped a blue cape over the body.

Word of Simon’s death spread in all directions. Men stepped back, thunderstruck, lowering swords and shields. There was a stunned silence, which was soon broken by a great cheer, swelling louder and louder as the news swept through Toulouse.

Lo lop es mòrt!

(The wolf is dead!) Bells, drums, chimes, tabors, clarions sounded—the noise lasted all day and night.

Simon’s eldest son, Amaury, gathered up the corpse and carted it out of sight of the revelers.

For Toulouse, the memory of Muret had been avenged and the devil defeated. For the crusaders, the disaster was total. Within a month the siege was lifted. The giant cat had been

burned by the defenders and one last desperate assault, on July 1, firmly repulsed. The man who had trounced Languedoc, befriended Dominic, burned the Cathars, bullied the greatest medieval pope, was dead at fifty-three.

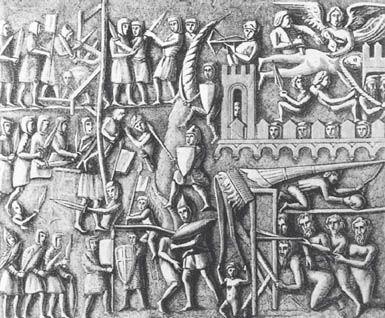

Drawing from thirteenth-century bas-relief in St. Nazaire church, Carcassonne, showing a scene from the siege of Toulouse and believed to depict the death of Simon de Montfort

(Mansell Collection/Time, Inc.)

As was the custom, his body was boiled until the flesh and organs fell off the bone, and his remains were placed in an oxhide pouch. This was interred at St. Nazaire Cathedral in Carcassonne, amid the requisite ecclesiastical pomp. It was his enemy, the anonymous chronicler of the Cathar wars, who penned a devastating obituary that, even today, some Toulousains can recite from memory:

13.The epitaph says, for those who can read it, that he is a saint and martyr who shall breathe again and shall in wondrous joy inherit and flourish, shall wear a crown and be seated in the kingdom. And I have heard it said that this must be so—if by killing men and shedding blood, by damning souls and causing deaths, by trusting evil counsels, by setting fires, … seizing lands and encouraging pride, by kindling evil and quenching good, by killing women and slaughtering children, a man can in this world win Jesus Christ, certainly Count Simon wears a crown and shines in heaven above.

The Return to Tolerance

W

AR DID NOT CEASE IN LANGUEDOC

, but victory changed camps. The Occitan nobles, inspired by the successful defense of Toulouse, at last united to press their advantage against the French. A large punitive expedition organized in 1219 could not check the rebellion. Preached by the new pope—Honorius III—and led by Philip Augustus’s son Louis, the crown prince of France, the crusade fell victim to its participants’ punctilious observance of the quarantine. Louis and his men returned to Paris after forty days of campaigning, their only accomplishment of note a cold-blooded massacre that mystified even their supporters. Every man, woman, and child in Marmande, an inoffensive market center of about 7,000 inhabitants in western Languedoc, was methodically put to the sword. Having thus doffed his cap to the precedent of Béziers, the future king then spent a few dilatory weeks outside the walls of Toulouse before torching his siege engines and riding home. Amaury

de Montfort, Simon’s son, was left on his own to quell the rebellion as best he could.

Thirteenth-century troubadour

(Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris)

But Amaury was not the man his father had been. He did not inherit Simon’s steely decisiveness or any of his father’s talent for tactical atrocity. In the six years of battle, siege, and skirmish following Simon’s death, Amaury was consistently bested by Raymond the younger and Roger Bernard of Foix. The huge Lateran land grant to the Montforts steadily shrank with every castle lost and garrison evicted. The major towns refused to open their gates to the French—and to their allies in the upper ranks of the clergy. The displaced leaders of the Church in Languedoc, including Fulk of Toulouse, had to go into exile in Montpellier.

The worst insult to the Catholic bishops came not from the battlefield, nor even from places that reverted to conspicuous Catharism, like the castles of Cabaret or the workshops of Fanjeaux. The bad news for the hierarchy came from Catholic believers. Many of them now viewed the leaders of the Church as a noxious, national enemy, to be denied the estates and benefices from which they had drawn their income. In the Occitan mind,

Innocent’s reasoning about heretics had been stood on its head: It was the higher clergy, rather than the heretics, who should be charged with treason. The bishops were seen as accomplices of the hated French. The troubadours, already ill disposed toward killjoy prelates and papal legates, composed scathing

sirventes

about the warlords with the crosiers. The troubadour Guilhem Figueira began one song:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A discouraged Fulk, who had not been allowed to return to his city since he had taken part in the siege of Lavaur in 1211, tried

unsuccessfully to have the pope relieve him of his post as bishop of Toulouse.

If such bad feelings had sparked a massive defection from the Church, the bishops could have thrown up their hands and, as is still the custom in some quarters, blamed the Antichrist. But there was no great defection. As if to compound the insult to episcopal dignity, Catholic piety in Languedoc remained strong. Throughout the 1220s, bequests to monasteries continued to be made by burgher and knight, secular priests celebrated mass for devout congregations, and the fledgling Dominican order found ready audiences for its preaching. Even during the darkest hours of crusader sieges, the local clergy within the towns of Languedoc had suffered no manhandling from the laity. Moreover, many in the lower orders of the Church had taken up the Occitan cause. On the death of Simon de Montfort, for example, it was the priests of Toulouse who rang the bells and lit the votive candles. Resentment was directed squarely at the bishops who had brought ruin to a formerly rich land. It was they, not the Perfect, who were shunned by the people.