The Perfect Heresy (26 page)

Read The Perfect Heresy Online

Authors: Stephen O'Shea

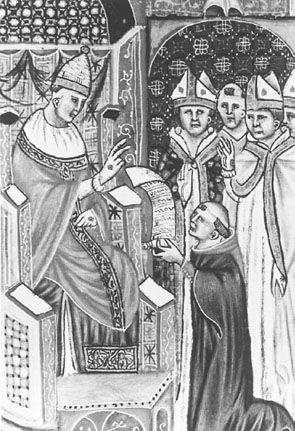

Yet the ceremony was not an exact duplicate of the scourging at St. Gilles. This time the onlookers whispered to each other in French, not Occitan, for the solemnities took place in the heart of Paris, on the Ile de la Cité. On this Thursday before Easter, Raymond and Romano performed their dark duet before the facade of the city’s new cathedral, Notre Dame. Rising high over the warren of half-timbered dwellings reflected in the gray waters of the Seine, the elegant stone structure, its statuary and vaulting painted every color of the rainbow, stood as a spectacular symbol of cultural exuberance. Unlike the land of the Cathars, France was entering its springtime.

The scourging of Raymond VII of Toulouse in Paris

(Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris)

The two men went into the crowded church, past the nobility of the north, and walked down the nave to the high altar. “It was a great shame,” wrote a chronicler, “to see so noble a prince, who had long held his own against powers both mighty and many, thus haled to the altar bare-footed, clad only in shirt and breeches.” Raymond had agreed to undergo this degrading day for the sake of a lasting peace. His once huge domains were reduced to a truncated, landlocked principality encompassing Toulouse and a few minor cities to the north and west. The French Crown took what had belonged to the Trencavel family,

as well as all of Raymond’s possessions on the west bank of the Rhône.

A triumphant Te Deum resounded in the stone vault of the cathedral as the canons of Notre Dame were directed to give voice to their joy. It had been almost twenty years since one of their number, William of Paris, weighted trebuchets and adjusted mangonels for the greater glory of God and his servant Simon de Montfort.

From her place of honor, Blanche of Castile surveyed the instructive tableau of count and cardinal standing before her. She had done not man’s work but Christ’s. Beside her on this memorable Holy Thursday stood her eldest son, Louis. Once grown to manhood, the boy, as King Louis IX, would become the most devout monarch of Europe, eventually earning sainthood for his death on crusade near Tunis. A persecutor of heathen and heretic, Muslim and Jew, St. Louis inherited his mother’s extravagant Iberian faith. Across the island from Notre Dame, he would erect the Gothic masterpiece of the Sainte Chapelle, an exquisite stone reliquary for the treasures he had bought from wily traders: a vial of the Virgin’s milk, the crown of thorns, and dozens of other costly frauds peddled to the credulous crusader king. In watching the spectacle of Raymond VII’s humiliation, the twelve-year-old future saint may have acquired his taste for devotional brio.

To receive the blessing of the cardinal, Raymond sank to his knees. The pose was apt, for the count had acceded to crippling demands in order to wring peace from the Church and the Crown. Not only were his lands cut in half, but his treasury was to be badly bled for the rest of his life. His sole child, a daughter aged nine, was forced into a marriage with one of Louis’s many siblings; when they died childless forty-two years later, the

county of Toulouse automatically became a part of France. Romano and Blanche also made sure that Raymond subsidized the hunt for heresy. A university was to be established later in the year in Toulouse, its four doctors of theology paid by the count to train future generations of Occitan clerics in the intricacies of orthodox belief. A posse of scholars would henceforth seek out and destroy the remnants of Catharism.

When Raymond, tall and handsome at thirty-one, emerged from the portals of Notre Dame, he was once again a legitimate Christian lord in good standing with both Paris and Rome. His enemies thought him lucky to have been granted even a pittance. Thanks to the usual tangle of noble bloodlines, Raymond of Toulouse and Blanche of Castile had a grandmother in common, the great twelfth-century queen of both France and England, Eleanor of Aquitaine. Were it not for that sentimental connection, Blanche might not have yielded an acre of land to the count.

The bonds of cousinhood stretched only so far. Immediately after the crowds had dispersed on the Ile de la Cité, Raymond and his entourage were carted across the river to the Right Bank and led into the brooding stone fortress of the medieval Louvre. They were held hostage there for six weeks, while the armies of the north tore down the fortifications of Toulouse, reduced dozens of castles to rubble, installed a royal seneschal in Carcassonne, and brought about all the other changes spelled out in the draconian treaty. The ceremony at Notre Dame may have had a touch of déjà vu, but in Languedoc nothing would be as it was before.

Inquisition

O

N

A

UGUST

5, 1234, a wealthy old lady of Toulouse said on her deathbed that she wanted to make a good end.

Her servants scuttled down the stairs and out into the street. They had to find a Perfect, hidden somewhere in the attics and cellars of the city. If they were lucky, perhaps the revered Guilhabert of Castres, the Cathar bishop of Toulouse, had come down from the safety of Montségur on a discreet visit to a believer in town. The servants made cautious inquiries at the houses of those who quietly shared the old lady’s faith. In time, they returned with what they were seeking—a Perfect, who administered the consolamentum to the ailing woman, then left as stealthily as he had come.

One member of the household had not returned. He had dashed across town to the Dominican monastery, then ducked into its chapel. He made his way round the darkened ambulatory and knocked on the sacristy door.

William Pelhisson, a Dominican inquisitor whose memoir of Languedoc immediately after the end of the Albigensian Crusade gives a vivid glimpse of the altered circumstances of life in Toulouse, was most probably in the sacristy that day. With Pelhisson and his fellow friars was Raymond du Fauga, the bishop of Toulouse, also a Dominican. The bishop was changing out of the vestments in which he had just said mass in honor of the newly canonized Dominic. August 5, 1234, marked the very first time that St. Dominic had his feast day celebrated.

Raymond, William, and the other friars in the sacristy listened to their visitor’s tale: A Cathar believer, in the delirium of death throes, lay helpless in her bed just a few doors down from the cathedral. The bishop sent a servant out to fetch the prior of the Dominicans back from his midday meal. Bishop Raymond was always given to the grand gesture; his inaugural act on taking over from the deceased Fulk in 1232 had been to bully Raymond VII of Toulouse into hunting down and executing nineteen Perfects on the Montagne Noire. There was a chance to put on a similarly instructive show for the populace of Toulouse.

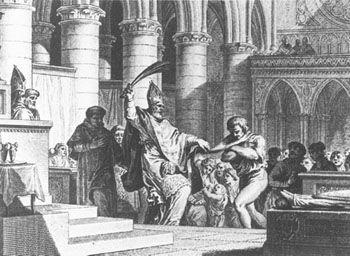

According to Pelhisson, the traitorous servant led the bishop, the prior, and the other Dominicans into the woman’s house. They climbed the narrow stairs and entered her room. Her relatives shrank back into the shadows on seeing the friars arrive. The dying woman’s in-laws, the Borsier family, had long ago fallen under suspicion of heresy. One of them whispered a warning to the sickbed, telling the dying woman that the “Lord Bishop” had arrived.

She apparently misunderstood, for she addressed Raymond du Fauga, the Catholic bishop, as if he were Guilhabert of Castres, the Cathar Perfect.

Bishop Raymond did not correct her mistake. Instead, he

pretended to be the Cathar holy man, so that the woman would damn herself all the more thoroughy. As the others in the room watched, Raymond questioned her at length, eliciting from her a full profession of her heretical faith. He stood over the bed and, according to Pelhisson, exhorted the woman to remain true to her beliefs. “The fear of death should not make you confess anything other than that which you hold firmly and with your whole heart,” the bishop advised with mock concern for her soul. When the woman agreed, he revealed his true identity and pronounced her an unrepentant heretic subject to immediate execution.

Since she was too feeble to move on her own, the woman was lashed to her bed. It was carried downstairs and into the street. Raymond led the curious procession past his cathedral and into a field beyond the city gates. A bonfire had been lit in expectation of their arrival. News of the spectacle spread throughout Toulouse. A large crowd assembled, then watched, openmouthed, as a barely conscious woman, with just hours left in her natural life, was thrown into the flames.

“This done,” the Dominican eyewitness noted, “the bishop, together with the monks and their attendants, returned to the refectory and, after giving thanks to God and St. Dominic, fell cheerfully upon the food set before them.”

The papacy of Gregory IX, begun in 1227, marked a fevered new departure in the race to silence dissent. The notion of a permanent papal, as opposed to an episcopal, heresy tribunal began to gain ground. Prior to Gregory’s ascension to power in Rome, the task of ferreting out freethinkers had been left to

the bishops. For the preceding fifty years, successive popes had repeatedly exhorted their spiritual viceroys to arrest and try heretics in specially constituted courts. After conviction, the condemned would then be, as clerical euphemism had it, “relaxed to the secular arm”—that is, they were turned over to the local nobility for speedy incineration. The only problem with these diocesan courts was that they were exceptional. Most bishops lacked the intellectual stamina, and perhaps the stomach, to launch a sustained slaughter of the strayed sheep of their flock. Despite the great doctrinal housekeeping at the Lateran in 1215, many bishops and priests were still unsure of what exactly constituted heresy; others were compromised or complaisant because

of their ties of kinship to the leading families of their diocese; and others were simply corrupt. Innocent had spelled out his frustrations in his opening sermon at the Fourth Lateran Council: “It often happens that bishops, by reason of their manifold preoccupations, fleshly pleasures and bellicose leanings, and from other causes, not least the poverty of their spiritual training and lack of pastoral zeal, are unfitted to proclaim the word of God and govern the people.” There could be no effective policing of souls as long as the bishops were left in charge.