The Perfect Heresy (33 page)

Read The Perfect Heresy Online

Authors: Stephen O'Shea

The exiles wandered through Aragon and Catalonia, settling only temporarily wherever they went, always ready to move

on when better opportunités beckoned or when the Aragonese Inquisition came too close. To allay suspicion, Bélibaste posed as a married man. Raymonda Piquier, a Languedoc native who had lost track of her husband in the confusion of arrests at home, shared the Perfect’s house and, when traveling, his room. The two became lovers. Despite this breach of the vows taken at the consolamentum, Bélibaste kept up appearances of celibacy for nearly a decade, and his indulgent followers feigned ignorance of the real relationship between their Perfect and his housekeeper. In 1319, the shepherd Peter Maury, an inveterate bachelor from Montaillou, was hectored by Bélibaste into wedding Raymonda. The Perfect performed a hasty marriage ceremony—yet another innovation for a faith that had no such sacrament—and Peter and Raymonda moved in together. Within a week, Bélibaste had released them from their vows and brought Raymonda back under his roof. Several months later, she gave birth to a child; Peter Maury, obligingly, acknowledged paternity.

For all his failings, the last of the Cathar Perfect worked hard to edify his flock. The interrogation transcripts of his credentes—most were eventually ensnared by the Inquisition—show that Bélibaste’s sermons were remembered for years after his disappearance. The Cathar preached movingly and commanded respect. He spoke at length of never giving in to the sin of despair, of the need to love one another, of how the good God awaited us all beyond the evil veil of creation. He never wavered in his belief that the world was ruled by maleficent powers and that four demons—the king of France, the pope, the inquisitor at Carcassonne, the bishop of Pamiers—were especially active in keeping people from finding their true salvation.

Knowing himself to be compromised, he refused to administer the consolamentum; it would, he assured his anxious listeners, be given to them freely in the afterlife by a Perfect-turned-angel.

The community at last found permanent homes in Morella and Sant Mateu, towns near the delta of the River Ebro, south of Tarragona. It was a long journey—more than 200 miles—from Languedoc, yet not far enough away for the seemingly serendipitous to occur. One day in 1317, a certain Arnold Sicre, an inhabitant of Ax-les-Thermes, stumbled across the small settlement of his exiled compatriots. The coincidence was hailed as providential. Arnold claimed to have the “understanding of the Good”; his mother, Sibyl Bayle, had been a prominent believer who was burned by the Inquisition, as was his brother, Pons Bayle, one of Peter Autier’s inner circle of Perfect. The more suspicious of the villagers pointed out that Arnold’s father, a notary, had soured on Catharism and helped organize the raid on Montaillou. Even the easygoing Bélibaste had his doubts. Although Arnold boasted of having known the Autier brothers, the newcomer was woefully ignorant of the basic practices of Catharism. He couldn’t perform the melioramentum, the ritual greeting extended to the Perfect, and he had the gaucheness to bring red meat to Bélibaste’s table.

Arnold Sicre assured the skeptics that he had found what he was seeking. He apprenticed as a shoemaker in Sant Mateu and within weeks was accepted as a member of the secretive Cathar community. He was assiduous in attending the sermons of Bélibaste and soon caught up with the others in his knowledge of dualist mythology and doctrine. He became one of the Perfect’s preferred companions; he may even have been considered as a possible successor to Bélibaste, with or without the consolamentum. As the months turned into years, Arnold seemed content

with his modest life, his only regret the beloved Cathar relatives he had left on their own in the mountains of Languedoc near Andorra. His rich aunt and beautiful maiden sister were all by themselves, bereft of the spiritual solace he received in Catalonia. Bélibaste at last instructed Arnold to go to Languedoc and fetch them. A nubile Cathar bride was needed for one of the bachelor faithful, and a wealthy benefactress was always welcome.

After several months’ absence, Arnold returned, alone, with the news that his aunt, Alazaïs, was now gout-ridden and too frail to travel, and his sister, a loyal niece, had chosen to stay with the old lady. Both women, however, were overjoyed at the news he brought of fellow believers. The aunt, Arnold reported, had bestowed a hefty dowry on his sister and said she was willing to give far more to the struggling exiles. Thanks to her liberality, a free-spending Arnold was able to make the Christmas of 1320 the most pleasant in memory for the outcasts. His failing aunt had opened her purse and made but one request: to be blessed by a good Christian before her death. And his sister, Arnold added, was pining to meet her suitor. Surely, they deserved to be visited.

The longtime companions of the Perfect counseled caution. Bélibaste had barely escaped Languedoc a dozen years ago, and his presence was essential in Morella and Sant Mateu to keep the last ember of Catharism aglow. It would be folly to return to the land of persecution. Arnold quieted their misgivings by pointing out that a safe, short trip to his aunt’s estate would benefit the entire community.

In the spring of 1321, William Bélibaste, Arnold Sicre, Arnold Marty, the prospective husband for Sicre’s sister, and the ever-faithful shepherd Peter Maury headed north toward home. A soothsayer had warned Bélibaste that he would never return

to Catalonia, but the Perfect ignored this advice, as well as the appearance of two magpies—a bad omen if seen in a pair—that swooped across his path while he trudged through the back-country of Barcelona. A mixture of conscientiousness and cupidity impelled Bélibaste forward on his mission to give solace and receive reward at the house of the elderly Alazaïs. Yet as the peaks of the Pyrenees grew taller on the horizon and the dangers of Languedoc neared, the old doubts about Arnold Sicre returned.

Prior to crossing the Ebro on their journey north, as Arnold Sicre subsequently told the Inquisition, Belibaste and Maury decided to get him drunk as part of the age-old ruse of

in vino ventas

. At the riverside inn where they put their plan into effect, the younger man saw through the scheme and surreptitiously dumped out the goblet that his dinner companions took pains to fill and refill. Faking fall-down intoxication, Arnold eventually let Peter Maury help him off to bed. Once they were in his room, Arnold dropped his trousers and got ready to urinate on the pillow. Maury dragged him outside and as the younger man tottered in the darkness, suggested that they betray Bélibaste and collect the handsome price on his head. To which Arnold protested, “I cannot believe that you would do such a thing! I would never let you get away with it!” He staggered back to his bed and was soon emitting a stream of counterfeit snores. Maury returned to Bélibaste and told him that they should stop worrying.

Within a week, the small party from Sant Mateu had reached an outlying possession of the counts of Foix, a small, exiguous mountain valley on the southern slopes of the Pyrenees near Andorra. They slept their first night in Castellbò; the second, in the village of Tirvia. The next dawn, an armed posse broke down their door and placed them under arrest. Arnold Sicre had tipped off the Inquisition. He was, as Bélibaste moaned in horror from his dungeon, “a Judas.”

Bishop and Inquisitor Jacques Fournier, who became Pope Benedict XII

(Roger-Viollet, Paris)

In fact, he was far worse. Throughout his lengthy stay in Catalonia, Arnold had been working for Bishop Fournier, the inquisitor of Pamiers. The coincidence of his arrival, his devotion to dualism, his generous aunt and willing sister—all had been the invention of a genius of deceit. The money Arnold spent the previous Christmas had come from the treasury of Fournier, an advance on the large reward he would earn by

bringing in Bélibaste. But that was not all; the bounty hunter had also struck a bargain with the bishop whereby he would recover the property confiscated from his heretical mother, Sibyl Bayle. Arnold became a rich man. After more than a century of double-dealing—the violated safe-conduct offered to Raymond Roger Trencavel, the perjury trap set by Arnold Amaury, the hostage-taking of Toulouse’s ambassadors by Bishop Fulk, the burning of the dying woman by Bishop Raymond du Fauga, the eavesdropping on Peter Garcias, the sellout of the convert Sicard of Lunel, and the thousands upon thousands of betrayals coaxed, threatened, or tortured out of simple, pious people by more than eight decades of implacable Inquisition—Catholic orthodoxy had found in Arnold Sicre a champion of treachery.

William Bélibaste, the last of the Languedoc Perfect, was led over the Pyrenees in chains. News of his capture spread far and wide, scattering the faithful of Sant Mateu and Morella to the four winds, to be pursued for the rest of their lives. In Pamiers, Bishop Fournier was denied the pleasure of lighting the fire. The pope, ruling that Bélibaste was a native of the Corbières, ordered him tried by the episcopal tribunal of that region and punished by its secular authority. The archbishop of Narbonne combined these functions as spiritual and temporal overlord; “relaxing to the secular arm” involved nothing more than sleight of hand.

The trial, of which no record exists, must have been swift. In the autumn of 1321, an unbowed Bélibaste, the hotheaded shepherd turned homespun pastor, walked into the courtyard of the castle at Villerouge-Termenès, a village in the bald heart of the Corbières. He mounted a pile of straw, vine cuttings, and logs and was tied to a stake. A flaming torch was lowered. The last Perfect heretic of Languedoc was gone.

A

S YOU DRIVE INTO LANGUEDOC

from the north, past such cities as Avignon, Nîmes, Montpellier, and Béziers, it soon becomes obvious that something odd is afoot. Large brown signs on the highway announce,

Vous êtes en pays cathare

(Entering Cathar Country). At one spot, on the cypress-covered hills overlooking Narbonne, there stands a trio of concrete tubes, their uppermost third cut open in the shape of a helmet visor. This specimen of French autoroute art represents

les chevaliers cathares

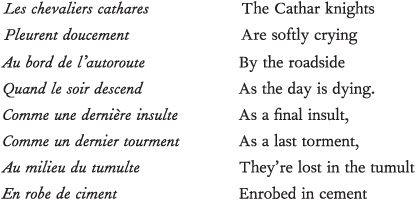

(the Cathar Knights), an Easter Island–like threesome of gigantic heretics looking impassively over the expressway as thousands of tourists, like the crusaders of yesteryear, invade Languedoc every summer. French pop singer Francis Cabrel was moved to compose a plaintive song about the sculpture in 1983:

The commemorative spirit grows more cheerful farther west, near Carcassonne. This part of Languedoc abounds with signs celebrating Cathar country. There is an official logo, a yin-yang depiction of a half-shrouded disk suggesting the light-and-dark dualism of the Cathar faith. This tourist-board branding—the logo is affixed to everything from hotel price lists to canned duck meat—seems restrained in comparison to what can be found within the walled city, which, from without, still resembles an unspoiled dream. On the main street of Carcassonne, a polyglot pitchman distributes brochures for Torture and Cartoon Museums, adding helpfully that the first is like

The Name of the Rose

and the second like

Cinderella

. Young boys with plastic swords square off on restaurant terraces. Ads for “Catharama,” a sound-and-light show held in the nearby town of Limoux, are plastered on the hoardings outside postcard shops. All over Languedoc, the word

Cathar

crops up in unusual places: on cafés, real estate agencies, adult comic books, lunch menus, and wine bottles.