The Perfect Heresy (32 page)

Read The Perfect Heresy Online

Authors: Stephen O'Shea

For once, the inquisitors were caught unawares. Or rather, they had their attention turned elsewhere, in a nasty sink of secular politics and ecclesiastical intrigue. In the years surrounding the turn of the fourteenth century, the Dominicans and their episcopal allies had at last run into resistance, as urban leaders reconciled themselves to the French conquest and royal officials began seeing the all-powerful clergy as inimical to the prosperity of the province and the prestige of their monarch. In Albi, Bishop Bernard de Castanet threw many of his secular adversaries into prison, on what were often flimsy charges of latent Cathar sympathies, and insisted that any opposition to him was tantamount

to sin. To drive home his point, Castanet began the erection of the red-brick behemoth of Ste-Cécile, the fortress cathedral which still reminds the town of the bishop’s might. In Carcassonne, plots were hatched to destroy Inquisition registers; in the hands of unscrupulous bishops and friars, these bound volumes of confession and betrayal had become tools of blackmail and extortion.

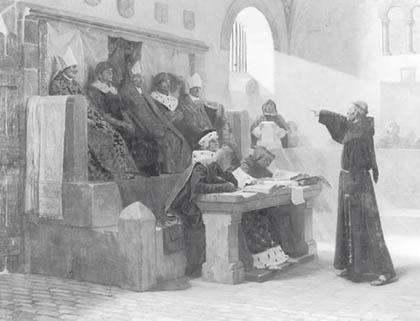

While Peter Autier quietly made his way back from Italy to the highlands of Languedoc, civic strife kept the inquisitors on the defensive. Their most eloquent critic was Bernard Délicieux, a Franciscan friar who claimed that the prosecution of a moribund faith had degenerated into an abuse of power. The darling of merchants and magistrates, Délicieux was a gifted rabble-rouser who, at the height of his power in 1303, convinced a royal official to lead a mob in storming the Inquisition’s dungeon in Carcassonne and freeing all of its prisoners. The incendiary friar, who went so far as to claim that inquisitors simply made up confessions of fictitious people in order to blackmail the innocent, stood squarely in a purist tradition that despised the Dominicans for their gradual slide into worldliness. Indeed, the brand of apocalyptic piety common to Délicieux and many others, who were known as “Spiritual Franciscans,” would be declared a heresy in 1317. They made the mistake of taking up where the Cathars had left off—in decrying too loudly the wealth of the Church. Their less radical brethren, however, weakened the appeal of heresy. Throughout the thirteenth century, the preaching and example of the friars had done much to bring spontaneous, popular piety back into the fold of orthodoxy.

Before the uproar caused by Délicieux died down, the Autier brothers had benefited from five long years of neglect. In the hills of the Sabartès, the up-country near Foix, Catharism once again took root. Although nearly three generations had passed since the time of tolerance, there were still vivid memories of the “good Christians” who had once freely walked the mountain meadows and preached in village squares. In the first decade of the new century, Peter Autier recruited about a dozen people to join him in his austere mission, among them the last recorded female Perfect, Aude Bourrel. There were to be no Cathar “homes” or bishops or mountaintops this time around. The acolytes of Autier led a harsh life of perpetual stealth and moonlight travel, always on the move lest they be detected.

Bernard Délicieux as depicted by Jean-Paul Laurens

(Musée des Augustins, Toulouse/Art Resource, New York)

The 1,000 or so households won back to the illicit faith stood in constant peril of betrayal; if but one of their family turned traitor and went to the authorities in Toulouse, Carcassonne, or Foix, misery and ruin would have ensued. There were instances

of husbands and wives concealing their heretical beliefs from each other, of village gossips ignorant of the dualist missionaries hidden in their neighbors’ back rooms, of suspected double agents for the Inquisition found murdered in remote ravines. The credentes spoke guardedly of their faith in coded language: The “scandal” referred to the decades of persecution; the “understanding of the Good” (

entendement de Be

), to their acceptance of the Perfects’ message. Unlike their predecessors of a century before, conversant with troubadour, tradesman, and merchant, the Cathars of 1300 lived in a lonely landscape of fear.

The nature of the revival reflected the sadly reduced circumstances of Catharism. Autier’s Perfect were metaphysical highwaymen, dimly glimpsed creatures of the night who acted less as pastors of a flock than as visiting angels of death. Administering the consolamentum to the dying became the raison d’être of the Perfect. Credentes had always wanted to “make a good end” so that their next “tunic,” or earthly incarnation, would lead them closer to God. Among Autier and his followers, however, the consolamentum at death’s door took precedence over other aspects of the faith.

The risks taken to attend to the expiring were immense. Time was short, making subterfuge all the more difficult. Panting messengers sought out the Perfect, or people who knew where they were hiding, then led them back, often over great distances, to the grieving family. Since medieval death, like medieval life, entailed a promiscuous lack of privacy, the Perfect had few occasions to be alone with the dying and perform the sacrament. They frequently spent hours, if not days, concealed in a household, hoping that the stricken believer would not lose consciousness before they had a chance to promote him to a better future life. In one instance, having advised a relative to

find a pretext for clearing the sickroom of its milling guests, Peter Autier donned the clothes of the future widow and took care to keep his back to the window as he administered the consolamentum. Those who might linger on for several days were ordered to undertake the

endura

, a hunger strike that ended in death. Nothing could be allowed to corrupt—and thus cancel—the otherworldly grace bestowed by the consolamentum, and the Perfect, for safety’s sake, could not risk staying around to keep a vigil over the ill. The endura was a cruel surrogate for the hospice work performed by Cathar Perfect in happier times.

Peter Autier’s men must have realized that their obsession with the final consolamentum might give simple credentes a skewed vision of what was a philosophy that embraced all of life. Errors about the faith could flourish. Grazida Lizier, a woman believer from the village of Montaillou, gave the following strange version of dualism to the Inquisition: “I believe God made those things that are helpful to man, and useful too for the created world—such as human beings, the animals men eat or are carried about on—for instance oxen, sheep, goats, horses, mules—and the edible fruits of the earth and of trees. But I don’t think God made wolves, flies, mosquitoes, and such things as are harmful to man.” Other credentes strayed from Cathar precepts by squirreling away scraps of bread touched by the Perfect, a practice similar to orthodoxy’s reverence for relics. Earlier Cathar leaders might have denounced such material magic, but Autier and his fellows blessed the bread crumbs as a souvenir of their passage.

Discovery was inevitable, for thousands of people—especially a grudge-bearing, garrulous peasantry—could not be expected to keep a secret indefinitely. Also, after the middle of the first decade of the fourteenth century, men of exceptional

ability were appointed to head the Inquisition. Geoffrey d’Ablis, an incorruptible Dominican, got Carcassonne; Bernard Gui, a brilliant investigator, Toulouse. In the county of Foix, Jacques Fournier, the bishop of the see of Pamiers, undertook an Inquisition that was a model of painstaking thoroughness. Fournier, an intelligent and sensitive Cistercian who would later be elected Pope Benedict XII, brought what can only be termed an anthropological curiosity to bear on the practices and prejudices of the remaining Cathars—to the delight of future historians. He and Gui were not vindictive hacks; both men allowed Christian ideals to inform their work. Many of their hundreds of victims appealed for, and received, clemency. To the Perfect and the unrepentant credentes, of course, the inquisitors showed no mercy.

The Autier network began unraveling in 1305, as the result of a betrayal. The turncoat was one William-Peter Cavaillé, a longtime believer who had kept his mouth admirably shut while serving time in the prison of Carcassonne. Upon his release, he badgered his fellow credentes to lend him a petty sum of money so that he could dispose of a debt he had contracted with a jail guard. For reasons unknown, the money was denied, and Cavaille, furious, took his revenge by putting the inquisitors onto the scent of the secret revival. Through his efforts, in September 1305, two Perfect were captured and a manhunt begun. The next five years saw the Perfect of Peter Autier’s revival—Peter Raymond, Amiel de Perles, William Autier, James Autier, Prades Tavernier, Philip d’Alayrac, Pons Bayle, Peter Sans, Raymond Fabre—picked off and sent to the stake. One of them, Sans Mercadier, committed suicide in despair.

Unprecedented police actions marked the investigation, such as the raid of September 8, 1309, when the village of Montaillou was sealed off by soldiers and all of its inhabitants were arrested

by the inquisitor Geoffrey d’Ablis. Although d’Ablis, detecting a recrudescence of the forbidden faith, imprisoned many of the villagers, it would take a far more skillful questioner, Jacques Fournier, to find out a decade or so later that Montaillou had been that rare pearl—a settlement where the heretics formed a majority. Fournier also discovered that its randy priest, Peter Clergue, had wheedled many village women into his bed through a peculiar interpretation of Catharism that called for carnal adventures with the Catholic clergy. Clearly, not all adepts of dualism shared the stern piety of the Perfect.

In the summer of 1309, the elusive Peter Autier was finally caught. Precisely 100 years had passed since the armies of the north marched on Béziers and Carcassonne to begin the extermination of the Cathars. Unfortunately, the transcripts of the interrogations Autier withstood—he was held for nearly ten months—have been lost to posterity. In April 1310, the inquisitors hauled him up in front of the cathedral of St. Stephen in Toulouse and burned him alive. His last wish, which he reportedly cried out as he was being tied to the stake, was to be given a chance to preach to the huge crowd of onlookers. In no time, Peter Autier declared defiantly, he would convert them all. The request was denied.

Bélibaste

T

HERE WAS NOW ONE

C

ATHAR LEFT

in Languedoc. One Perfect in the long line that stretched back through the Inquisitions of Fournier and Gui, the wars of Raymond and Louis, the crusades of Innocent and Simon de Montfort, the debates of Dominic and Guilhabert, and the Cathar International of Nicetas and Mark—the last man in a procession of holy men and women that began, the Cathars believed, in the time of Mary Magdalene and the twelve apostles. His name was William Bélibaste.

As befitted his singular status, Bélibaste was perhaps the most peculiar Perfect in Cathar history. A murderer and adulterer, he nonetheless proved a gentle pastor to his small following of credentes and, when his time came, showed as much courage as his far worthier predecessors. It was the sinner, not the saint, who bade good-bye to the greatest heresy of the Middle Ages.

Believers in the “good men,” the Bélibastes were a clan of

landowners in the Corbières, the rugged upland that overlooks the valley of the River Aude. William, one of several brothers, spent his early manhood as a shepherd, wandering the windswept reaches of southern Languedoc with his flock, following the paths of transhumance that had been traced through the mountain passes in antiquity. His descent from the high pastures in the autumn of 1306 had changed his life forever—in the course of a brawl, Bélibaste beat another shepherd to death. Having become notorious throughout the Corbières, he ran from the French king’s justice, taking with him a brother who was sought by the Inquisition. The two fugitives eventually came across others hiding in the hills: the hunted Perfect of the Autier revival.

One of them, Philip d’Alayrac, befriended the remorseful shepherd. Recognizing a promising recruit, the Perfect began initiating the murderer into the arcana of the dualist faith. Belibaste’s sin was washed away when, after several seasons of instruction, he was given the consolamentum. Whether he intended to be an active missionary or simply wished to atone for his wrongdoing will never be known. What is certain is that he and d’Alayrac, arrested on suspicion of Catharism, somehow escaped from the prisons of Carcassonne in 1309 and fled over the Pyrenees to Catalonia. When d’Alayrac ventured northward on a mission of mercy the following year, he was captured and burned, leaving Bélibaste alone in Catalonia to comfort the refugees who had deserted Montaillou, Ax-les-Thermes, and other towns in the Sabartès to escape the inquisitors. The former shepherd now had a small flock of souls.