The Physics of Sorrow (20 page)

Read The Physics of Sorrow Online

Authors: Translated from the Bulgarian by Angela Rodel Georgi Gospodinov

They are afraid of sparkling reflections, dangling chains, moving people or equipment, shadows or dripping water. (

Shadows or dripping water . . . that’s almost poetry, no, it’s a cave.

)

CHAPTER 7

: Slaughter of Livestock

Preparing livestock for slaughter

Animals injured during transport or not yet weaned should be slaughtered immediately (

out of compassion

), but if this is impossible, then no later than two hours after being unloaded. (

Because the quality of the meat decreases, following the logic of suffering = bad taste.

) Animals incapable of walking should be slaughtered on the spot or conveyed by cart or platform to the proper place for immediate slaughter. When ready for slaughter, animals should be driven to the stunning area in a quiet and orderly manner without undue fuss and noise . . .

There are three main technologies used to effect stunning: Percussion, Electrical Shock, and Gas . . .

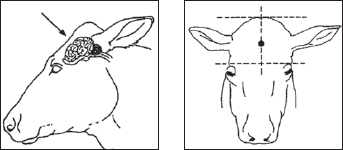

The most widely used method for stunning is the captive bolt gun. This method works on the principle of a gun and fires a blank cartridge and it propels a short bolt (metal rod) from the barrel. The bolt penetrates the skull bone and produces concussion by damaging the brain or increasing intracranial pressure, causing bruising of the brain. The captive bolt is perhaps the most versatile stunning instrument as it is suitable for use on cattle, pigs, sheep and goats as well as horses and camels, and can be used anywhere in the world . . .

Bulls: place the gun firmly against the forehead at a right angle 1 cm to the side of an imaginary line connecting the top of the head and a straight line between the eyes. (

What mathematics of death, what geometry of murder . . .

)

Calves: the gun should be placed slightly lower than with adult cows, since in calves the upper part of the brain is still underdeveloped. (

Man really has thought of everything

)

Fig.51. The correct positioning of a stunning gun.

(From “Guidelines for Humane Handling, Transport and Slaughter of Livestock” in accordance with the European Convention for the Protection of Animals for Slaughter.)

Now that’s what I call an innocent, hygienic text, as cold and aseptic as the tiles of a slaughterhouse—washed sparkling clean once the job is done.

No animal would do that.

T

HE

M

INOTAUR’S

D

REAM

I dream that I’m beautiful. Not exactly beautiful, but inconspicuous. That’s what it means to be beautiful, to be like everyone else. My head feels light. My eyes are on the front of my face. I have a nose, rather than nostrils. I have human skin, thin human skin. I walk down the street and no one notices me. Now that’s happiness—no one noticing me. It’s a happy dream.

I walk slowly, avoiding the people coming toward me at first, I keep to the very edge of the sidewalk, near the walls of the houses. But a miracle has occurred. No one rushes to get away from me, no one screams in horror that they’ve seen a monster, children don’t

cower behind their mothers, the old folks don’t cross themselves, the men don’t draw their swords. I’m walking down the street. It’s light out. I haven’t seen this much light since I was born. One woman accidentally bumps into me. I’m afraid she’ll scream. She turns around, looks at me from very close up . . . she doesn’t recognize me . . . she doesn’t scream . . . she smiles . . . and apologizes. No one has ever apologized to me before.

I see people sitting on benches. I sit down, too. Alone. I watch what the people are doing and do the same thing.

They sit and watch other people.

I sit and watch other people.

Then dusk starts to fall. I hear one little boy telling his father: dad, let’s go home, it’s getting dark. The words “dark” and “home” are the first worrisome thing in the whole dream up until now. The dark has always been my home, but now I feel homeless. For the first time I get scared that I’m lost. Which is ridiculous, since I have never gotten lost, I come from the Labyrinth, after all. And the more my fear grows, the more I shrink. A tall man leans down over me, grasps me with his large hand (I notice he’s not holding a sword), and asks me if I’m lost and whether I know my address. I keep silent. And where is mommy, the man asks, can you tell me where mommy went? He shouldn’t have asked that question. I can feel my jaw elongating, my skull growing heavy and hard, but I don’t want to hurt him. Thankfully the dream is coming to an end, since the situation is getting pretty desperate. That’s the moment in which dreams tear apart.

I woke up in the dark in my usual home. That was my happiest dream. One day with people whom I didn’t kill, who didn’t kill me, who didn’t even notice me. There was no bad blood between them and me. I presume that people don’t have those sorts of dreams. In their dreams, they wander through dark labyrinths and battle Minotaurs.

I

RREVOCABLE

From time to time I emerge from my refuge and go to Odeon, the art-house movie theater in town. Old black-and-white films are the only thing I feel like watching. I had read that they were showing a Dziga Vertov panorama and I didn’t want to miss that. It was a cold January afternoon, dingy and slushy. As it turned out, five minutes before the film was supposed to start, there were no other takers. They could hardly be expected to show it just for me. Then I noticed two bums loitering around outside, shifting their weight from one foot to the other and smoking. I asked them if they wanted to come inside and watch a film and warm up. They looked at me mistrustfully, like people who were not used to getting such offers. One asked what film. I told them it was a classic, and he nodded, stubbed out his cigarette, and the two of them went in with me. I bought three tickets. The usher looked at us with the contempt of a full-blooded Aryan, but she didn’t dare turn them away. As we went in, I glimpsed how they surreptitiously straightened up their coats and took off their winter hats. They settled into the back row, it was warm in the theater and from what I could tell they blissfully dozed off shortly after the opening credits. It was a silent film and the theater had hired a pianist to accompany the film just as during the 1920s.

An enthusiastic camera, still intoxicated by its own possibilities, climbs over the rooftops, changes angles, lies down on the train tracks. The whole madhouse of 1920s Russia, the drunks, the Pioneers, the bums on benches. And now comes the reason why I’m telling this story—a report about a slaughterhouse. The routine slaughter of a cow, and its subsequent “resurrection” through playing the film backward. The title appears: “Twenty minutes ago, this meat was a cow.” It’s as if the camera is calling: “Lazarus, come out!” And the sliced up pieces of meat turn back into an animal, beef turns back into cow. The intestines slip back into its belly, the steaks

plaster its haunches . . . “And now we’ll put on the skin.” And it’s as if the butchers’ knives have become thick sewing needles, while they themselves are the tailors, dressing it in the skin, which they had stripped off only moments before, they scurry about, ridiculous in their backward movement. Even the pianist’s music speeds up, the key somehow more major.

“And now we’ll bring the cow back to life”—the title on the screen announces. And here, where you expect the culmination, the miracle, the “Ode to Joy” (the pianist’s hands dash over the keyboard), instead we’re in for a shock. The cow’s death throes, rewound, remain death throes. That moment of dying, the electrical shock, the detuning of the body, the horror, the adrenaline, the whites of the cow’s eyes, played backward only intensify the mortal agony, rather than bringing it back to life, as the cameraman had expected. And despite the fact that only seconds later the cow stupidly flicks its tail, it is nevertheless clear to you: the cow is irrevocably dead.

On my way out of the theater, I have to bring back from dreamland the two blissful bums, who have missed the incorrigible death of a cow.

Every year, 1.6 billion cows, sheep, and pigs, as well as 22.5 billion birds are slaughtered by humans for food. We are hell for animals, the animals’ apocalypse.

A T

ALE OF THE

V

EGETARIAN

M

AN

-E

ATER

“Once upon a time, there was a man-eater who was a vegetarian.”

“What’s a vegetarian?

“A person who doesn’t eat meat. Like you and me.”

“And is a man-eater a person?

“Wellll . . . yeah, it looks like a person, but it’s even scarier.”

“Stop scaring the boy with your nonsense!” A woman’s voice comes from the room next door.

“Mom, I want to hear the story about the vegetarian man-eater. Should I shut the door?”

“Shut the door, so we don’t scare mom.”

“But people are made of meat, right?”

“Yes, we’re made of meat.”

“So that poor vegetarian man-eater must’ve been dying of hunger.”

“He wasn’t only dying of hunger, but from putdowns, too.”

“Wait, can you really die from putdowns?”

“Putdowns are the deadliest thing of all. All the man-eaters were making fun of him, calling him a fruit-eater and grass-grazer. Nobody wanted to talk to him. Because if you didn’t eat people, you didn’t have anything to tell your fellow man-eaters. And they were telling funny stories . . .”

“Scary . . .”

“Stories that are scary for men, but funny for man-eaters. Each would tell a tale more outrageous than the last and they’d bust a gut laughing . . . Meanwhile, our vegetarian man-eater just stood off to the side and didn’t have any stories to tell. If he happened to go over to the group of real man-eaters, they would rib him mercilessly: hey, why don’t you tell us how you battled three raspberry bushes and came back home all bloody. That kind of stuff. Or how many cabbages can you behead at once? And the poor vegetarian man-eater would slink off with his tail between his legs . . .”

“So they have tails?”

“That’s just a saying. Then one lady man-eater, who was secretly in love with our man . . . with our man-eater, she went over to him and told him that he should try people meat at least once in his life, he might like it and get himself straightened out. And he’d best try precisely with a vegetarian . . .”

“Dinner’s ready,” my mother says, standing in the doorway.

O

N THE

E

ATING OF

F

LESH

My father is a vegetarian. And a veterinarian. He simply does not eat his patients. I can see it now, how the waiters look at him when he orders some meatless dish. Just as the man-eaters looked at the vegetarian man-eater. I can still remember how one of our neighbors was always grilling him about why he refused to eat meat, had somebody been putting him up to it, had he joined a cult by chance, had he read something, how is it that everyone eats meat, but he’s broken away from the collective, if you get what I’m saying? Come on now, man up, order a trio of sausages with a side of beans, or baked kidney pie or lamb’s head. As for me, he’d say, when I grab that head, I first open up its mouth nice and wide and pull out that little tongue, mmm, then I split that little skull right open with a knife and, then, you slurp out the brains with a spoon! To say nothing of those yummy little eyeballs . . . Here my father would get up suddenly and say he had to go outside, I would run after him to puke in the bathroom. Just take that little lamb, it only eats grass, why don’t you start with that . . . the neighbor would call after him.

Funny that socialism and vegetarianism don’t go together. Like yogurt and fish.

We know that where the neighbor has been, the police are sure to follow. My father was prepared and when they called him down to the precinct, he explained to them in detail how the human anatomy was adapted to a vegetarian diet—a long gastro-intestinal tract, six times longer than the human body, unlike carnivores, whose tracts were only three times longer; flat molars, alkaline saliva and so on. He even quoted Plutarch and his essay “On the Eating of Flesh” to them, where it is said (he had copied this out in his notebook): “But if you will contend that yourself was born to an inclination to such food as you have now a mind to eat, do you then yourself kill what

you would eat. But do it yourself, without the help of a chopping-knife, mallet, or axe.”