The Physics of Sorrow (30 page)

Read The Physics of Sorrow Online

Authors: Translated from the Bulgarian by Angela Rodel Georgi Gospodinov

Sorrow makes bones brittle . . .

I have an almost cinematographic memory of being wheeled to the operating room. I’m lying on a moving stretcher and the long fluorescent lights above my head frame the empty shots of the film reel. I think to myself that if the stretcher were travelling at a speed of

twenty-four frames per second, it would start some film rolling that is now invisible to me. The corridor is empty and echoes slightly. We pass through a floor that has a small café. A mother in a hospital gown and robe and three little girls, whom the father has clearly brought for a visit, are eating cake and drinking juice. I remember every movement in slow motion. I must look frightening, with my leg elevated, a slightly soaked bandage, an IV. The three little girls stop chattering, I hear the sounds of forks dropped onto plates as they innocently turn their heads in my direction as I pass by. I try to smile, the three little girls with pink shirts, straws, juice, their vague sympathy, mixed with curiosity and a bit of fear . . . The mother says something and the three of them immediately, albeit with displeasure, turn their heads away from the passing stretcher carrying some bandaged up thing. I hold this frame in my mind while the anesthesia overtakes me. You never know what your last vision before you cross over might be.

I open my eyes a crack and see the slightly blurry silhouette of Ritva, who immediately livens up when she notices I’m awake. She has stood by my bedside for hours. Once upon a time, back in distant 1968, she had been in Bulgaria for seven days. The best seven days of my life, she always says. I was twenty—young, leftist, and in love. Those three things never came together for me again, Ritva says. We must paint a strange picture for the doctors. A woman of sixty and an immobilized man of forty. The only thing we have in common is a year—1968. The year when she was happy is the year I was born. Without a visible connection between the two events.

What worries me most at the moment is a terrifying hypothesis. I can’t raise my head to look. So I try to move my leg. Nothing happens. I can’t feel anything from the waist down. Suddenly I imagine that the sheet there is empty. I feel myself falling back into that

thick milky whiteness I had just swum out of. When I swim out of it again, it is because of a searing pain. My eyes jerk open. Ritva is again standing by me, I tell her it hurts, she calls Nurse Painkiller. I gradually realize that the pain is coming from my leg, so it must be there in its place and I can even move it. It hurts, thank God. It’s there and it hurts.

A week or two later, a cast-encased survivor, I’m lying at home, physically feeling the hours and minutes. I lie there throughout the summer of that year, serving it out like a prison sentence, without knowing for sure what crime I’ve committed. But that’s what all convicts say.

Triple fracture to the left ankle, two plates, seven pins, two cracked ribs, again on the left side. I stare at the ceiling for hours, the recumbent one’s only sky, and remember all the ceilings I’ve lain beneath. The high one in Berlin and the low one of my childhood. The constellations of flies on it. The bare light bulb wrapped in newspaper, that sole lampshade.

I recall the endless afternoons with which we were so generously endowed in that “once upon a time” of childhood, when I would again lie with my eyes open and stare up fixedly until the barely visible cracks and bumps in the ceiling started to change into strange mountains and seas upon which I set sail to distant lands. A few years later, the mountains and seas would magically transform into female hips, thighs, breasts, and curves. The more uneven and imperfect the surface, the more ships and women it hid.

And thus my journeys naturally came to an end . . . I returned to the saddest place in the world, shattered. All that remained from several years of hotels, airports and train stations were a couple of notebooks filled with hastily jotted impressions. Now, as I page through them distractedly to kill time, I finally realize it—melancholy is

slowly swamping the world . . . Time has somehow gotten stuck and autumn doesn’t want to give way, every season is autumn. Global autumn . . . Traveling doesn’t cure sorrow, either. I need to look for something else.

The saddest place

is

the world.

1

Peyo Yavorov, the most famous Bulgarian poet from the early twentieth-century, whose short and turbulent marriage ended in their double suicide, 1913-1914.

AN ELEMENTARY PHYSICS OF SORROW

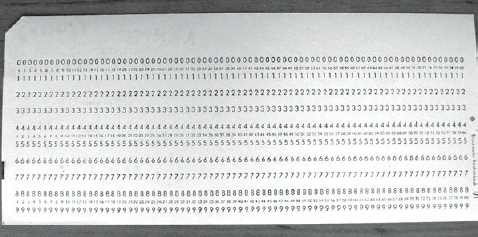

These notes are stored on old punch cards from the dawn of electronic computing devices, which have long since fallen out of use.

Q

UANTA OF

E

QUIVOCATION

One of the most mindboggling things in the physics of elementary particles is how important the very act of observation is on their behavior. According to the Copenhagen interpretation, as early as the 1920s quanta act like particles only when we observe them. The rest of the time, hidden from our gaze, they are part of a scattered and supposedly disinterested wave, in which we don’t know exactly what’s going on. Everything there is possible, unforeseeable and variable. But once they sense we’re watching them, they instantaneously start acting as we expect them to, orderly and logically.

The world is the way we know it to be from the old textbooks only because (or when) it is under observation. Or as Idlis, Whitrow, and Dicke put it in the mid-twentieth century, “in order for the Universe to exist, it was necessary for observers to appear at some stage.” I’m watched, therefore I am.

OK, fine, but if no one’s watching me, do I still exist? I live alone, no one comes over, no one calls. On the other hand, there’s always one big invisible observer, an eye we should never forget. The Old One, as Einstein called him. Maybe that’s precisely what quantum physics or metaphysics is telling us. If we exist, that means we’re being watched. There is something or someone that never lets us out of its sight. Death comes when that thing stops watching us, when it turns away from us.

The world behind our backs is some kind of undefined quantum soup, says a Stanford physicist—but the second you turn around, it freezes into reality. I like that definition and never turn around too abruptly. I think about that teacher from kindergarten who threatened to pour my soup down my back if I didn’t eat it all. Then I would’ve found out what quantum reality is.

I write in the first person to make sure that I’m still alive.

I write in the third person to make sure that I’m not just a projection of my own self, that I’m three-dimensional and have a body. Sometimes I nudge a glass and note with satisfaction that it falls and breaks. So I do still exist and cause consequences.

If no one is watching me, then I’ll have to watch myself, so as not to turn into quantum soup.

Someone must constantly be watching and thinking about the world so that it exists. Or someone needs to be watching and thinking about the one who is watching and thinking about the world . . . Crazy stuff. Can I take on that round-the-clock duty?

The physics of elementary particles rehabilitates randomness and uncertainty. Now that’s why I love it. Whereas Einstein himself was horrified precisely by this and grumbled in his letters: “The theory says a lot, but does not really bring us any closer to the secret of the ‘Old One.’ I, at any rate, am convinced that He does not throw dice.” I, at any rate, am convinced that the Old One—just like the local geezers who spend their afternoons playing backgammon—nevertheless loves throwing dice.

One remark. Quantum physics—perhaps so as not to turn entirely into metaphysics—avoids delving into the question of who that observer could be in order to have such a status. Are we including anything here but the eye of God? Does the eye of man count as capable of maintaining the world? Does the eye of a snail, a cat, or a violet figure in the equation?

Well, we mustn’t forget, after all, that quantum physics explains things on the micro-level. But how can we be sure that God isn’t an elementary particle? It’s quite likely that he’s a proton, electron, or

even a boson. God is a boson. It sounds nice. It sounds like God is a bison, Aya would say.

However, He’s most likely a photon—which has a dual nature like all quanta, but a rest mass of absolute zero. And that’s why it can move at the speed of light. When we say that God is light, we don’t even realize how deeply we’ve gotten into quantum physics. Or else he’s a neutrino, maybe even faster than light and capable of unexpected transformations. That which the old Evangelists/physicists described as the Transfiguration of the Lord was a transformation of the neutrino. But I still would like Him to be an ant, a turtle, or a

Ginkgo biloba

tree.

That which has not been told, just like that which has not happened—because they’re of the same order—possesses all possibilities, countless variations on how they could happen or be told.

Alas, the story is linear and you have to get rid of the detours every time, wall up the side corridors. The classical narrative is an annulling of the possibilities that rain down on you from all sides. Before you fix its boundaries, the world is full of parallel versions and corridors. All possible outcomes potter about only in hesitation and indecisiveness. And quantum physics, filled with indeterminacy and uncertainty, has proved this.

I try to leave space for other versions to happen, cavities in the story, more corridors, voices and rooms, unclosed-off stories, as well as secrets that we will not pry into . . . And there, where the story’s sin was not avoided, hopefully uncertainty was with us.

A Q

UESTION FROM THE

Q

UANTUM

P

HYSICS OF

R

EADING

Has anyone ever developed a quantum physics of literature? If there, too, the lack of an observer presupposes all manner of combinations,

just imagine what kind of carnival is raging among the elementary particles of the novel. What on earth is happening between its covers when no one is reading it? Now there are questions that deserve some thought.

E

XPERIMENTS

That popular experiment with the electron, in which it acts like a wave and passes through two openings at the same time, gives certain grounds for believing that it is possible to be in different places at the same time. But, as the Gaustine in me notes, we’re not talking about electrons weighing 180 lbs. and standing 6’2”. (If this were so, my grandfather would have stayed in both villages—the Hungarian and the Bulgarian one, bringing up both of his sons, living out both of his lives . . .)

Luckily, the things I’m concerned with have no weight. The past, sorrow, literature—only these three weightless whales interest me. But quantum physics and the natural sciences have turned their backs on them. If Aristotle had known that the formal division of physics and metaphysics would definitively and artificially partition the universe of knowledge, he surely would have burned his work himself. Or at least he would have combined the parts of it.

A while back, under one of my pen names, I published a novel based on the atomism of Leuccipus of Miletus and Democritus of Abdera. Ultimately, it turns out that they discovered quanta way back in the fifth century BC. Lots of time needed to pass for everything to be forgotten. I liked those pre-Socratics, those first quantum physicists, who coolly and boldly painted a picture of a world made only of atoms and emptiness. Endless emptiness and countless atoms floating around in it. I wanted to transfer the model of atomism to

literature and to discover whether the encounter between individual atoms of classic literature would produce new matter for the novel.

An atomic novel of opening lines floating in the void.