The Physics of Sorrow (31 page)

Read The Physics of Sorrow Online

Authors: Translated from the Bulgarian by Angela Rodel Georgi Gospodinov

This was a wholly serious experiment, but it was taken more as a postmodernist joke, grasped in terms of its metaphorics rather than its physics. Physicists don’t read novels. Which disappointed me greatly and caused me to withdraw from publishing for a decade or so.

Here’s what I’m interested in now. Can going back in time by recalling everything down to the last detail, with all senses engaged, bring about a critical point? Can it flip some switch and cause the whole machinery of the Universe to start going backward? It’s on the edge in any case, so the only redemptive move is backward. Minute by minute, during this hour everything that was an hour ago will happen. The entirety of today is replaced by yesterday, yesterday by the day before, and so on and so forth further and further back, we slowly step away from the edge with a creak. I don’t know whether we can meddle in those impending past days. We’ll have to relive our prior failures and depressions, but also a few happy minutes among them. There’s no getting around . . .

. . . the new injustice of death. Those, who at the moment of the reversal had already lived eighty years, will live another eighty, backward. Those who had lived not as long, say thirty, forty, or fifty years, will have to be satisfied with that same amount. But let’s note that they will be heading toward their own youth and childhood. Ever happier at the end of their lives, ever younger, ever more adored. Happily wobbling on their unsteady little toddler’s feet, having forgotten language, cooing and gurgling, until the day comes

for them to go back home. Thus, I, born on January 1, 1968, will be able to die again on January 1, 1968. That’s what I call complete universal harmony. To die the hour and minute you were born, after passing through your whole life twice. From one end to the other and back again.

G. G.

January 1, 1968—January 1, 1968

Lived happily for 150 years.

(Everyone can insert their own name and date here.)

They claim that life arose on earth three billion years ago. With this mechanism, we can guarantee at least three billion more years of life. If someone else has a better offer, then be my guest.

Another gravity is pressing in on us, one not found in classical physics, one which must be overcome, the gravity of time. That gravitational delay, which Einstein described back in 1915, doesn’t work for me. In 1976 NASA confirmed that in the microgravity of space, time really does slow down a teeny bit, and this gave rise to the legend that people don’t age in space. The myth of eternal youth was again on its way to being revived. A dozen or so aging millionaire matrons must’ve glanced up at the sky as if toward an eternal sanatorium, calculating how much a stay there with their beloved fox terriers would cost, because what’s . . .

. . . the point of being young if your pooch is pushing up daisies? This legend even reached us, I remember it vaguely, but being all of eight years old I hardly paid any attention to it. In 2010, they actually measured that time lapse with an interferometer. Yes, there

was a slowing of the cesium atom (that’s what they used), but it was insignificantly small—over a few billion years there’s a delay of a hundredth of a second. Those who had hoped to stay forever young in 1976 surely hadn’t lived to see this highly disappointing result.

My goal isn’t to slow time by a few hundredths of a second over a billion years, which I don’t have at my disposal in any case. And not in outer space, which I have no particular soft spot for (even the bus makes me car sick). I want to bring back a slice of the past, a pint of drained-away time right here, within the confines of one insultingly short human life.

N

EW

E

XPERIMENTS

I practice concentrated and close “observation.” I realized relatively early on that the shorter the time period I want to recreate (replicate), the better my chances. I gave up on the idea of my whole childhood. For some time I tried one chosen year. To remember that year in detail, to reconstruct it personally and historically, leaving nothing out.

I picked the year of my birth, because the infant has a more limited and pure world, which in that sense is easier to reconstruct, with fewer extraneous noises. So here’s the new 1968. By happy coincidence, I was born in its first days, so the two stories, mine, small and piss-soaked, and its, grand (and also piss-soaked), could unfold in parallel. The wet cloth diapers, the January cold, my mother’s warm skin, the first signs of spring in the Latin Quarter, nighttime colic, summer in Prague, the international youth festival in Sofia, “brotherly” troops in Czechoslovakia, first tooth . . . Everything was important. After a few months I was lying on the floor exhausted,

crushed by the world’s entropy. I realized that it was beyond my strength and stamina to build—as if from matchboxes—a year in its real dimensions with all of its scents, sounds, cats, rain, and newsworthy events. I’ve kept the draft of that failed experiment.

I need to narrow the range of the experiment. I decided on a month from another year, August 1986, I’m eighteen, my last month of freedom, after which my mandatory military service awaits me. A month, in which you say farewell to everything for two years—actually for forever, but you don’t know that then. You let your hair grow long, you try to get to home base with your girl. Late at night, when your parents are asleep, you sneak out with a friend into the city’s empty streets, you go to the river and look at the dark windows of the panel-block apartment buildings, on the verge of yelling “Sleep tight, ya morons!” à la Holden Caulfield or whatever it was he said . . .

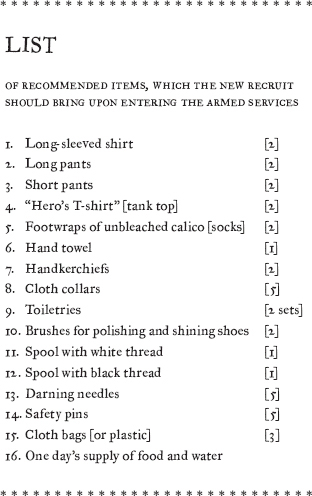

. . . but in the end you don’t do it. At the end of the month you go to the barbershop farthest away to get a buzz cut. You watch your hair falling to the floor and you try not to start bawling. You leave the barbershop already a different age, crestfallen, freaked out, sporting the hat you had prepared in advance, and you take the shortest route home. A few days later you’ll have to show up at the appointed place in some strange city—with a shaved head and a bag filled with all the things from the list of what a recruit needs. I’ve kept that list in one of the boxes.

That was more or less the month from which I needed to reconstruct every moment and sensation with all of their subtlest oscillations. It wasn’t so easy. Yes, there was fear during that month, but it was thousands of variations on fear, in some of them it looked

like a radical dose of daring. Yes, there was sorrow, but the atoms of this sorrow moved quite freely and chaotically (sorrow’s state of aggregation is gaseous) and in the best-case scenario I could only follow its twists and turns, the smoke that smoldered nearby. I lit up my first cigarettes, I now realize, to give a body to this sorrow, bluish, light-gray, vanishing. I remembered everything clearly, but I couldn’t manage to get back into that former body. What I used to be able to do—entering into different bodies and stories with the ease of a man entering his own home—now turned out to be out of reach.

E

PIPHANIES

It happened when I least expected it.

It was a late winter afternoon, the snow was melting. A few days before I completely stopped leaving the basement. I was walking ever more slowly, looking at the houses, the Sunday’s empty streets, January . . . It occurred to me, for the first time with such clarity (the clarity of the January air) that what remains are not the exceptional moments, not the events, but precisely the nothingeverhappens. Time, freed from the claim to exceptionality. Memories of afternoons, during which nothing happened. Nothing but life, in all its fullness. The faint scent of wood smoke, the droplets, the sense of solitude, the silence, the creaking of snow beneath your feet, the vague uneasiness as twilight falls, slowly and irreversibly.

Now I know. I don’t want to relive any of the so-called events from my own life—not that first event of being born, nor the last one which lies ahead, both are uncozy. Just as every arrival and departure can be uncozy. Nor do I want to relive my first day of school, my first time having fumbling sex with a girl, nor my joining the army, nor my first job, nor that ostentatious wedding reception, nothing . . . none of that would bring me joy. I would trade them all, along with a heap of photos of them, for that afternoon when I’m sitting on the warm steps in front of our house, having just woken up from my afternoon nap, I’m listening to the buzzing of the flies, I’ve dreamed about that girl again who never turns around. My grandfather moves the hose in the garden and the heavy scent of late summer flowers rises. Nothing is determined, nothing has happened to me yet. I’ve got all the time in the world ahead of me.

In the small and the insignificant—that’s where life hides, that’s where it builds its nest. Funny what things are left to twinkle in the end, the last glimmer before darkness. Not the most important

things, nor . . . there’s no way for them even to be written down or told. The sky of memory opens for that minute as dusk falls on that winter day in a distant city, when I am eighteen and have miraculously been left alone for a minute or two, crossing the army base’s enormous parade grounds. A parenthetical note for those who have never been soldiers: you’re never left with a free minute, that’s the way it’s set up. A soldier with free time on his hands is nothing but trouble, that’s what they say. I’ve trimmed the grass around the parade grounds all day with a nail clipper—those were my orders. I’ve carried stones from one pile to another. In the morning. Then in the afternoon I’ve returned the stones to their original place. At first you don’t get it, you think the world has gone mad, you don’t find that even in Kafka. But the majors don’t read Kafka, to say nothing of the sergeants. You’ve come here directly from literature, you’re carrying Proust in your gasmask bag. Hey, Proust, get over here double-quick! Hit the ground! Twenty push-ups!

Anyway, that moment when I was left alone on the enormous parade grounds under an empty sky, amid the cold air saturated with the first scent of winter, of wood and coal smoke sneaking in from the nearby village, the falling dusk and anticipations, alone for the first time, somewhere else for the first time, slight cold fear, cold clouds. And precisely that meeting of hopelessness and anticipation (my year in the army had only just begun), mixed with an endless sky, strange and beautiful, beautiful in a strange way, made that minute eternal. I knew that it couldn’t be retold.

Of course, I could list off several other golden camels in the endless caravan of minutes, three or four, not more, but I’ll try to retell only one of them. Late summer, I’m standing in front of the house, the sunset is endless in those flat places, I’m six, the cows are coming down the road, first you hear their slow bells, the shepherd’s calls,

the mooing to announce their return to their calves, the calves’ bellowed response . . . this is crying, I know it even then. Like the bawling cry that always escapes from me the minute my mother comes back from the city at the end of the week to see me. Relief and accusation are never closer together than in that crying. As close as the crying of a calf and the crying of a child when they have been abandoned for a day or weeks. I missed you so much, I’m so mad at you. I’ll never forgive you, cows and mothers . . .

In that minute, the memory is so clear even now, in that minute so densely packed with sounds, cows, and scents, suddenly everything disappears, a strip slices the horizon at its most distant point, time draws aside and there, at the very back of the sunset, there is a white room with high ceilings, one I’ve never seen before, with a chandelier and a piano. A girl my age is sitting at the piano with her back to me. Her light hair is tied in a pony tail, she is getting ready to play, she has raised her hands slightly, I see her pointy elbows . . . And that’s it.

I have never been happier, more whole and peaceful than in that minute, on the warm stone at the end of my sixth summer. As the years passed, I started counting the winters, as my father and grandfather did, they knew it was right for a person to go back home in the winter, during the summer there is too much work to bother with dying. I promised myself then that I would find that girl. I kept looking for her in all those places and years I passed through. No one turned to me with her face. I can feel myself giving up over time. Getting used to it. Old age is getting used to things.

M

IGRATION OF

S

ORROW

Empathy is unlocked in some people through pain, for me it happens more often through sorrow.

The physics of sorrow—initially the classical physics thereof—was the subject of my pursuits for several years. Sorrow, like gases and vapors, does not have its own shape or volume, but rather takes on the shape and volume of the container or space it occupies. Does it resemble the noble gases? Most likely not, as much as we may like the name. The noble gases are homogeneous and pure, monatomic, besides they have no color or odor. No, sorrow is not helium, krypton, argon, xenon, radon . . . It has an odor and a color. Some kind of chameleonic gas, that can take on all the colors and scents in the world, while certain colors and scents easily activate it.