The Pirate Queen (14 page)

Authors: Barbara Sjoholm

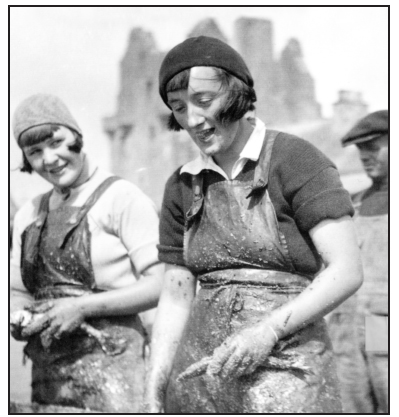

No one, in writing about the herring fishermen, the coopers, or the haulers, bothers to tell us how cheerful and high-spirited they were, so I'm suspicious that these adjectives come up so frequently, with a hint of defensiveness, in describing the herring lassies and their working conditions. All the same, it's clear from photographs and oral history that the women not only worked hard and well, but thrived on the independence of

a paycheck and the camaraderie of the wharves. Many herring girls started gutting at age fifteen or sixteen, and not a few continued to work into their sixties. Christina Jackman was a herring girl from the Shetland Islands, whose granddaughter, Susan Telford, transcribed an oral history of her life that is short on self-pity and long on laughter. Christina describes great friendship among the women, many of whom gutted herring together for years, even as they married and raised families. For some it was purely local work and only at the summer peak. Others, like Christina, worked a full season, traveling all the way down the coasts of Scotland and England to Great Yarmouth or Lowestoft, where the fishing ended in October. It was this camaraderie that enabled them to band together to demand better working conditions and wages. In the thirties, when catches began to decline and wages dropped, the women went on strike and won.

B

ILL AND

I were making our way slowly across the island to the remains of an old chapel, currently under excavation by archeologists. We saw Marion off in a field, apparently running after an errant sheep. With her bright red-and-yellow leggings, green jacket, and green jester's cap, she threw a festive splash against the somber gray sky and dull meadows. When we came to the shore, Bill pointed out a cantilevered reef that stretched out into the sea. It was the site of many a shipwreck off these coasts. He bent and picked up a religious medal, showed it to me, and replaced it carefully. He'd been here a few days ago and had found other medals. He believed the monks had made a circuit of the island's perimeter and dropped the medals at intervals in order to bless the land.

I had an instant's fantasy that Bill and I were on a CID case, looking for clues to a murder. I thought of mentioning to him that I had written some mysteries and had won a British Crime Writer's award. I had even done a reading once with P. D. James. But the fact was, I'd always been a bit of a fraud as a proper thriller writer. I never bothered to learn anything about poisons, weapons, or police procedures. As if to prove my utter ineptness as a detective, it was Bill who found all the medals.

Back at the pier, Bill and I stood waiting for Breida and Marion to catch up with us. Bill was a photographer and had restored many of the old photographs I'd seen this morning at the Fish Mart in a series of albums of Stronsay life. Years ago this bay had been so full of boats that it seemed you could walk from Papa to Whitehall. Now all you could see were a few shiny-wet seal heads, popping up from time to time to give us a curious look.

T

HE HOTEL

pub filled up in the evening. I bought Bill and Breida a drink, had my dinner, and retired upstairs to continue reading Peter Anson's classic book about Scottish fishing life. The jacket said that he joined the Anglican Benedictine community on Caldey Island when he was twenty-one, in 1910. He cofounded the Apostleship of the Sea, which still provides Catholic chaplains for ships, about ten years later, and then left the order to concentrate on drawing and writing. First published in 1930, his book already has an elegiac tone. Due to a combination of declining catches and changes in the way fish were caught and sold, many of the fishing villages he describes had lost population. Young people moved away for better opportunities; boats lay rotting on the shore. The herring fisheries, in particular, would never again reach their pre-World War II level; the industry would be finished by the 1960s, when the stocks dropped to unsustainable levels.

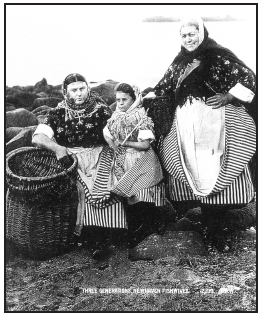

Three generations of New Haven fishwives

Yet the world Anson describes has its roots in an earlier time, when women's work was fully apparent, and partnerships between men and women still in living memory. In the coastal village of Buckie, for instance, in the late eighteenth century, Anson tells us: “[T]here was a maxim among the fisherfolk that âno man can be a fisher and want a wife.' This was literally true: without a wife a fisherman at that period would have been quite unable to carry on his job.”

An appreciation of women's important work in the fishing industry has declined precipitously since the 1700sâor even the 1930s, when Anson was describing the old ways. Anson himself saw no reason to disguise his admiration for the hardy fishwives of Newhaven and Fisherrow on the Firth of Forth near Edinburgh. These women would trek to the city several

times a week, carrying on their backs heavy creels of freshly caught fish weighing from a hundred to two hundred pounds. Sometimes the women walked in relays, shifting the basket to each other every hundred yards.

They did the work of men and had the manners of men, in addition to the strength of men. Their amusements too were masculine. They played golf long before it became the present-day fashionable sport of women. On Shrove Tuesday there was always a football match at Musselburgh between married and unmarried Fisherrow women, and it was the former who were nearly always victorious! The fishwives were famous for their rude eloquence.

There was a sound like hammers striking anvils, and the whole hotel seemed to stagger briefly. It was just the pipes. The noise downstairs in the pub went on for quite a long time, but the next morning the hotel was deserted as usual. I took a long walk along the shore in the biting wind. Arctic terns darted at the crown of my head, and sea gulls cried relentlessly. Forests of bladder wrack and tangle, like soaked shoe leather, seemed to have washed up overnight; down by the low-tide mark a rusty brown carpet of rockweed covered the stony shore. Long years ago, before the herring industry made Whitehall an Orkney boomtown, there had been a kelp factory on the island. In 1722 a local laird, James Fea, got the idea to harvest the seaweed here and burn it down to a glossy slag. Its high alkali content made the potash valuable for soap and glass manufacture. The kelp factory thrived for a hundred years, until 1830, and at its height employed three thousand workers and made a substantial profit for James Fea and the lairds who followed him. Seaweed is free, after all, and the labor of crofters was almost free as well. A few days ago, in Kirkwall, I'd found a haunting post card of an old, sepia-tinted photograph showing three women burning kelp. They are wearing old-fashioned long skirts and shawls; the land is barren; the smoke half-obscures their faces and makes them seem like ghosts beginning to materialize.

I bought a little food for lunch at the local shop, which was open only sporadically, and around midafternoon went up past several large farms to the ridge that ran along Stronsay's back like a spine and gave stunning views on either side of sand-ringed bays. Marion had suggested I talk with an elderly couple who had a small farm up here, as they might be able to give me a sense of the old Stronsay way of life.

As soon as I walked into their parlor, I felt welcomed as I hadn't been since leaving my friends in Edinburgh. My hand

was pressed, sherry was poured, homemade buttery shortbread appeared on a green glass plate. Edwin (Eddie) and Charlotte (Carrie) Cooper were in their late seventies, dignified and lively. They were remarkably good-looking people, who must have been stunners in their youth. Both had been born on the island, Eddie in this very house. Eddie's grandmother had worked as a herring girl at More's curing station; his father had worked at the fish-gutting factory. Carrie had been born right across from the Fish Mart, above what was then the post office and is now part of the Stronsay Hotel. Her first job was to take telegrams from the post office to the agents in their offices in the Fish Mart. She would dash across the busy street, avoiding boys rolling hoops and horse-drawn carts full of fish guts on their way to the factory. There were shops in every building then: sweet shops, barbers, chip shops, butchers, shooting galleries.

“In the summer,” Carrie added with a smile, “there were five ice cream shops, three of them owned by Italians. The bar in the hotel was the largest north of Inverness. There was a cinema.” That hotel burned down in 1939. Of the cinema there is no trace. “And on Sundays, oh, you can't imagine,” said Carrie. “You would hear the sound of singing all over the island. At the Stronsay Kirk, at the Salvation Army, at the missions.”

I'd read that Bible reading and churchgoing were big on Stronsay. Every summer the evangelist Harry Young would conduct “tent missions” just outside the village. It was part of the entertainment in a short summer where the work pace was fast and furious. The girls would come over on Sunday from Papa Stronsay, dressed in their finest, smelling of scent, lotion smoothed over their raw hands, carrying their Bibles. After services they would stroll and flirt, eat fish and chips, ice cream and sodas.

Carrie and Eddie plied me with more sherry. They brought out albums and scrapbooks. They had excellent memories. Carrie had kept a journal most of her life. She joked that after I left she would write down what we'd said so she'd remember it. We exchanged addresses, and then Eddie gave me a ride back to Whitehall village, taking a longer route so he could show me some of the farms. He'd left school at fourteen, and in addition to tending the small family farm, he'd delivered the island's post. Up to and all through the war he'd used a horse-drawn cart, but afterward he made his rounds by automobile. He said the fields used to be full of people working, the roads busy whatever the season. Now the island's economy was in worse shape than ever. The sons and daughters of the small farmers had moved away, the farms had been consolidated into larger concerns, and no one grew anything now but hay for the cattle. A European Union embargo on British beef had wreaked havoc on that, too. The population was down to only a few hundred. Most of the people he and Carrie had grown up with had left.

Eddie drove me slowly through Whitehall village. “There was a general shop there. And a barber there.” A cold white light had fallen over the street, as if the whole village were an underexposed print with only ghostly images visible. The photographs that Bill had restored showed prosperous men in suits standing in front of the Fish Mart, and herring lassies and coopers crowding the wharves. If only it were so simple to redevelop the original negative and see the ghost shapes fill in and the village come to life again.