The Pirate Queen (4 page)

Authors: Barbara Sjoholm

But Dónal of the Battles, as her husband was called, had a fierce temper and reckless ways that led him into trouble. He was more interested, apparently, in feuding with the neighboring Joyces than in providing leadership and income. As the years passed, Grace grew to assume authority not only over the household, but over the O'Flaherty fighting men. It's after her marriage that historical sources begin to mention her raids on ships bound for Galway. She cornered them, demanding either tribute or part of the cargo in return for allowing them further passage. Dónal, on the other hand, was eventually murdered by the Joyces, who'd nicknamed him “the Cock,” for his high-handed, posturing ways. “Cock's Castle” they came to call the island fortress on Lough Corrib that had once been a Joyce stronghold and that Dónal had taken away from them. After his death, they came to reclaim it, but found Grace O'Malley installed. She defended it so vigorously it was rechristened “Hen's Castle.” It's still called that today.

Grace defended it again from English soldiers who came to force her surrender. After days of siege she had her followers strip the lead off the castle's roof and melt it down, the better to pour over her enemies' heads. Then, when the English retreated off the island, she sent one of her men for reinforcements. Hen's Castle remained hers, at least for a time.

For although many of the traditional Brehon laws gave Gaelic women a more equal role than their counterparts in the rest of Europeâand Grace had been able to keep her maiden name and her right to O'Malley landsâGrace could not legally inherit the O'Flaherty title or lands after Dónal's murder. With no other means of support, Grace retreated home to Clare Island to, in effect, create her own independent chieftaincy. It's a measure of her charismatic leadership that a number of

disaffected O'Flaherty men chose to follow her, assuming that her skill at sea would translate into wealth and security for them. When her father died, the ships that had belonged to the O'Malleys came to her. She began to assemble a force of two hundred seafaring and fighting men, drawn from many of the clans of Western Ireland. Along with trading and the licensing of fishing rights, piracy grew more important to her, and with it, control of the passage into Clew Bay.

Piracy, which is essentially robbery, only romanticized because it involves ships at sea, has taken many forms over the centuries. In sixteenth-century England it was to some degree state sanctioned, as Elizabeth I sought to divert the gold and silver flowing from the New World to Spain away from King Philip's coffers and into her own. Sir Francis Drake and others were semi-officially hired by the crown as privateers to attack Spanish galleons. This century also saw the rise of the pirates of the Barbary Coast, who, after terrorizing Mediterranean waters, had begun to venture into the North Atlantic. Often called Turks, they were in reality mostly Algerians living under the rule of the Ottoman Empire, which stretched from Hungary to the Middle East and North Africa and whose capitol was Istanbul. During Grace's lifetime, and especially in the seventeenth century, Algiers became a great slave market, where European captives who'd been abducted from coastal villages and ships were taken to be sold or ransomed. The piracy of the Algerian corsairs was thus doubly threateningâyour money

and

your lifeâand Grace herself had to steer clear of their ships.

Her own form of piracy seems almost benign, though her victims, mainly the merchants who owned the French, Portuguese, and Spanish caravels and galleons that had a long history of trade with Galway Town, were none too happy when

they saw her ships on the horizon. Sometimes she only charged a percentage of their cargo as a tax for allowing them to pass; sometimes she took the whole cargoâand the ship to boot.

Outside my room at the lighthouse, I leaned forward into the freshening wind (the time when I'd be heartily sick of constant Atlantic blows was still before me). The captain of a ship passing off this rocky coast would hardly guess that on the other side of the island lay a pirates' lair, the harbor sheltering Grace O'Malley's growing collection of vessels: the wooden, clinker-built Gaelic galleys, with thirty oars, a single mast, and a lateen sail, whose shallow draughts, like those of the Viking longships, helped with maneuvering around Clew Bay's reefs and shoals. Stolen Mediterranean caravels and “baggage boats,” the yawls and longboats that carried fish, cattle, goods, and the spoils of plunder, lay there as well. Those sailing offshore would never imagine that a widow and mother of three had put aside domestic duties for a second chance to relive her childhood dreams of seafaring and swashbuckling.

D

INNER THAT

night was in the elegant dining room of the lighthouse. Monica's restrained service hinted that endive salad with goat cheese and spring lamb with new potatoes were a bit wasted on three Americans, two of whom were wearing T-shirts that said “Make Mine a Guinness!”

He was from Fresno; she was originally from Tennessee. He worked for the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms and had the look of someone used to smashing down doors. She had a cowed expression (I imagined) and kept on about how beautiful Ireland was, and how friendly everyone was, and how green it was, while Mr. Fresno interrogated me: What was I doing

here? How long was I planning to be gone? What did I do in America?

At first I was vague about my trip, and what I was looking for, but finally I broke down, only to recall how dreams are diminished when shared with the wrong people. I was traveling for a few months, just on my own, to collect material about women and the sea. I was a writer, in Seattle, and hoped to eventually tell some of the stories.

“What's that going to prove?” asked Mr. Fresno, his eyes skeptical, his jaw hard, while Ms. Tennessee cut her lamb into dainty pieces. She was faded underneath her makeup, an over-the-hill country singer perhaps, in her forties, wearing cowboy boots and silver hoop earrings, a ring on every finger.

“It's not to prove anything,” I said mildly. “It's just an interest.” A consuming interest, I could have added, one to have made me come all the way here.

“But you want to make a point, right?” He had the straggly hair and stubble of a man on vacation, but the bloodhound perseverance of a working detective. “Like, that a few women were sailors or something?”

“Well, there was Grace O'Malley,” said Ms. Tennessee. Her long dark hair fell in her face, and she didn't look at him as she spoke. “You know, that pirate lady they talk about. I bet that's why you came to Clare Island, isn't it?” She smiled at me, with an encouraging nod. “To learn more about that pirate lady, Grace O'Malley?”

He ignored her. “What's your methodology?” he asked.

“My methodology?” I said.

“You know, your

plan.

Are you doing interviews and tabulating results?”

Now he sounded like a dissertation committee member. In

fact, my methodology was somewhat random. I had some leads, some hunches, and boundless curiosity. Where was the fun in knowing what I would find before I set off? Did I dare mention

fun

? Or passion for the subject? I wasn't so naive as to expect to discover that women had actually been the majority of seafarers. I'd be happy if I found a few more than Grace O'Malley. In fact, I was happy with what I'd been finding out about Grace O'Malley in the last two days. Who was Mr. Fresno to disparage her? She'd skewer him with her cutlass. Fortunately Monica came in with apple tart and coffee. The conversation shifted, to lighthouses, and Monica, warming, told us the story of the renovation. I left my companions leafing through a book of photographs that showed the progress of turning the decommissioned lighthouse into an inn.

Still, after dinner as I went to my room, and laid out my journal and books, I wondered at my hesitancy. Why hadn't I made larger claims for women's connection with the sea? I was still uncertain, I supposed, what that might mean. Had we only stood on shore, waving goodbye? How many female captains, sailors, fishers could there have been? How many myths would it take to make a satisfying statistic? Instead of looking through my notes, as I'd meant to, and describing what I'd seen today, I opened the red door of my room, and went out to the thick, whitewashed wall at the cliff's edge. The sun was setting, familiarly, in the west. Even though I'd grown up on the Pacific, not the Atlantic, my travels over the years in maritime Europe had always pointed me in the direction of my childhood ocean view. The clouds had a stronger whiff of rain now, blood orange and carmine against the flame-blue sky.

It was easy for me to imagine young Grace scanning the same horizon I had when young, for, though she looked toward

what would become Canada and I toward Japan, neither country was visible; there were only waves and more waves.

The ocean off Long Beach, California, was already much tamed when I came along midcentury. There was a breakwater and a port; the shoreline had been reshaped in places and over the years much more of that would happen, as the city struggled to overcome its tawdry amusement park image and attract back those who'd fled to the suburbs. Nevertheless, to me the ocean was a vast wilderness of water, especially compared with Alamitos Bay, where I often spent summer days when I was small. The bay was the baby beach, separated from the ocean by a thin peninsula of sand, a road with houses on either side. That strip of dividing land was like a curved arm, and in the warmth of that embrace my younger brother and I spent long days splashing in the shallow waters of the bay or making sandcastles on the shore. My mother and her two good friends, Vina and Eleanor, sat under an umbrella, gossiping and keeping an eye on all us children through harlequin-tipped sunglasses.

The mothers didn't like to go to the real beach across the road. It was windier, for one thing, and a long, hot trek down to the water's edge. The waves, though subdued by the breakwater, were tall to a child. But once I reached a certain age, six perhaps, I begged relentlessly to go to the real beach, at least part of the day. I relished the cold slap of the Pacific in my face, loved to feel lifted off my feet and carried into shore by the waves. I even lovedâthough this was frightening tooâto be dragged back into the sea by a powerful force, the most powerful natural force I'd ever known.

The ocean was huge and even as a child I loved that hugeness and didn't fear it. The salt water was less a bridge than a world between worlds. If you were a fish, you could swim to

Japan. If you were a mermaid, it would be your home. But all this, my mother, raised in the Midwest, swimming and canoeing the Michigan lakes, didn't understand. The ocean for her was a closed door, the end of the road. She stood on the shore, up to her ankles, complaining that the water was freezing and she just couldn't understand how the Pacific could be so cold when it was

ninety-five

degrees in the shade, for goodness sake. She splashed her arms and legs, but not her face or hair, and returned to towel and book, with the firm injunction to me to watch my little brother, and for neither of us to go in too deep or too far.

But deep and far was just where I'd longed to go.

T

HE NEXT

morning the Americans were already gone. After breakfast I set off for a walking tour of the island. It was wet but not raining; rills and streams trickled through lumpy fields. Before the Great Famine two thousand people had lived on Clare, and these had been their potato fields. The hills and trenches were grown over now, and turf had spread over the fields, making the landscape resemble a series of rusty-green bundles placed in rows. Bright marsh marigolds were abundant, and wild yellow iris shot up from boggy rivulets. A pair of peregrine falcons soared overhead. Near the few houses along the road bloomed raspberry lipsticks of fuchsias, white-pink rhododendrons, and purple foxgloves. Clare Island had 150 inhabitants now. During the era when the O'Malleys and their retainers summered here, the land must have teemed with cows, for the Irish clans counted wealth in castles and cattle, and in her heyday Grace owned a thousand head.

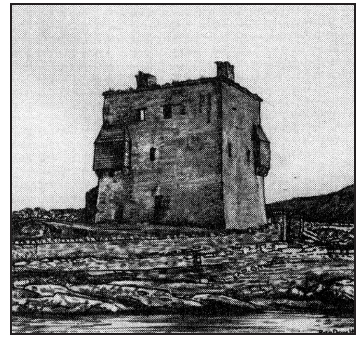

After a few hours I arrived down at the harbor and the castle. The square little fortress had looked better from the sea. Some sheep grazed outside on the grassy headland. Inside, the ground floor was dark and rubbishy with beer cans littering the dirt floor. Irish castles were originally the idea of the Norman invaders in the twelfth century; the warring Gaels continued the tradition of military strongholds in which the tower kept enemies out. These castles were the essence of romance: four or five stories high, rounded or square, with slit windows from which to shoot arrows. Some had turrets and crenellations. Family life took place upstairs, where the thick walls were kept whitewashed and hung with skins and furs to keep out the cold.