The Pirate Queen (41 page)

Authors: Barbara Sjoholm

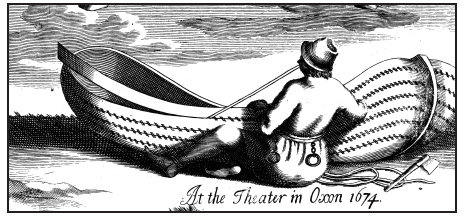

These boats carved on rock looked very much like the Inuit

umiak,

or “the woman's boat.” It was not a kayak, which is found mainly in the North American Arctic, but a large open boat. The Arctic explorer Fridtjof Nansen wrote, “By Europeans it was named the woman's boat because in contrast to the kayak, it was rowed almost exclusively by women.” The

umiak

is found over the whole Arctic, from Siberia to Greenland. Most common in the north of Norway was the Nordland boat, Hilgunn told me, as we began driving along the Efjord. That would have been the sort of boat Peder Thomassen, Beret's husband, built. The Nordland boat, clinker-built and single-masted, has remained essentially unchanged in design since Viking days. It once came in eight different sizes to accommodate everything from inshore fishing to coastal trading voyages. Smallest was the

faering

or

kjeks,

probably from the Sami word

kjaex,

meaning “woman”âthat is, a boat handled by a woman. Most traditional for Lofoten fishing was the

Ã¥ttring

or

fembøring.

Trouser-Beret had a

fembøring.

Because people often rented rather than owned land, the boat was the main piece of property to be purchased and passed down. Salten and Tysfjord supplied the whole of Lofoten with boats. The Sami who lived by the fjords had to pay a tithe of a boat to the sheriff every year.

“That's where she took her boat out,” said Hilgunn, pointing across the fjord. “There, do you see? By that waterfall. She had her mill there. The house was farther in, much farther, by a lake called Dypvann. After she got the boat out, she had to walk at least five kilometers, perhaps more, to the house.”

There's a story that in the winter of 1832 Beret decided to leave Lofoten before the fishing was over. Her crew protested; they were doing so well that year. The fish were plentiful, and the prices were good. Their protest didn't matter a bit; as skipper, Trouser-Beret made the decisions. They set sail for home a full month before the fishing was over. Early the morning of March 22, they arrived in full sail here in the Efjord,

and she steered the boat right over to the spot Hilgunn pointed out. The moment the boat touched shore, she hopped out and told the crew to deal with the boat and the gear. She was late for something, she said, and hurried up past the waterfall to her home.

Inside she lit a fire in the hearth, boiled herself up some coffee. She took out her pipe and tobacco. There was time for a well-deserved smoke. Afterward she went into the bedroom and gave birth to her fifth child.

In Lofoten, Beret and her crew, like the other Sami, wouldn't have been welcome in the fishermen's cabins, Hilgunn told me as we drove on, Sven still silent as a clam in the back. They would have lived in tents they erected themselves. But here on the Efjord, she and her husband had a boat shed, a mill, and a house inland. Beret earned the money for the lumber from her fishing and Peder built them. “Her house burned down,” said Hilgunn. “She had to build another. Oh, it was a sad story. First a man came to their farm with a weapon. Her young son Paul took hold of it. He had never seen a gun before. He looked into the barrel and somehow hit the trigger. The shot went right through his head. There were long days afterward when Beret just stayed in bed. Then the house burned down. The family just stood there, robbed of everything. Then, too, Beret lay down for eight days and refused to get up. But she had the courage to start again. The winter after those misfortunes she went fishing again in Lofoten. She made good money and with it bought material for a new house, so she and her family could move in before the next winter set in. They built the mill then, too.”

We passed by a waterfall roaring down toward the fjord. This landscape made me shiver; it was alive in the way that Iceland had been alive, filled with names and memories, and

something older than that, the skeletons of the nomads, the skeletons of fish and reptiles from a time when all had been tropical and warm. Now we were climbing; surely it was more than five kilometers that Trouser-Beret had to walk from the fjord to her lakeside home. But then, of course, she'd had her white horse. I pictured her in her colorful blue Sami tunic, with wadmal or skin trousers.

The sun was coming out and the landscape was transformed from harsh to bright. The lake had no firm shore; it was marshy at the edges, tea-dark, almost black in the middle, with white birches all around. I put my hand in my pocket, felt the sharp mineral edges of the rocks I'd picked up.

There were no traces now of their house, rebuilt with such courage after the fire. Dypvann meant “deep water,” and it had been called that in Beret's time as well. Hilgunn remarked conversationally as we drove past, “Her husband took that name after a while. He was Peder Thomassen Dypvann. They were all Dypvann.”

“Beret was Dypvann, too?”

“Yes.”

“So then she had three names. She was Beret Paulsdatter. And Buks-Beret. And Beret Dypvann. Dypvann,” I mused. “What a beautiful name. That's a name I wouldn't mind having. Could I take it, do you think?”

Hilgunn glanced at me a little strangely and rebuked me, as the historian she was, “You can't take the name of a place you don't live.”

We drove a little farther, slowly, peering through the trees. Hilgunn had a zest for life that I envied, and more than that, a vocabulary, a deep remembering. I would like to know the names of all the rocks, all the lakes, all the trees. I would like to

be from a place as fully as she was. Southern California, where I'd grown up, was buried under a million tons of concrete and asphalt. Greenwood in Seattle referred to a thick dark forest that had been cut down a hundred years before I moved there. In America it was hard to be from a place that wasn't constantly changing. Then Hilgunn said, “But you know, Beret had a fourth name; it was her real name that no one knows. I mean, it was her Sami name. People weren't allowed to write down their Sami names on the church registers, so they've been forgotten.”

I didn't say anything to this, but I took it in. The sun struck the black water and the white birches. It didn't matter where I was from; I was here now. I could name myself. I could choose whatever name I wanted, whatever address I needed to call home.

STATUE OF A WOMAN STARING OUT TO SEA

T

HEY CALL

it the Lofoten Wall, this island chain that seems to rise up sheer and black out of the Norwegian Sea, frosted with white in winter, emerald green in summer, jagged-spined as a prehistoric beast. Our ship, the coastal steamer

Lofoten,

had made the crossing from Bodø, a town just above the Arctic Circle on the Norwegian coast. We were now approaching the town of Svolvær at about seven on a cloudy violet evening shot with gold. At the end of a rocky causeway in the harbor, high on a pillar, stood a bronze statue of a woman, waving. Her long skirt blew in the sculptor's breeze; she had a kerchief on her head and a shawl around her shoulders.

I'd seen other statues like this on my voyages north, sometimes at the site of a terrible fishing disaster, where many men lost their lives. There's a mammoth granite figure of a woman at Gloup on the island of Yell in Shetland, recalling a terrible summer storm in 1881 that swept away six fishing boats with fifty-eight men. In the Faroes, at Gjógv, where two boats capsized in the surf in 1870 and seventeen men were lost, a monument portrays a cluster of three, a mother with her two children clinging to her skirts. In Ã

lesund, Norway, a woman shading her eyes and staring seaward perches on the edge of the harbor, while farther north, in Rørvik's town square, looms a bereaved-looking woman with her arms crossed below her chest, and a small boy beside her. Invariably, the statues were called “The Fisherman's Wife” or “Waiting.”

“This is the Fisherman's Wife,” said a new acquaintance, Maggie, who'd joined me on deck with her friend Helen. “I read about it in the guidebook. She's supposed to be waving to the husband who's gone off fishing and might not come back.”

“Oh, that's sad then,” said Helen. “I thought she was waving hello to us!”

Maggie grumbled, “As if a busy woman would have time to stand around waving to some guy in a boat. She was probably milking the cows at home. Where's the statue of the woman milking the cows?”

“Where's the statue of the Viking woman warrior ready to go off pirating and raiding?” I asked.

“I know there were Vikings up here,” said Helen, looking puzzled. “But the women didn't go to sea, did they?”

T

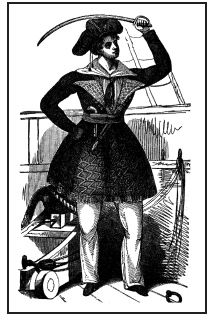

WELVE CENTURIES

ago, long before Grace O'Malley commanded a fleet of pirate galleys that struck fear into the hearts of the Galway merchants and put the English to flight, another woman raider and warrior roved the northern seas in search of loot and a good fight. She was the Viking princess Alfhild, and her deeds, true or not, come down to us through the work of the medieval historian Saxo Grammaticus, whose early-thirteenth-century

History of the Danes

mixes genealogy, saga, and myth. Fascinated with the heroic pagan past, this Christian scholar knew enough to disapprove of the women warriors whose stories he toldâstill, he told them with relish. Some three hundred years later another chronicler, the exiled Swedish bishop Olaus Magnus, was also to write about Alfhild (or Alvild, as he called her) in a chapter entitled “On Piracy by Noble Maidens,” in his comprehensive work,

A Description of the Northern Peoples,

first published in 1555.