The Pirate Queen (45 page)

Authors: Barbara Sjoholm

I had the sense that it wasn't just the kiddies who were a bit bored with stately homes. The Brownes didn't even live in this grand mansion any longer, but down the road. For Jeremy, showing visitors the collections of plate and silver, Waterford glass, paintings, and furniture had paled next to creating his amusement park, tucked discreetly behind trees so little was visible from the windows. Soon we were out of the house, and the next thing I knew I was sitting next to him in the small open car of a miniature train. The engineer pulled the steam whistle and off we chugged. All my life I'd read British novels with lords and ladies in them. In previous centuries they were haughty and proud. In the twentieth century they were sometimes, on the

contrary, depicted as terribly modest, even off-hand, about their aristocratic roots. Still, nothing had quite prepared me for the experience of whizzing round a train track with an ebullient marquess who talked openly of restoring the family fortunes as he created a place that everyone could enjoy.

For several years, he told me, he'd been haunting amusement parks in England and Europe, trying to figure out which rides were most popular. After we stepped out of our train car, he led me over to see several of the ones they'd created here, including his favorite, the log flume. It was a modified roller coaster with a western theme; the cars, shaped like rough brown logs, climbed laboriously up a track and plunged steeply into a pool. There was a lot of shrieking at the plunge and a satisfying amount of water flying around.

“I've been thinking of developing more of a seafaring theme here,” Jeremy said buoyantly as we watched a car containing a trio of eight-year-old girls inch up the steep track. “Now that we have the statue of Grace, we're beginning to build on her connection with Clew Bay and Clare Island, pirates, castles, all that sort of thing. Pirates are very popular these days, don't you think? I'm imagining a sort of flying gondola ride, with the gondolas as pirate ships, you see? Grace O'Malley, Pirate Queen, pirate galleys, swashbuckling and so on. Great fun, don't you think?”

Grace as entertainment for children? The shocked purist in me vied with the child. After all, I'd grown up in a land of amusement parks. The Pike in Long Beach was once famous all along the West Coast for its ballrooms, swimming hall, and daring rides, like the Jackrabbit roller coaster. Seedy as it became throughout the sixties when I knew and loved it, the Pike was a part of memory's vivid landscape, never displaced by the glossier

and more wholesome nature of Disneyland in Anaheim. Lord Altamont and I watched as the log car, with three little girls inside, cranked up to the top of the incline. We fell as silent with anticipation as they had. In the seconds before they began to scream with delight and fear as the car tilted and whooshed down, I remembered that all eight-year-old girls have a pirate inside. The only difference was that a Pippi Longstocking or a Grace O'Malley had never had to give up the dream. Both young Grace and Pippi would have loved a pirate gondola ride, as I would have.

And Jeremy, who had five daughters, laughed with me to see the girls, arms held high, come flying down the slope into the pool, to make a deliriously happy, watery splash of a safe landing.

T

HE NEXT

morning the clouds were ominous, but I decided anyway to go back to Westport House and take another private look at the statue. It was pouring by the time I'd walked through town; dripping and dark, the grounds were quite deserted. The bank holiday was over, and the amusement park would only be open weekends until July. The festive mood of yesterday had turned drear and melancholy. The wind pulled at my coat; rain crept up my pants legs, under my collar. It strangely felt a great deal like my journeys around the North Atlantic several years ago, when I had been soaked and windblown so much of the time, and that gave my walk an odd familiarity.

I placed myself in front of the larger-than-life bronze statue. Rivulets of water ran down her face and neck. The plaque, and the unveiling, would come in several weeks. Right now, Grace stood, not exactly as I'd imagined her, on a plinth of

granite. She was bold certainly and brave and farseeing; she was big, she was tough, she looked every inch a warrior and a mother. Yet, her costume of bodice and skirt didn't seem suitable for seafaring, and she had her back to Clew Bay.

I felt ungrateful. After all, I believed so thoroughly by now in the necessity of memorializing women and their achievements. Finally a statue of a maritime woman! A statue of Grace O'Malley, the Pirate Queen! Yet I stood there feeling vaguely disappointed, only because she wasn't my Grace O'Malley, the Grace I had carried in my head all this time. My Grace would have had shorter hair and a gash on her forehead; she would have worn a doublet and hose, had a spyglass to her eye, and been looking out to sea.

At the symbolic end of my journey,

mo thuras,

rituals still failed me. Once again I took a photograph, many in fact, from every angle, and then I trudged out of the beautifully landscaped, summer-wet grounds, the ancient oaks, and chestnuts soughing in the wind, and back into Westport.

There, on the spur of the moment I called a cab and asked the driver to take me out to Rockfleet, to Carraigahowley Castle. On the way he brought me up to date on Clare Island. The Belgians who'd turned the lighthouse into a bed-and-breakfast had moved on, and the property was again in private hands, owned, the driver said, by a titled lady from England. He knew about Xena's recent visit here, too, and the Discovery Channel program.

We discussed the many changes in Ireland over the last decade and he wondered, as did so many here about Americans, whether I had Irish roots. When I told him about my grandfather, he asked me what I was called.

“Sjoholm,” he said. “What's that for a name?”

“Swedish,” I said.

“But you're Irish? You have relations here, you say?”

“Yes, outside Dunmanway. I had Swedish and Irish grandparents.” I didn't tell him that I'd found the name of Sjoholm, not inherited it. Or that my new name came from sea and island, or that it made a picture in my mind when I said it, of an island sometimes hidden, sometimes visible in the tides. That it felt more nearly mine than my father's adopted name ever had. I certainly didn't tell him that perhaps the Norns had bestowed the name on meâbelatedly, to be sure. No need to sound too mystical.

“It's hard to spell,” I admitted. “But I still like it.”

“Well, now, and wouldn't you, if it's your name?”

“Tis.”

O

NE THING

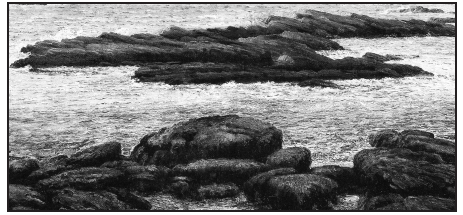

about a castle: It doesn't change in just a few years when it's been standing there for centuries. Grace O'Malley's favorite fortress was just as dankly sea-pungent as I remembered it, the stones around its base just as slippery with kelp and

spume. It had stopped raining, so I'd asked the driver to leave me and come back in an hour, then I walked around the tower and breathed deep of the bladder wrack and rockweed along the shore of the inlet. I had come a long way to do somethingâI wasn't sure whatâto make an end to my pilgrimage around the coasts of the North Atlantic in search of histories and folklore about the legendary women of the sea. It was long ago now that I'd sat on the rocky shores of Cape Cornwall wondering what those stories might be and how to discover them.

Now I knew that many of these stories had been kept alive in old books and family letters, to be rediscovered by relatives and researchers who believed that they were worth passing on. Grace would always be my favorite, but now I knew she wasn't the only maritime woman of the North Atlantic, just one of the most colorful and best remembered. I imagined that in years to come her historical importance would be recognized, and her popularity would continue to rise. Not too far in the future, perhaps, were a theme park and a movie, and perhaps video games and dolls and other merchandise. Pirates, as Jeremy had said, were very popular these days. Whether FreydÃs would ever have a statue, whether Janet Forsyth would have a film about her witchcraft trial were open to conjecture. But I felt that I had proved, to my own satisfaction at least, and in my own idiosyncratic way, that women had a centuries-long history with the North Atlantic. “Women and the sea?” I'd been asked over and over. And now I had something behind me when I answered, “Yes.”

The tide was coming in. For now, there was just me and the castle and Clew Bay. If I half-closed my eyes, I could see Grace O'Malley's favorite galley anchored out in the small bay. I could hear her swearing cheerfully behind me in the top floor of the

castle, spyglass to her eye as she stood watching the clouds blow in from the Atlantic. I gathered a few stones and made a pile, the larger, flatter ones on the bottom, the smaller ones on top, until I'd made a cairn: a signpost, a memorial, a statue of seaweed-spackled stone. I settled back to watch the tide turn the cairn into an island, and then take the stones and submerge them. I took a long, satisfied breath of the salt air and was happy, as I always was, by the sea.

Introduction: Crossing Clew Bay

Since I began researching and traveling, several welcome general books have been published in this field. See Joan Druett's

She Captains: Heroines and Hellions of the Sea

(New York: Simon and Schuster, 2000) and David Cordingly's

Women Sailors and Sailors' Women: An Untold Maritime History

(New York: Random House, 2001). Both these books have chapters on female pirates, as well as other seafaring women around the world.

Chambers, Anne.

Granuaile: The Life and Times of Grace O'Malley

(Dublin: Wolfhound, 1979; revised edition, 1998), I'm deeply indebted to Anne Chambers for her pioneering research on Grace O'Malley. All quotes from English state papers, as well as ballads about Grace come from Chambers's biography. There is a great deal of folklore about Grace O'Malley, and Chambers is careful to distinguish between the legendary aspects of her character and the facts that are known, as other more fanciful writers are not. However, “legendary” doesn't necessarily mean untrue. A rich source in Chambers's research was the folklore collection at the University College of Dublin. In the 1920s and '30s, children all over Ireland were encouraged to interview their relatives about stories from the past. In the case of Grace O'Malley, there were many tales from County Mayo, preserved for four hundred years in folk history, which told of her personal life and great deeds at sea and on land.

Stanley, Jo, ed.

Bold in Her Breeches: Women Pirates Across the Ages

(London: Pandora/HarperCollins, 1995).

Chapter One: Grace O'Malley's Castle

Chambers, Anne.

Granuaile: The Life and Times of Grace O'Malley

(Dublin: Wolfhound, 1979; revised edition, 1998).

Fairburn, Eleanor.

The White Seahorse

(London: Heinemann, 1964). A historical novel about “Graunya O'Malley.”

Leask, Harold G.

Irish Castles and Castellated Houses

(Dundalk, Ireland: Dundalgan, 1999).

Chapter Two: The Pirate Queen

Chambers, Anne.

Granuaile: The Life and Times of Grace O'Malley

(Dublin: Wolfhound, 1979; revised edition, 1998).

Yeoman, Peter.

Pilgrimage in Medieval Scotland

(London: B. T. Batsford Ltd, 1999). For a discussion of

an thuras

(alternative spelling:

an toras)

as a form of pilgrimage.

Chapter Three: At the Edge of the Sea Cauldron

Chambers, Anne.

Granuaile: The Life and Times of Grace O'Malley

(Dublin: Wolfhound, 1979; revised edition, 1998). For the story of Howth Castle.

Grant, Katherine.

Myth, Tradition and Story from Western Argyll

(Oban: Oban Times Press, 1925). For stories about the Cailleach, and the source of details about Corryvreckan as the cauldron in which the Cailleach washes her blankets.

Hull, Eleanor.

Folklore of the British Isles

(London: Methuen, 1928). For the story and related quote about the nine daughters of Ãgir, who grind out the meal of Prince Hamlet.

Mackenzie, Donald.

Scottish Folk-Lore and Folk Life: Studies in Race, Culture and Tradition

(London: Blackie, 1935). For the most comprehensive survey of the Cailleach as “the Scottish Artemis,” and for the suggestion that Muileartach is the Cailleach's ocean form. The verse about Muileartach comes from Mackenzie.

Marwick, Ernest.

The Folklore of Orkney and Shetland

(London: B. T. Batsford, 1975). For the story of the Mither o' the Sea.