The Pirates and the Nightmaker

Read The Pirates and the Nightmaker Online

Authors: James Norcliffe

It’s 1740 …

The

Firefly

is taken in the night by pirates who sail the Caribbean. The ship’s boy and a handful of men are set adrift in a jolly-boat. Without food or water the half-starved men eye up the young boy.

Astonishingly, a mysterious Mr Wicker saves the boy by turning him into an unearthly creature — an invisible flying boy with beautiful emerald-green wings.

When the boy is drawn to a ghost ship sailed by Captain Bass, he learns of the dangerous power of a magical astrolabe which Mr Wicker desperately seeks — and why Wicker must never find it.

The boy cannot trust Wicker … but is there anyone he can trust? Captain Bass? Sophie Blade, the pirate’s daughter? And who can return him to himself?

A strange and mischievous story written with exceptional style, pace and grace — a true classic in the making.

Dedicated to Héctor Guarín and

Julieta Kappaz de Guarín,

who showed us Cartagena de Indias

- Title Page

- Dedication

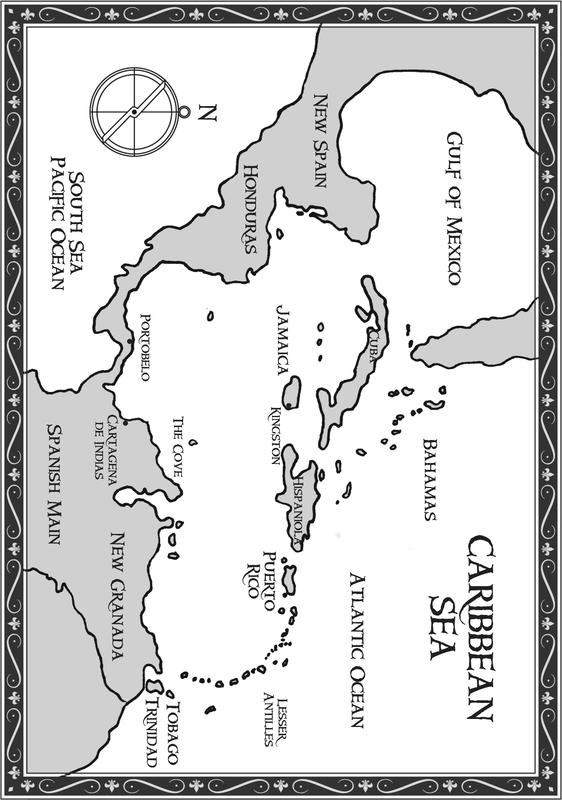

- Map

- PROLOGUE

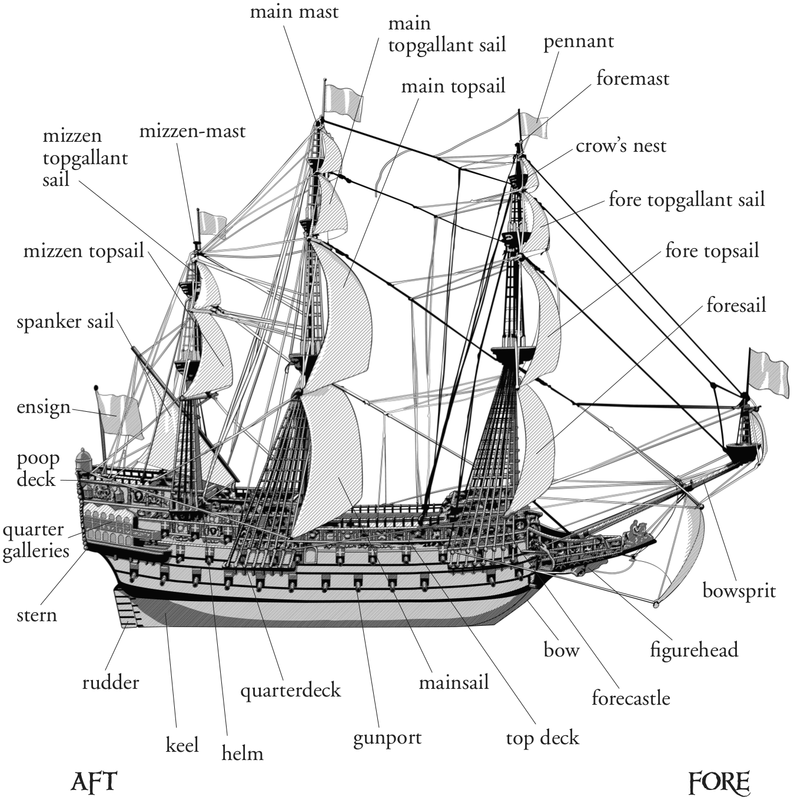

- EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY SAILING SHIP

- CHAPTER 1

H

OT

C

OPPER

S

KY - CHAPTER 2

T

HE

H

ARBOUR

C

LEARED - CHAPTER 3

A

S

G

REEN AS

E

MERALD - CHAPTER 4

A P

AINTED

S

HIP UPON A

P

AINTED

O

CEAN - CHAPTER 5

B

EYOND THE

S

HADOW OF THE

S

HIP - CHAPTER 6

O

NE THAT

H

ATH

B

EEN

S

TUNNED - CHAPTER 7

S

TILL AS A

S

LAVE - CHAPTER 8

T

HE

S

PECTRE

B

ARQUE - CHAPTER 9

T

HE

S

TAR-

D

OGGED

M

OON - CHAPTER 10

S

WEETLY

B

LEW THE

B

REEZE - CHAPTER 11

T

HE

H

ARBOUR

B

AY - CHAPTER 12

HIS

S

KINNY

H

AND - CHAPTER 13

A

ND

W

E

D

ID

S

PEAK - CHAPTER 14

A R

OARING

W

IND - CHAPTER 15

T

ELL

M

E,

T

ELL

M

E - CHAPTER 16

A

H

W

ELL-A-DAY - CHAPTER 17

T

HE

F

AIR

B

REEZE

F

LEW - CHAPTER 18

T

HE

F

URROW

F

OLLOWED

F

REE - CHAPTER 19

V

ELVET

B

LACK - CHAPTER 20

S

WIFTLY,

S

WIFTLY - CHAPTER 21

L

OUD

U

PROAR - CHAPTER 22

F

AREWELL,

F

AREWELL - EPILOGUE

- HISTORICAL NOTE

- GLOSSARY

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- About the Author

- Also by James Norcliffe

- Copyright

It had been a long, dusty walk from Great Ayton already and he had come only about halfway. His bundle was not particularly heavy for he had few possessions to bring with him. He was headed for the village of Staithes on the Yorkshire coast, but he wished that he weren’t. He was a child of the open air and the rolling downs west of the farm. He hated the prospect before him of standing behind a counter in a dark shop measuring out lengths of ribbon for sharp-tongued and impatient housewives.

But that was his future and it had been arranged before he had time to really understand what was happening. Letters had been exchanged between his father and Mr Sanderson, who was by all accounts a kind, god-fearing man. He might just have well been a monster, though, for all the pleasure the boy took in thinking about his life to come.

A cramped shop, a cramped village, a cramped and endless existence, the minutes measured out in thimbles and pins.

He had come upon a stream tumbling over a succession of small dams and the pathway followed it for some way. There was a bend in both path and river and when he turned the

corner he saw a small mill built into the bank and shaded by ancient alder trees. The wheel creaked and splashed as it turned in the stream and the water fell into a deep dark pool below.

The shade was welcome and the boy walked to the side of the pool and shrugged off both bundle and jacket. After supping at handfuls of the clear cold water he lay back in the sweet grass to rest. He contemplated a mouthful or two of the bread and cheese his mother had wrapped for his journey but decided to preserve it for a time when his need was greater.

He heard footsteps and looked up to see the miller, patting at his dusty smock.

They shared a few words pleasantly and the boy asked whether he was on the right road to Staithes and how far he had to go.

The miller tugged at his beard, offered directions and suggested a distance and time, which was more or less what the boy suspected.

When the miller added that he could be hard-pressed to complete the journey before nightfall, the boy thanked him and stood up. He pulled his jacket back on, gathered his bundle and picked up his walking staff.

He said farewell to the miller and although he would have preferred to have rested for a longer time in the softness of the butter-sweet grass, he set off on his journey again.

Soon he had left the stream and the trees behind him and was walking between hedgerows of hawthorn still in flower even though spring was all but over.

When he turned a bend at the top of a small rise, however, he stopped in astonishment.

Had he not been frozen by the sight before him he would have turned on his heel and fled.

As it was, he dropped his staff with a clatter and his bundle fell from his shoulder.

Sitting on a stump to one side of the path was a strange creature, the strangest creature the boy had ever seen.

He was wearing filmy garments of green that fell like birch bark down his arms and legs.

But strangest of all were the great green wings that were folded on either side of his shoulders, beautiful wings with iridescent green feathers that gleamed and shivered as their filaments caught the sun.

Their beauty was so startling the boy almost forgot his fear, the initial horror that he may have stepped in front of the devil himself, and wondered instead whether he had been visited by an angel. With this thought he raised his hands in awe, knowing that angels could be bringers, no less than devils, of dreadful things. A burst of sufficient courage came to him, enough so that he could turn and flee back down the path, and he was about to do so when the creature spoke in a clear, ringing voice.

‘Stay!’ he cried. ‘Stay! You must stay!’

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY

SAILING SHIP

I had never been so afraid in all my life.

As a loblolly boy on a ship of the line you get to see fearful things, things no boy should ever see: frightened men, men with the fear of death in their eyes, and, often enough, death itself in their eyes. But this was different. I’m the one who was frightened now and with very good cause.

I looked around at the men in the jolly-boat. It was hot. The sun was high in the sky and beat down like a belaying pin. It had been several days now and although the water had been rationed it was almost at an end. The biscuit, our only food, had ended already.

Most of the men, six, seven or so, were frightened too. I could almost smell their fear; their fear of dying of the heat or dying of thirst and hunger.

These were the things that frightened me as well, but there was much more. It’s what I was seeing in the men’s wild eyes as, every now and again, they glanced at me. It was as though they were considering the wares in a butcher’s cart. At such times I saw them instinctively touch the hasps of their daggers before they would catch my eye and look away.

Not all of them.

Back in the stern of the boat far away from me lolled Captain Lightower and the ship’s surgeon, Dr Hatch, whose servant I was. My master had comforted himself with rum — which he had not been prepared to share — and was only at that point emerging from a three-day stupor of groaning and snatches of singing.

The captain, on the other hand, had hardly said a word since the ship was taken. He had just lain there, glowering about at the easy rolling sea and growling every now and again. Despite his anger, whenever we glanced at each other, I did not see rage or hunger in his eyes, I saw bitterness.

In the prow of the boat, just behind me, the passenger sat. He was a strange figure, a friend of the captain I understood. He was a gentleman, I’ll warrant, certainly no sailor. On our passage out he wore the clothes of a man with a purse of gold: leather shoes with silver buckles, and a black greatcoat to guard against the wind. Now he sat by himself in the prow stripped to trousers, a silk shirt and a tricorn hat to protect his head from the beating sun. Like the captain he was largely silent, but I imagine for different reasons because he seemed neither angry nor desperate. If I had to describe the way he was treating our predicament, I’d say it was mocking. This was very strange to me, for our situation was dire. Certainly he seemed to show no fear. In a way, this attitude scared me as much as the men’s growing agitation and I was glad the passenger was at my back.

We had been bound for Jamaica to join our flotilla when we were boarded. The attack was swift and totally unexpected.

It was deepest night and for some unfathomable reason — perhaps rum, perhaps treachery — neither those at the helm nor those on watch were aware of the assault until it was too late. Possibly it was treachery. The attack had been so efficiently carried out that no lives I’m sure had been lost. It was odd therefore that only such a handful of our crew had been ordered into the jolly-boat and cast out onto the ocean.

It must have been pirates, although pirates of a strange stripe. Most pirates would have cut us to pieces as a bloody gift for their kinsfolk, the sharks, although now I was no longer so sure that casting us adrift in a jolly-boat — what a fantastical term for the boat we were on! — was any act of human kindness.

It could not have been the Spaniards. Had it been the Spaniards, the ones they spared would have been bound in irons and taken to some island or mainland stronghold and held to ransom perhaps with their ears cut off, like poor Captain Jenkins.

It was a mystery, but now in this heat, this thirst, this hunger, I no longer cared to puzzle at it.

This sea I knew was peppered with islands and it was my urgent prayer that we would find one before the heat, thirst and hunger drove the men to the deed I knew was in their hearts. However, the sea was as boundless and empty as the sky. I shrank into myself, as if to render me smaller, less noticeable. Foolish, I know, but my terror was ever growing.

Just then, I heard a sardonic whisper at my back.

‘Look at them, Loblolly Boy. They’re measuring you up.’

I glanced quickly over my shoulder. The passenger was staring beyond me at the men. His eyes, dark in the shade of his hat, glittered.

I followed his gaze. What he had meant was all too plain and it was all too plain that he was right.

Despite the heat, I trembled.

‘They’re sharing you out. I’ll wager that one wants a leg …’

‘Stop it!’

‘Whether I stop it or not, little Loblolly Boy, will not make any difference …’

Why was he doing this? Taunting me? The hunger in the men’s eyes was growing and I could tell it might not be too long before one or more of them made a move. Who could I appeal to? The man at my back seemed almost amused at my plight. My master Dr Hatch had no love for me, only love for his bottle. Captain Lightower seemed gripped by his own private demons.

I glanced over the gunwale. Would it be better to slip into the water? Would it be better to let my drowning deny what was in their wicked hearts?

The sea was calm, beguiling. It slapped against the boat slyly, nudging it back and forth. Apart from this slip slap the silence was complete and almost unbearable.

Then, suddenly, the captain broke the silence by barking in the direction of the passenger. ‘Well, Mr Wicker, see what a catastrophe your devilry has led to?’

The passenger was unmoved by the captain’s passion. Instead he turned to him and smilingly said, ‘My devilry,

Captain? You’re not suggesting I’m the one responsible for your present predicament, are you?’

‘Don’t fob me off with your humbug, man!’ cried the captain.

‘Or blaming me for the appalling stewardship of your vessel?’ responded the passenger easily.

This exchange surprised me, especially the captain’s bitterness. I did not understand it, nor did I understand the passenger’s carefree reply. I had thought that the man the captain called Mr Wicker was a friend of his; now it appeared as if they were enemies. It was not unusual for a gentleman acquaintance of the captain to voyage with a navy vessel, particularly if the said gentleman was

well-connected

or perhaps a man of science, as I presumed this Mr Wicker was.

It now looked as though Mr Wicker had found means other than friendship to secure his place on board and that the captain had not been happy about it. However, what Captain Lightower meant by devilry, I had no idea at all. I had scarcely seen the gentleman on our way out; since leaving Portsmouth he had remained in his cabin for most of this time, I presumed for the reasons most unseasoned voyagers stay in their cabins.

The captain did not respond to the passenger’s charge. He merely grunted scornfully and slumped back into himself. This interruption to the silence, however, had enlivened the men a little and one or two muttered to each other. The muttering did not bode well for me and I found myself shrinking again even further and instinctively moving closer

to the stranger. I imagine that this was because, despite his goading, I felt that he did have an authority and

self-possession

above all of the other wretches on board.

I sensed that if anybody on the little boat could save me it would be him, although how he could do this was beyond my understanding.

Suddenly the boat was set a-rocking by one of the men standing up. It was Jacob Stone, the bosun’s mate. He was not generally liked, being a lickspittle and a bully, toadying to his superiors and lording it over those he considered beneath him. I generally avoided him as his usual pleasure was to cuff my ears, aim a kick at me, or tell me I was damned. As there was no mast, he had to balance himself by standing legs apart, forcing the boat to seesaw violently. His purpose was to gain height in order to scan the horizon all about us, hoping for some indication of land. There was clearly none.

‘Sit down, man!’ ordered the captain angrily, ‘or you’ll have us all in the drink!’

Stone obeyed at once, causing as much rocking and pitching as he had in climbing to his feet. Once seated again, and as the boat slowly gained its balance on the water, he set about whispering to his fellows and, as they whispered among themselves, once more I felt their lip-licking glances in my direction.

‘I do believe they’re getting hungrier, Loblolly Boy,’ murmured the stranger.

I did not reply. What was there to say? It was such a self-evident fact.

‘Clearly Master Stone has found no sign of rescue on the horizon,’ the stranger added. ‘No comfort there for him, and so I dare say even less comfort for you, wouldn’t you agree?’

‘Don’t do this,’ I whispered.

‘What am I doing,’ said the stranger, ‘except stating the obvious? The sun is hot, the sea is calm, there is no land or ship in sight, the men are parched and getting hungrier, and you are the best thing on board to satisfy that hunger …’

I felt faint with fear.

And then, mysteriously and most unexpectedly, given his ever mocking cruelty, the stranger whispered, ‘Loblolly Boy, if you can move as gently as possible and without rocking the boat as roughly as that fool Stone, then you would be able to sit right up in the bow and I shall sit between you and these who would butcher you for dinner.’

I looked up at him speechless.

Why was he doing this? He did give the appearance of fearing nothing, not even the captain, but he was still only one man, and as far as I knew, unarmed. He could possibly delay their murderous designs, but he could not prevent them. They would have their knives, their daggers, and they were growing ever more desperate. I could not see my master Doctor Drunken Hatch coming to his aid. The men would probably seek the doctor’s surgical skills to cut me up and he would clumsily oblige them. Captain Lightower had already revealed his contempt for the stranger. I did the arithmetic: nine against two. It was not comforting.

All the same, I gave the stranger a small surprised grimace and my muttered thanks.

Immediately, I began to wriggle past him as inconspicuously as possible and without rocking the boat too much.

Of course, both were impossible. How could I be inconspicuous when I was the constant focus of the desperately hungry men? And how could I move even a finger or a toe on that small jolly-boat lolling on a rolling sea without setting it lurching?

‘Keep yourself still, dammit!’ barked the captain, glaring in my direction, but thankfully he did not order me to return to my place. One or two of the men half-rose, as if to prevent me from shifting, but then quickly sat down as the boat began to rock even more violently.

‘That wasn’t difficult, was it?’ murmured the stranger, turning to me.

Now that the bulk of his body shielded me at least from the gaze of the others, I felt slightly more secure, although I knew in my heart that this was an illusion. Sooner or later, the men would come for me, and the stranger’s body would then be no more defence than a calico curtain in a window.

I suspected that the time would be dusk or even darkness. Whatever they were, whatever their desperation, the men were still human, and would prefer not to see their inhuman depravity revealed in the full glare of sunlight. No, it would be when there were shadows and darkness, when the boat bobbed in a black sea, and there would be little more than starlight to catch the glint of their knives.

My strange protector may have understood this as well, for after some time he whispered to me, ‘It occurs to me, little Loblolly Boy, that we do not have much time; that

we should make our move before the sun sets, for in these tropic climes the sun sets with surprising expedition. We must take these scoundrels by surprise.’

Make our move? Take them by surprise? Was he suggesting that the two of us, one man and a mere stripling, should attack the lot of them, our only weapon being surprise?

To me, that seemed a somewhat inadequate weapon.

‘What do you mean?’ I whispered.

‘Trust me,’ he murmured. ‘I have certain abilities, you might say, that will utterly confound these wretches. I am rather weary of this becalmed little boat, and even wearier of its company. I think it’s time to say farewell to both.’

I began to think that the stranger was mad, that the sun had affected his reason. He was speaking of leaving the boat and its company. He was talking as if he were back in Portsmouth Town, not adrift in the vast emptiness of a tropical sea. I gave him what I hoped was an encouraging look, but I was sore afraid he’d lost his mind.

Or was he considering giving ourselves to the sea?

Despite the dark fears plaguing me there remained some small security in having Mr Wicker between me and the others. Perhaps because of his mocking recklessness, I sensed strength. I eased back into the prow and glanced around the ocean. While it promised nothing at least it did not stare at me with naked hunger. All at once, not far astern, I saw a flash of silver, and then another, and then to my astonishment there was a great scattering of silver rising in graceful arcs and falling back into the water only to rise and fall and rise and fall again.

Mr Wicker had turned back to me and now followed my gaze.

‘Flying fish,’ he murmured.

‘They’re beautiful,’ I whispered, ‘such joy.’

‘Perhaps,’ Mr Wicker said, ‘but I suspect it is more likely to be terror.’

‘Terror?’

‘I imagine that they’re leaping out of the water because some shark or barracuda is snapping at their tails. Luckily, providence has given them the ability to fly.’

Now, as I looked at the flying fish it did look as if there was something desperate and frantic in their succession of leaps and falls. My wonder at their freedom turned to a slight shudder at their predicament.

‘Alas, little Loblolly Boy,’ murmured the stranger, ‘would that providence had given you the ability to fly.’

He was teasing me again.

‘Would that not be a blessing, for there are sharks gathering about you, too.’

I willed him to turn away, and that failing, I turned away myself, muttering once more, ‘Don’t do this to me.’