The Plantagenets: The Kings That Made Britain (20 page)

Read The Plantagenets: The Kings That Made Britain Online

Authors: Derek Wilson

Tags: #HISTORY / Europe / Great Britain, #Fiction

Lollardy continued to be a problem, and in 1407, during a church council meeting in Oxford, Archbishop Arundel set forth certain ‘constitutions’ to strengthen the hand of the authorities in dealing with heresy. One read: ‘We … resolve and ordain that no one henceforth on his own authority translate any text of Holy Scripture into the English or any other language by way of a book, pamphlet or tract and that no book, pamphlet or tract of this kind … be read in part or in whole, publicly or privately, under pain of the great excommunication.’

3

No such draconian regulation operated in any other European country. Prince Henry tried to undermine the archbishop by challenging his authority in Oxford, but the king, continuing his policy of strong support for the church, backed Arundel.

Relations between father and son were basically cordial, but tensions inevitably developed. The prince gradually assumed more control of policy but the king was anxious not to be sidelined. In 1411 they fell out over policy towards France. The prince wanted to provide the Duke of Burgundy with military help in his contest with the Orleanists. The king originally backed this plan but subsequently changed his mind. As a compromise a small force led by the Earl of Arundel went over to France in September. The prince was eager to install his own confidants in the major offices of state, and early in 1410 Sir Thomas Beaufort became chancellor and Lord Scrope of Masham was appointed treasurer. However, at the end of the year Henry IV dismissed both men.

The king now began to show a preference for his second son, Thomas (created Duke of Clarence in 1412). Prince Henry ceased to preside over the council, and when an army was sent to France Thomas, not Henry, was its leader. This time the king’s forces were committed to the Orleanist camp. Both sides in the French civil war had competed for English support, and the Orleanists had made the better offer. They guaranteed Henry’s rule of Aquitaine and promised to augment it with other adjacent territories. In the event, Henry went to a great deal of expense for nothing. By the time his army reached the theatre of war, the contending parties had reached an agreement that took no account of English claims and ambitions. Prince Henry brought several armed retainers to London and made angry protests about his treatment, but he was eventually reconciled to his father who, by the end of the year, was again seriously ill. Henry IV died on 20 March 1413.

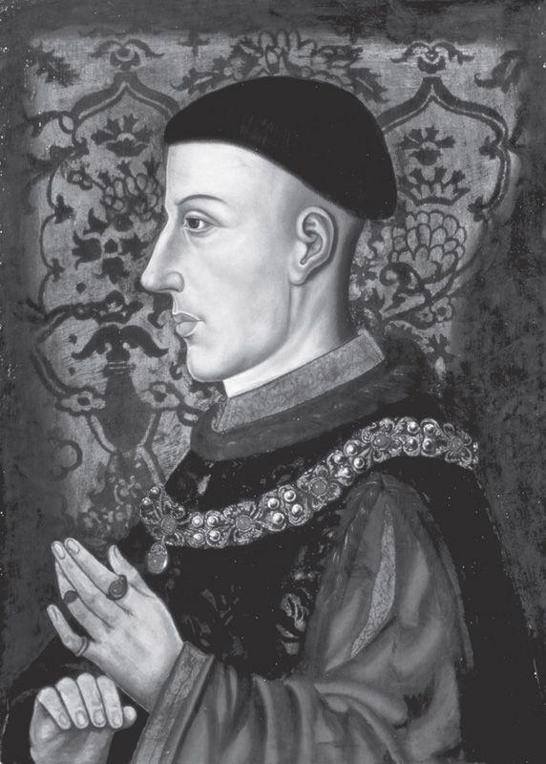

HENRY V 1413–22

Henry V’s brief reign lasted for nine years and five months, and the king spent half of that time in France. He was England’s most successful warrior-king since Henry II, and, like his namesake, he was constantly on the move. His military exploits were famously dramatized by Shakespeare, but they were scarcely less ‘heroic’ in reality. He made good the English claim to the throne of France and had he lived to cement his military and diplomatic achievements might have linked the crowns permanently.

1413–14

Holinshed’s Chronicle

describes Henry as having had a misspent youth and having been a frequenter of bad company but insists that, on his accession, he turned over a new leaf. If he did indulge in a dissolute life during his father’s last years it is likely to have been out of frustration with a king who was incapable of wise and measured rule. The prince was impatient to reform the government, and its whole mood changed as soon as he came to power.

Henry V’s first objective was to heal the breaches that had caused so much disruption during his father’s reign. He had the advantage that Wales and Scotland now posed no serious threat to the peace of the realm. Glyn Dwr’s freedom movement had run into the sand, and the continued detention

of James I of Scotland proved effective in keeping the northern border quiet. Henry could concentrate on reconciling those of his own people who still regarded the ‘Lancastrians’ (Henry IV and his son) as usurpers. In December 1413 he had the body of Richard II disinterred from its obscure grave at Kings Langley and placed in the impressive tomb that the late king had had prepared for himself in Westminster Abbey. This served the double purpose of demonstrating Henry’s respect for Richard’s memory and of emphasizing that Richard was definitely dead, for there were still some ‘Yorkist’ partisans who clung to the belief – or hope – that the old king was hiding in Scotland or some other sanctuary and waiting to reclaim his throne. The king offered pardons – at a price – to those who had been implicated in the recent rebellion, and he began negotiations for the release of Henry Percy, Hotspur’s son, who was being held in Scotland. It was necessary to rehabilitate the Percys because they were the only family who could ensure the loyalty of the north.

But Henry’s first problem came from nearer home. Sir John Oldcastle, Baron Cobham, was a seasoned warrior who had fought in Wales and France and was personally known to the king. He was a substantial landowner in Herefordshire and Kent, and he was also a convinced Lollard, one of a small group of shire knights who formed a sort of ‘aristocracy’ in the largely working-class world of English heresy. Archbishop Arundel and his agents were still enthusiastic about tracking down suspected Lollards, and in the early days of the reign they discovered a cache of heretical tracts belonging to

Oldcastle. Arundel, cautious about proceeding against one of the king’s associates, informed Henry, who ordered a ‘cooling-off period’ while he personally tried to reason with the unorthodox knight. Oldcastle refused to budge from his criticism of the papacy and Catholic doctrine, and after several months Henry gave Arundel permission to instigate proceedings in his own court. Oldcastle was lodged, reasonably comfortably, in the Tower of London.

On 23 September the prisoner was taken to St Paul’s Cathedral for his trial. The case had provoked enormous interest, and the church was packed with spectators, among whom were several men and women who shared Oldcastle’s beliefs. The knight was duly found guilty and handed over to the secular arm. Once again, Henry intervened to allow the prisoner more time for reflection. Plans had probably already been made to rescue him, and on the night of 19 October Oldcastle escaped from the Tower (perhaps with the connivance of sympathetic guards). He was hidden by his friends in the city, and there he hatched a rash plot to seize London while a band, posing as mummers, would go to Eltham Palace, where the court was staying, and take the king prisoner. What the rebels intended to do if their plan succeeded is not clear; perhaps they had not thought that far ahead. Certainly, like the peasants who had risen a generation before, they underestimated the difficulty of taking control of London. On the other hand, their confidence suggests that Lollardy was strong in the capital and that Arundel was right to fear it, though what was afoot was not as extreme as some contemporary chronicles reported.

Oldcastle’s agents travelled the country in the closing days of 1413, whipping up support. Recruitment was well organized, and it appears that various lures were employed to attract supporters – a brewer from Dunstable, for example, appeared wearing gold spurs and with gilded trappings for his horse because he had been promised the governorship of Hertfordshire and was determined to present himself in a style befitting his new station. On the night of 9–10 January several hundred Lollards converged on St Giles’s Fields, northwest of the city beyond Temple Bar. There Oldcastle was to meet them with a band of well-armed retainers. However, too many people were in the conspiracy for it to remain secret, and too few to carry it off successfully. The plot was betrayed, and the king’s men were already in waiting as the groups of conspirators began to arrive. Most of the rebels fled and escaped in the darkness, but 36 were subsequently hanged, ‘upon new gallows made for them upon the highway fast beside the same field where they thought to have assembled together’. Seven of their number were also burned.

1

Oldcastle was among those who escaped, and he managed to remain at large until November 1417, when he was captured in Wales and executed as a traitor.

Henry V’s overmastering passion was making good his claims in France. The existing truce was set to expire on 1 May 1415, and the king hoped to put a permanent end to the long-running war. But he was also determined to have peace on his own terms. In the spring of 1414 he sent ambassadors to Charles VI to present his case. He required recognition as heir to the French crown or, at least, the complete

restitution of all those lands in the southwest traditionally claimed by his predecessors. To cement friendship between the two nations he proposed his own marriage to Charles’s youngest daughter, Catherine. And he asked for a huge dowry. Such extravagant demands doubtless were made as the opening gambit in diplomatic bargaining, but Henry had already decided that he would need to back it up with force. He borrowed large sums of money from the bishops and London merchants, including the wealthy mercer Richard Whittington. Yet as late as December 1414 parliament was urging him to reach an accord with Charles VI by peaceful means.

1415–16

As Anglo-French talks continued, the two sides grew further apart. In March 1415 the dauphin, having reached an agreement with the Duke of Burgundy not to support Henry’s claims, sent a defiant message. Its insolence may have become exaggerated in the telling and retelling, but according to some sources the king of England was sent a case of tennis balls because playing games was more suited to his youth and inexperience than waging war. What may have stung Henry even more than such a rebuff was the charge that he should not lay claim to the crown of France when he was not even the rightful king of England.

While Henry gathered his army and prepared to cross the Channel there were still signs of disaffection at home. Sir John Oldcastle was still at large in the West Country, where

he enjoyed not inconsiderable support, and in March 1415 his London associates fixed notices to church doors in the city warning that their revenge for the St Giles’s Fields fiasco was imminent. There was some overlap with a Yorkist plot that blew up in the summer of 1415. Richard, Earl of Cambridge, and Sir Thomas Grey devised a plan to reunite all those parties that had been involved in the dynastic challenges of Henry IV’s reign. While the king was out of the country they would negotiate Henry Percy’s return to England, reactivate the old anti-Lancastrian alliance, stage a military coup and place the Earl of March on the throne. The conspirators were joined, somewhat surprisingly, by Henry, Lord Scrope of Masham, who had served Henry IV as treasurer, taken part in diplomatic missions for Henry V and was engaged to cross to France with the royal army. It is doubtful that the rebellion could have raised sufficient support to succeed even if (as some suspected) it was backed by French money, but it never got off the ground because the Earl of March revealed the details to the king on 31 July in Southampton, where the army was assembling. Cambridge, Grey and Scrope were swiftly tried and executed.

On 14 August Henry landed on the French coast near the town of Harfleur, on the north side of the Seine estuary, with some 10,500 troops. His immediate plan was to gain control of the river as a preliminary to capturing Rouen and invading Normandy. This would give him access to Paris and enable him to threaten the capital. Having unloaded all his men and equipment, the king laid siege to Harfleur on 17 August. But the town was well provisioned and Henry did not gain

the quick initial victory he had hoped for. Moreover, the marsh estuary was a breeding ground for fever-bearing insects, and English numbers were rapidly diminished by disease, as the

Chronicle of the Grey Friars

recorded: ‘there died many of his people, as the Earl of Surrey, the Bishop of Norwich, Sir John Philpot, and many other knights and squires, and a great many of the common people.’

2

Harfleur did not fall until 22 September.

With time lost and his army much diminished, Henry abandoned the planned ravaging of Normandy and, having sent home the sick and wounded, set out for Calais, where he could rest and provision his men and take stock of the situation. Including recent reinforcements, his army now numbered between 6,500 and 7,000 men. The French had assembled their own army and moved to intercept the invaders. With difficulty Henry got his men across the Somme. Many of them were weak with hunger, fever and long marching, and they did not relish the prospect of the pitched battle that now became inevitable.

On 25 October, the feast-day of Saints Crispin and Crisp-inian, Henry’s small force of Englishmen faced 36,000 of the best knights and foot soldiers in France. The first three hours of daylight saw no action at all, for despite their overwhelming numerical superiority, the French were in no hurry to begin the engagement. They were blocking the road to Calais and were content to let the enemy try to break through. For his part, Henry knew that his only hope of success was fighting a defensive battle on a site of his own choosing. He positioned his main array in a broad defile

between woodland close to the villages of Tramecourt and Agincourt, with archers on the flanks and in the front rank to fire into the expected charge of mounted knights as they were forced by the terrain to shorten their lines. The French chronicler Enguerrand de Monstrelet provides a vivid account of the battle. The English, he explained: