The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business (6 page)

Read The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business Online

Authors: Charles Duhigg

Tags: #Psychology, #Organizational Behavior, #General, #Self-Help, #Social Psychology, #Personal Growth, #Business & Economics

Eugene was seated at a table, given a pair of objects, and asked to choose one. Next, he was told to turn over his choice to see if there was a “correct” sticker underneath. This is a common way to measure memory. Since there are only sixteen objects, and they are always presented in the same eight pairings, most people can memorize which item is “correct” after a few rounds. Monkeys can memorize all the “correct” items after eight to ten days.

Eugene couldn’t remember any of the “correct” items, no matter how many times he did the test. He repeated the experiment twice a week for months, looking at forty pairings each day.

“Do you know why you are here today?” a researcher asked at the beginning of one session a few weeks into the experiment.

“I don’t think so,” Eugene said.

“I’m going to show you some objects. Do you know why?”

“Am I supposed to describe them to you, or tell you what they are used for?” Eugene couldn’t recollect the previous sessions at all.

But as the weeks passed, Eugene’s performance improved. After twenty-eight days of training, Eugene was choosing the “correct” object 85 percent of the time. At thirty-six days, he was right 95 percent of the time. After one test, Eugene looked at the researcher, bewildered by his success.

“How am I doing this?” he asked her.

“Tell me what is going on in your head,” the researcher said. “Do you say to yourself, ‘I remember seeing that one’?”

“No,” Eugene said. “It’s here somehow or another”—he pointed to his head—“and the hand goes for it.”

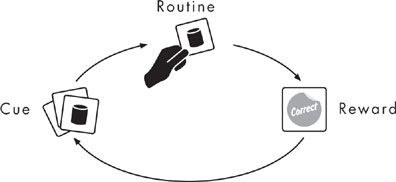

To Squire, however, it made perfect sense. Eugene was exposed

to a cue: a pair of objects always presented in the same combination. There was a routine: He would choose one object and look to see if there was a sticker underneath, even if he had no idea why he felt compelled to turn the cardboard over. Then there was a reward: the satisfaction he received after finding a sticker proclaiming “correct.” Eventually, a habit loop emerged.

EUGENE’S HABIT LOOP

To make sure this pattern was, in fact, a habit, Squire conducted one more experiment. He took all sixteen items and put them in front of Eugene at the same time. He asked him to put all the “correct” objects into one pile.

Eugene had no idea where to begin. “Gosh sakes, how to remember this?” he asked. He reached for one object and started to turn it over. The experimenter stopped him. No, she explained. The task was to put the items in

piles

. Why was he trying to turn them over?

“That’s just a habit, I think,” he said.

He couldn’t do it. The objects, when presented outside of the context of the habit loop, made no sense to him.

Here was the proof Squire was looking for. The experiments demonstrated that Eugene had the ability to form new habits, even when they involved tasks or objects he couldn’t remember for more than a few seconds. This explained how Eugene managed to go for a walk every morning. The cues—certain trees on corners or the placement of particular mailboxes—were consistent every time he

went outside, so though he couldn’t recognize his house, his habits always guided him back to his front door. It also explained why Eugene would eat breakfast three or four times a day, even if he wasn’t hungry. As long as the right cues were present—such as his radio or the morning light through his windows—he automatically followed the script dictated by his basal ganglia.

What’s more, there were dozens of other habits in Eugene’s life that no one noticed until they started looking for them. Eugene’s daughter, for instance, would often stop by his house to say hello. She would talk to her father in the living room for a bit, then go into the kitchen to visit with her mother, and then leave, waving good-bye on her way out the door. Eugene, who had forgotten their earlier conversation by the time she left, would get angry—why was she leaving without chatting?—and then forget why he was upset. But the emotional habit had already started, and so his anger would persist, red hot and beyond his understanding, until it burned itself out.

“Sometimes he would bang the table or curse, and if you asked him why, he’d say ‘I don’t know, but I’m mad!’ ” Beverly told me. He would kick his chair, or snap at whoever came into the room. Then, a few minutes later, he would smile and talk about the weather. “It was like, once it started, he had to finish the frustration,” she said.

Squire’s new experiment also showed something else: that habits are surprisingly delicate. If Eugene’s cues changed the slightest bit, his habits fell apart. The few times he walked around the block, for instance, and something was different—the city was doing street repairs or a windstorm had blown branches all over the sidewalk—Eugene would get lost, no matter how close he was to home, until a kind neighbor showed him the way to his door. If his daughter stopped to chat with him for ten seconds before she walked out, his anger habit never emerged.

Squire’s experiments with Eugene revolutionized the scientific community’s understanding of how the brain works by proving, once and for all, that it’s possible to learn and make unconscious

choices without remembering anything about the lesson or decision making.

1.22

Eugene showed that habits, as much as memory and reason, are at the root of how we behave. We might not remember the experiences that create our habits, but once they are lodged within our brains they influence how we act—often without our realization.

Since Squire’s first paper on Eugene’s habits was published, the science of habit formation has exploded into a major field of study. Researchers at Duke, Harvard, UCLA, Yale, USC, Princeton, the University of Pennsylvania, and at schools in the United Kingdom, Germany, and the Netherlands, as well as corporate scientists working for Procter & Gamble, Microsoft, Google, and hundreds of other companies are focused on understanding the neurology and psychology of habits, their strengths and weaknesses, and why they emerge and how they can be changed.

Researchers have learned that cues can be almost anything, from a visual trigger such as a candy bar or a television commercial to a certain place, a time of day, an emotion, a sequence of thoughts, or the company of particular people. Routines can be incredibly complex or fantastically simple (some habits, such as those related to emotions, are measured in milliseconds). Rewards can range from food or drugs that cause physical sensations, to emotional payoffs, such as the feelings of pride that accompany praise or self-congratulation.

And in almost every experiment, researchers have seen echoes of Squire’s discoveries with Eugene: Habits are powerful, but delicate. They can emerge outside our consciousness, or can be deliberately designed. They often occur without our permission, but can be reshaped by fiddling with their parts. They shape our lives far more than we realize—they are so strong, in fact, that they cause our brains to cling to them at the exclusion of all else, including common sense.

In one set of experiments, for example, researchers affiliated with the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism trained mice to press levers in response to certain cues until the behavior became a habit. The mice were always rewarded with food. Then, the scientists poisoned the food so that it made the animals violently ill, or electrified the floor, so that when the mice walked toward their reward they received a shock. The mice knew the food and cage were dangerous—when they were offered the poisoned pellets in a bowl or saw the electrified floor panels, they stayed away. When they saw their old cues, however, they unthinkingly pressed the lever and ate the food, or they walked across the floor, even as they vomited or jumped from the electricity.

The habit was so ingrained the mice couldn’t stop themselves.

1.23

It’s not hard to find an analog in the human world. Consider fast food, for instance. It makes sense—when the kids are starving and you’re driving home after a long day—to stop, just this once, at McDonald’s or Burger King. The meals are inexpensive. It tastes so good. After all, one dose of processed meat, salty fries, and sugary soda poses a relatively small health risk, right? It’s not like you do it all the time.

But habits emerge without our permission. Studies indicate that families usually don’t

intend

to eat fast food on a regular basis. What happens is that a once a month pattern slowly becomes once a week, and then twice a week—as the cues and rewards create a habit—until the kids are consuming an unhealthy amount of hamburgers and fries.

When researchers at the University of North Texas and Yale tried to understand why families gradually increased their fast food consumption, they found a series of cues and rewards that most customers never knew were influencing their behaviors.

1.24

They discovered the habit loop.

Every McDonald’s, for instance, looks the same—the company deliberately tries to standardize stores’ architecture and what employees say to customers, so everything is a consistent cue to trigger

eating routines. The foods at some chains are specifically engineered to deliver immediate rewards—the fries, for instance, are designed to begin disintegrating the moment they hit your tongue, in order to deliver a hit of salt and grease as fast as possible, causing your pleasure centers to light up and your brain to lock in the pattern.

All the better for tightening the habit loop.

1.25

However, even these habits are delicate. When a fast food restaurant closes down, the families that previously ate there will often start having dinner at home, rather than seek out an alternative location. Even small shifts can end the pattern. But since we often don’t recognize these habit loops as they grow, we are blind to our ability to control them. By learning to observe the cues and rewards, though, we can change the routines.

By 2000, seven years after Eugene’s illness, his life had achieved a kind of equilibrium. He went for a walk every morning. He ate what he wanted, sometimes five or six times a day. His wife knew that as long as the television was tuned to the History Channel, Eugene would settle into his plush chair and watch it regardless of whether it was airing reruns or new programs. He couldn’t tell the difference.

As he got older, however, Eugene’s habits started impacting his life in negative ways. He was sedentary, sometimes watching television for hours at a time because he never grew bored with the shows. His physicians became worried about his heart. The doctors told Beverly to keep him on a strict diet of healthy foods. She tried, but it was difficult to influence how frequently he ate or what he consumed. He never recalled her admonitions. Even if the refrigerator was stocked with fruits and vegetables, Eugene would root around until he found the bacon and eggs. That was his routine. And as Eugene aged and his bones became more brittle, the doctors said he

needed to be more careful walking around. In his mind, however, Eugene was twenty years younger. He never remembered to step carefully.

“All my life I was fascinated by memory,” Squire told me. “Then I met E.P., and saw how rich life can be even if you can’t remember it. The brain has this amazing ability to find happiness even when the memories of it are gone.

“It’s hard to turn that off, though, which ultimately worked against him.”

Beverly tried to use her understanding of habits to help Eugene avoid problems as he aged. She discovered that she could short-circuit some of his worst patterns by inserting new cues. If she didn’t keep bacon in the fridge, Eugene wouldn’t eat multiple, unhealthy breakfasts. When she put a salad next to his chair, he would sometimes pick at it, and as the meal became a habit, he stopped searching the kitchen for treats. His diet gradually improved.

Despite these efforts, however, Eugene’s health still declined. One spring day, Eugene was watching television when he suddenly shouted. Beverly ran in and saw him clutching his chest. She called an ambulance. At the hospital, they diagnosed a minor heart attack. By then the pain had passed and Eugene was fighting to get off his gurney. That night, he kept pulling off the monitors attached to his chest so he could roll over and sleep. Alarms would blare and nurses would rush in. They tried to get him to quit fiddling with the sensors by taping the leads in place and telling him they would use restraints if he continued fussing. Nothing worked. He forgot the threats as soon as they were issued.