The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business (9 page)

Read The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business Online

Authors: Charles Duhigg

Tags: #Psychology, #Organizational Behavior, #General, #Self-Help, #Social Psychology, #Personal Growth, #Business & Economics

“What do you do about the cat smell?” a scientist asked the woman.

“It’s usually not a problem,” she said.

“How often do you notice a smell?”

“Oh, about once a month,” the woman replied.

The researchers looked at one another.

“Do you smell it now?” a scientist asked.

“No,” she said.

The same pattern played out in dozens of other smelly homes the researchers visited. People couldn’t detect most of the bad smells in their lives. If you live with nine cats, you become desensitized to their scent. If you smoke cigarettes, it damages your olfactory capacities so much that you can’t smell smoke anymore. Scents are strange; even the strongest fade with constant exposure. That’s why no one was using Febreze, Stimson realized. The product’s cue—the thing that was supposed to trigger daily use—was hidden from the people who needed it most. Bad scents simply weren’t noticed frequently enough to trigger a regular habit. As a result, Febreze ended up in the back of a closet. The people with the greatest proclivity to use the spray never smelled the odors that should have reminded them the living room needed a spritz.

Stimson’s team went back to headquarters and gathered in the windowless conference room, rereading the transcript of the woman with nine cats. The psychologist asked what happens if you get fired. Stimson put his head in his hands. If he couldn’t sell Febreze to a woman with nine cats, he wondered, who

could

he sell it to? How do you build a new habit when there’s no cue to trigger usage, and when the consumers who most need it don’t appreciate the reward?

The laboratory belonging to Wolfram Schultz, a professor of neuroscience at the University of Cambridge, is not a pretty place. His desk has been alternately described by colleagues as a black hole where documents are lost forever and a petri dish where organisms can grow, undisturbed and in wild proliferation, for years. When Schultz needs to clean something, which is uncommon, he doesn’t use sprays or cleansers. He wets a paper towel and wipes

hard. If his clothes smell like smoke or cat hair, he doesn’t notice. Or care.

However, the experiments that Schultz has conducted over the past twenty years have revolutionized our understanding of how cues, rewards, and habits interact. He has explained why some cues and rewards have more power than others, and has provided a scientific road map that explains why Pepsodent was a hit, how some dieters and exercise buffs manage to change their habits so quickly, and—in the end—what it took to make Febreze sell.

In the 1980s, Schultz was part of a group of scientists studying the brains of monkeys as they learned to perform certain tasks, such as pulling on levers or opening clasps. Their goal was to figure out which parts of the brain were responsible for new actions.

“One day, I noticed this thing that is interesting to me,” Schultz told me. He was born in Germany and now, when he speaks English, sounds a bit like Arnold Schwarzenegger if the Terminator were a member of the Royal Society. “A few of the monkeys we watched loved apple juice, and the other monkeys loved grape juice, and so I began to wonder, what is going on inside those little monkey heads? Why do different rewards affect the brain in different ways?”

Schultz began a series of experiments to decipher how rewards work on a neurochemical level. As technology progressed, he gained access, in the 1990s, to devices similar to those used by the researchers at MIT.

Rather than rats, however, Schultz was interested in monkeys like Julio, an eight-pound macaque with hazel eyes who had a very thin electrode inserted into his brain that allowed Schultz to observe neuronal activity as it occurred.

2.21

One day, Schultz positioned Julio on a chair in a dimly lit room and turned on a computer monitor. Julio’s job was to touch a lever whenever colored shapes—small yellow spirals, red squiggles, blue lines—appeared on the screen. If Julio touched the lever when a shape appeared, a drop of blackberry juice would run down a tube hanging from the ceiling and onto the monkey’s lips.

Julio liked blackberry juice.

At first, Julio was only mildly interested in what was happening on the screen. He spent most of his time trying to squirm out of the chair. But once the first dose of juice arrived, Julio became very focused on the monitor. As the monkey came to understand, through dozens of repetitions, that the shapes on the screen were a cue for a routine (touch the lever) that resulted in a reward (blackberry juice), he started staring at the screen with a laserlike intensity. He didn’t squirm. When a yellow squiggle appeared, he went for the lever. When a blue line flashed, he pounced. And when the juice arrived, Julio would lick his lips contentedly.

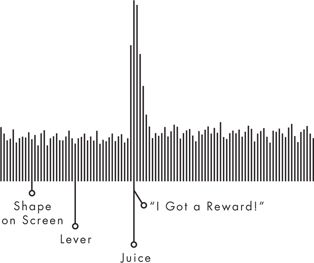

JULIO’S REWARD RESPONSE WHEN HE RECEIVES THE JUICE

As Schultz monitored the activity within Julio’s brain, he saw a pattern emerge. Whenever Julio received his reward, his brain activity would spike in a manner that suggested

he was experiencing happiness.

2.22

A transcript of that neurological activity shows what it looks like when a monkey’s brain says, in essence, “I got a reward!”

Schultz took Julio through the same experiment again and again, recording the neurological response each time. Whenever Julio received his juice, the “I got a reward!” pattern appeared on the computer

attached to the probe in the monkey’s head. Gradually, from a neurological perspective, Julio’s behavior became a habit.

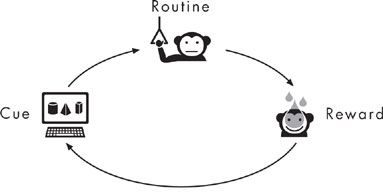

JULIO’S HABIT LOOP

What was most interesting to Schultz, however, was how things changed as the experiment proceeded. As the monkey became more and more practiced at the behavior—as the habit became stronger and stronger—Julio’s brain began

anticipating

the blackberry juice. Schultz’s probes started recording the “I got a reward!” pattern the instant Julio saw the shapes on the screen,

before

the juice arrived:

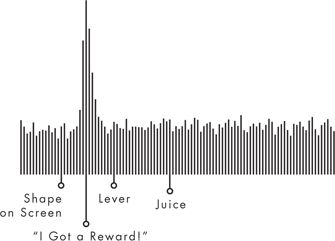

NOW, JULIO’S REWARD RESPONSE OCCURS BEFORE THE JUICE ARRIVES

In other words, the shapes on the monitor had become a cue not just for pulling a lever, but also for a pleasure response inside the

monkey’s brain. Julio started expecting his reward as soon as he saw the yellow spirals and red squiggles.

Then Schultz adjusted the experiment. Previously, Julio had received juice as soon as he touched the lever. Now, sometimes, the juice didn’t arrive at all, even if Julio performed correctly. Or it would arrive after a slight delay. Or it would be watered down until it was only half as sweet.

When the juice didn’t arrive or was late or diluted, Julio would get angry and make unhappy noises, or become mopey. And within Julio’s brain, Schultz watched a new pattern emerge: craving. When Julio anticipated juice but didn’t receive it, a neurological pattern associated with desire and frustration erupted inside his skull. When Julio saw the cue, he started anticipating a juice-fueled joy. But if the juice didn’t arrive, that joy became a craving that, if unsatisfied, drove Julio to anger or depression.

Researchers in other labs have found similar patterns. Other monkeys were trained to anticipate juice whenever they saw a shape on a screen. Then, researchers tried to distract them. They opened the lab’s door, so the monkeys could go outside and play with their friends. They put food in a corner, so the monkeys could eat if they abandoned the experiment.

For those monkeys who hadn’t developed a strong habit, the distractions worked. They slid out of their chairs, left the room, and never looked back. They hadn’t learned to crave the juice. However, once a monkey had developed a habit—once its brain

anticipated

the reward—the distractions held no allure. The animal would sit there, watching the monitor and pressing the lever, over and over again, regardless of the offer of food or the opportunity to go outside.

The anticipation and sense of craving was so overwhelming that the monkeys stayed glued to their screens, the same way a gambler will play slots long after he’s lost his winnings.

2.23

This explains why habits are so powerful: They create neurological cravings. Most of the time, these cravings emerge so gradually

that we’re not really aware they exist, so we’re often blind to their influence. But as we associate cues with certain rewards, a subconscious craving emerges in our brains that starts the habit loop spinning. One researcher at Cornell, for instance, found how powerfully food and scent cravings can affect behavior when he noticed how Cinnabon stores were positioned inside shopping malls.

Most food sellers locate their kiosks in food courts, but Cinnabon tries to locate their stores

away

from other food stalls.

2.24

Why? Because Cinnabon executives want the smell of cinnamon rolls to waft down hallways and around corners uninterrupted, so that shoppers will start subconsciously craving a roll. By the time a consumer turns a corner and sees the Cinnabon store, that craving is a roaring monster inside his head and he’ll reach, unthinkingly, for his wallet.

The habit loop is spinning because a sense of craving has emerged.

2.25

“There is nothing programmed into our brains that makes us see a box of doughnuts and automatically want a sugary treat,” Schultz told me. “But once our brain learns that a doughnut box contains yummy sugar and other carbohydrates, it will start

anticipating

the sugar high. Our brains will push us toward the box. Then, if we don’t eat the doughnut, we’ll feel disappointed.”

To understand this process, consider how Julio’s habit emerged. First, he saw a shape on the screen:

Over time, Julio learned that the appearance of the shape meant it was time to execute a routine. So he touched the lever: