The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership (32 page)

Read The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership Online

Authors: Yehuda Avner

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #Politics

I swallowed. “But there’s absolutely nothing German about you. You’re as Yankee as baseball.”

His mouth spread into a thin-lipped smile. “Me, a Yankee? I’m a German refugee kid in disguise, you jerk. I’ve been working at it all my life.”

“Then how come Kissinger has such a heavy accent and you’ve got none?”

“Because as a kid Heinz was shy and a bit withdrawn, and any speech therapist will tell you that shyness inhibits the ability to mimic, and you have to be a mimic like me to acquire accent-free fluency. Our indefatigable English teacher at George Washington High, Miss Bachman, tried with endless patience to rid Heinz of his Bavarian accent. ‘Henry, you have a chronic English-language speech disability,’ mimicked Willie impersonating Miss Bachman’s schoolmarm’s wheedling voice. ‘You must try harder to Americanize it.’”

“So when did Furtwangler become Fort?” I asked.

“The day I graduated medical school. It was an obvious choice.”

To prove it he formed his mouth into an oval and, with a long, drawn-out breath, exhaled the name F-U-R-T-W-A-N-G-L-E-R, and then ‘F-U-R-T-H,’ each time exaggerating the guttural ‘R’ and the spiked umlaut.

“Get it? Wilhelm Furtwangler from Furth morphs into Willie Fort from Washington.”

As he acted out this nomenclature I tried to rethink his life story, and he, as if reading my mind, said with amused contempt, “And now Heinz is the American secretary of state. When Nixon appointed him in seventy-three, I sent him a congratulatory note with an old photo of him holding up the football I’d given him for his bar mitzvah. He was crazy about football as a kid. But do you think he acknowledged it? Not a chance!”

“Were you that close as boys?”

A glint of fond reminiscence entered his eyes and he chuckled at the thought of it: “There was no one closer. Even though he was a bit of a bookworm and I wasn’t, we had great times together. We sometimes even got our ears boxed for fooling around.”

“And what happened when the Nazis came?”

Willie let the reminiscences flow like unstoppable water through the cracks of a dam: “When the Nazis came our neighbors told our parents not to worry: Hitler was just another anti-Semitic street brawler disseminating mad propaganda, best ignored. But gradually they changed their tune and said, look at the good things Hitler was doing for Germany. And soon after that we weren’t allowed to play with their children anymore, and Heinz’s father lost his prestigious job as a State school teacher, and we were expelled from the State-run high school and had to go to a special Jewish school, and we weren’t allowed to go to football matches, so we set up our own soccer team, and we weren’t allowed to go to the municipal swimming pool, and we weren’t allowed to go anywhere where it said ‘Juden Verboten! ’ And the Gestapo came banging on our doors, and the Hitler Youth beat us up. And so we ran away until we reached America.”

Gripped with such dark memories, Willie’s usually bright demeanor slumped into melancholy. He rose and said, “I need fresh air. I’m going for a walk.”

Outside, the ceaseless hum of traffic along King David Street was punctuated by the sharp tongue of an angry cab driver shouting at an Israeli security guard whose car was occupying his spot in the hotel’s taxi rank. Two other taxi drivers, ignoring the row, were idly playing cards, while well-dressed, muscular American security agents with crewcuts lolled about the driveway, maintaining a watch.

“Let’s walk,” said Willie, as if hoping the breeze and the sun would wash away the brooding hurt. But since I had nothing worthy to say he had only his pain for company. He took a seat on a bench overlooking the Old City walls, and said contemplatively, “It’s so complicated, so very complicated.”

“What is?”

“Kissinger. He’s trying so hard to repress his feelings, he’s obsessed by them. The years of Nazi persecution are locked deep inside him.”

There was an expression of sympathy in Willie Fort’s voice intermingled with a sort of frustration, which explained itself when he added, “I’m speaking professionally, as a psychiatrist. I believe he needs help.”

“What sort of help?”

“Psychiatric help. There are basic tensions in that man’s psyche which influence how he perceives the world and, consequently, how he arrives at his decisions. There’s no separating his personality from his policies.”

This was an intriguing and unsettling thought, so I asked Willie to elaborate.

“By all means,” he said. “I shall offer you an off-the-peg, extemporaneous psychoanalysis of Henry-Heinz Kissinger, based on reliable hearsay and anecdotal observations, and shared by many of my professional colleagues. You might wish to write some of this down. It could be of interest to your prime minister.”

I took out my pen and prepared to write.

Henry Kissinger, he said, habitually insisted he had no lasting memories of his childhood persecutions in Germany. This was nonsense! In 1938, when Jews were being beaten and murdered in the streets, and his family had to flee for their lives, he was at the most impressionable age of fifteen. At that age he would have remembered everything: his feelings of insecurity, the trauma of being expelled, of not being accepted; what it meant to lose control of one’s life, to be powerless, to see one’s beloved heroes suddenly helpless, overtaken by brutal events, most notably his father, whom he greatly admired and who was expelled from his prestigious teaching post, leaving the family devastated. Those demons would never leave Henry Kissinger, however hard he tried to drown them in self-delusion.

Outwardly, the secretary of state presented an image of self-assurance, strong will, and arrogance, Willie went on. Inwardly, however, because of his suppressed emotions and state of denial, he was possessed of a deeply depressive disposition, an apocalyptic view of life, a tendency to paranoia, and an excessive sense of failure when things did not go his way. Typically, such inner doubts triggered displays of petulance, tantrums, and temper. Persons of such a nature were invariably overly solicitous of their superiors and overly harsh toward their subordinates. They had an excessive need to be loved and admired, and an extreme ambition to excel.

Henry Kissinger’s Jewishness was equally a source of neurosis, according to Willie Fort. Reared as a deeply observant Jew, Kissinger slipped away from beneath the Orthodox shadow of his parental home when he was drafted into the American army in 1943. His rebellion was absolute and his assimilation total. Yet, try as he might, Henry Kissinger would never be able to shed his thin Jewish refugee skin.

Willie emitted a sudden cynical laugh, and observed, “I’ve learned through the White House grapevine that whenever Nixon feels Kissinger is getting too big for his boots he is not averse to resorting to nasty anti-Semitic barbs to cut him down to size. He has even been known to call him ‘my Jew boy’ to his face. And he takes a perverse satisfaction in humiliating and taunting him with anti-Semitic slurs about how the Jews put Israel’s interests ahead of America’s, and how cliquey they are, wielding far too much power because of their wealth, and too much influence because of their control of the media, things like that. It is said that Kissinger is careful not to bring Jewish staff members to meetings with the President for fear of arousing his anti-Semitic streak. And when it is aroused he pretends to shrug it off, concealing his humiliation, but then, back in the privacy of his room, he invariably goes into a tantrum and takes it out on his subordinates.”

“So how does this impact on his role as mediator between us and the Arabs?” I asked.

“People like him invariably over-compensate. They go to great lengths to subdue whatever emotional bias they might feel, and lean over backward in favor of the other side to prove they are being even-handed and objective.” And having said that, Willie sprang suddenly to his feet, his old buoyant self again, and strolling back to the hotel rounded off his extemporaneous diagnosis thus: “What happened in the King David lobby suggests that our brilliant American secretary of state

–

forty-fourth in line since Thomas Jefferson

–

behaved in a neurotic fashion. One minute he was glorying in the world’s spotlight at his press conference, and the next, when he saw me, he was hurtled back into Jewish memories he’d spent a lifetime trying to suppress. He certainly recognized me. You noted how he bridled at my mention of his name, Heinz. He utterly despised me for that. So yes, I have to conclude that the man is disturbed. Tell Yitzhak Rabin he should be most wary in dealing with our secretary of state. Tell him that deep inside him is an insecure and paranoid Jew.”

A few hours later Air Force One lifted off from Ben-Gurion Airport carrying the president and his secretary of state back home to Washington

–

and to Watergate. After seeing them off with all due ceremony, Prime Minister Rabin traveled back to Jerusalem to hold a press conference of his own at the King David Hotel, where he assessed the positive significance of the visit and the boost it had given to the U.S.-Israeli relationship.

Asked by the German correspondent what, in his view, had brought about the Arab tilt toward Washington and away from Moscow, Rabin answered categorically: “The reason is President Nixon’s policy of keeping Israel strong, by giving us the means to defend ourselves by ourselves. Ever since the airlift of the Yom Kippur War, the Arabs have come to understand that America will not allow Israel to be weakened. A defeat of Israel is a victory for the USSR. Paradoxically, this is what has raised America’s prestige in the Arab world, and has given Washington leverage. Today in the Middle East, Moscow is a synonym for instability and war, Washington for stability and negotiation.”

“But is there not a negative aspect to this change from your standpoint?” asked a reporter from the

New York Times

.

“What sort of negative aspect?”

“A few hours ago, in this very room, Dr. Kissinger told us that America no longer stands exclusively on the side of Israel. Does that not do something to diminish the U.S.-Israel relationship?”

“The opposite is true,” contended Rabin. “Not only have the relations not been diminished, our friendship and cooperation have grown.” But then he paused, and after a moment’s reflection, added with his typical candor: “I must confess it is only natural that in certain aspects there is concern for the loss of the pre–Yom Kippur War exclusivity in the Israel-U.S. relationship. But we have to acknowledge that we are living in changed circumstances, and it is impossible to remain oblivious to those changes. So now we must seek the greatest possible benefit from them. This means our ability to utilize the closer Arab association with the United States in order to initiate new political movement toward a peace, with America serving as an honest broker. This can’t be done by a single act such as a peace conference. It is a phased, patient, step-by-step process.”

35

It pleased Rabin shortly thereafter to hear from Kissinger that President Nixon had said much the same in a letter to President Sadat, penned on 25 June, shortly after his visit to Cairo, in which he wrote:

…As a result of our talks each of us has a better understanding of the other’s concerns, hopes and political realities. I particularly welcomed the opportunity to describe to you our concept of approaching a final settlement step-by-step, so that each succeeding step will build on the confidence and experience gained in the preceding one…. Mr. President, I am convinced that we have witnessed in recent months a turning point in the history of the Middle East

–

a turning toward an honorable, just, an endurable peace

–

and have ushered in a new era in U.S.-Arab relations. A direction has been set, and it is my firm intention to stay on the course we have charted.

36

But the American people had other ideas for President Nixon’s course for the future. Even as he was putting his signature to this diplomatic note in the privacy of his Oval office, the House Judiciary Committee was conducting public impeachment proceedings against him on Capitol Hill. And the deeper the committee probed, the deeper Mr. Nixon ensnared himself in his Watergate morass, so that by the end of August he threw in the towel and did what no other American President had ever done before: he resigned.

Vice President Gerald Ford entered the White House in Nixon’s stead, and being a total neophyte in international affairs, he promptly picked up the phone to Dr. Kissinger, and said, “Henry, I need you. The country needs you. I want you to stay. I’ll do everything I can to work with you.”

“I thank you for the trust you place in me, Mr. President,” answered an elated secretary of state, and when he replaced the receiver he felt more alive than he had ever felt before, knowing that he was now virtually sovereign in setting the course of American foreign policy.

37

One of his first acts was to recommend to President Ford that he invite Prime Minister Rabin to Washington to discuss the next step.

Yeduha

The prime minister and his advisers arrived in the American capital on 10 September 1974, and the talks generally went well. All agreed that a comprehensive settlement was too utopian to contemplate at this stage, and that the best way forward was to continue the step-by-step approach. Rabin, however, expressed one important reservation. He told Ford and Kissinger, “I’m facing considerable criticism back home regarding my step-by-step approach, not least from the leader of our opposition, Mr. Begin. Begin argues that withdrawals without peace ruin the very chances of peace. Peace, he contends, will be advanced only when we adopt a policy that leads to overall serious peace commitments, not mere disengagements or partial settlements. I take serious note of this. If we go ahead giving up a piece of land without getting a piece of peace in return, we’ll end up squandering everything without gaining anything. Hence, it is imperative that any future step of withdrawal on our part be recompensed by a political step toward peace on the part of the Egyptians.”

The president and the secretary of state had no argument with that, and it was decided that Kissinger would soon revisit the region to examine the feasibility of this course.

Rabin’s Washington visit ended in the grandest of styles. President Ford

–

a tall, affable, athletic-looking fellow in his early sixties

–

hosted an official state banquet in his honor. It was a sumptuous and

extravagant

affair that took place in the State banqueting hall. From his gilded frame above the fireplace Abraham Lincoln looked down on more than two hundred black-tied and opulently gowned guests sitting at round tables in the historic room, as exalted as a museum gallery that emanated power, influence, and fortune. Elongated amber mirrors reflected the enormous, shimmering brass chandelier at the ceiling’s center, casting a pleasing flaxen light over the entire setting. Two ushers opened double doors and heralded the entry of twenty violinists, all attired in the crimson dress uniform of the Marines Corps. Two by two, their bows rising and falling in perfect synchronization, they advanced down the center aisle playing an emotive medley of Israeli tunes. An embossed card present at each table explained that these musicians belonged to the strings section of the Marine Chamber Orchestra which, itself, was a part of the famed Marine Band, America’s oldest musical organization, established by an Act of Congress in 1798, and traditionally called “The President’s Own.”

A tableau of animated faces watched President Ford rise to welcome his guests and to say to Rabin by way of introduction, “As I was sitting here chatting with you and Mrs. Rabin, I couldn’t help but note that nineteen forty-eight was a somewhat significant year as far as your country is concerned. And it just so happens, it was quite a year for the Fords, too. It was the year we got married.”

“So did we,” called out Leah Rabin, to laughter and applause.

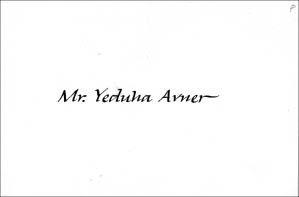

Toasts followed a predictable script, host and guest of honor lauding each other’s enduring friendship, eternal alliance, and common values, after which, at an unseen signal, liveried butlers fanned out across the room, each bearing feasts of roasted pheasant, sizzling roast potatoes, and decorative garnished beans. Soon, everybody was chomping on their succulent fare except me. I had pre-ordered a vegetarian kosher dish which, for some reason, tarried. Perhaps it was because my place card had been misspelled: instead of “Yehuda” it was engraved “Yeduha Avner.”

A couple of chairs away the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General George Brown, was chatting with Barbara Walters, the famous television celebrity, who was sitting on my right. Within minutes, the general caught sight of my still-empty place setting and, craning his neck to note my name card, boomed, “Yeduha, not eating with us tonight?” Whereupon, as if on cue, a butler stepped forward and placed before me a vegetarian extravaganza consisting of a base of lettuce as thick as a Bible, on top of which sat a mound of diced fruit, on top of that a glob of cottage cheese, and on top of that a swish of whipped cream, so that the whole

thingamajig

must have stood about a foot high. In contrast to everybody else’s deep brown roasted pheasant, it glittered and sparkled like a firework.

Gasps of admiration greeted this fiesta of color, and Barbara Walters began to applaud. This attracted the attention of President Ford who, half rising to see what the commotion was about, whispered something into Yitzhak Rabin’s ear, who whispered something back into his. Then, rising to his full height and grinning from ear to ear, the president raised his glass high and called out to me with an overflow of well-being, “Happy birthday young fella! Let’s sing a toast to our birthday boy.”

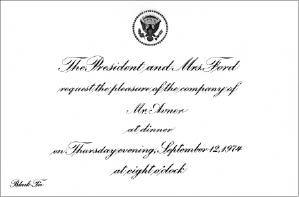

White House dinner invitation

Author’s misspelled table card at White House Dinner

With that, the entire banqueting hall rose to its feet and, goblets aloft, chorused a hearty, “Happy birthday dear Yeduha.” And as they sang I slouched sheepishly further into my chair, mortified.

In the ballroom after dinner I asked Rabin why on earth he had told the President it was my birthday, and he shot back, “What else should I have told him

–

the truth? If I did that, tomorrow there’d be a headline in the newspapers that you ate kosher and I didn’t, and the religious parties will bolt the coalition, and I’ll have a government crisis on my hands.

Ani meshuga?

Am I crazy?” And then, with a sudden startled gaze, “Oh my God, look at that! What am I supposed to do now? Save me somebody!”

He was watching as a beaming President Ford swept Leah Rabin onto the brightly lit ballroom floor and waltzed her around to general applause, while an expectant First Lady Betty Ford flashed a smile at Rabin, awaiting his invitation to follow suit. With nowhere to run he grimly made his way toward Mrs. Ford as if walking the plank, bowed awkwardly, and croaked, “Please forgive me, I can’t do it.”

“Can’t do what?”

“Can’t dance.”

“Can’t dance?” The woman seemed astounded, as if she had never heard of such a thing.

“Not a step,” blushed the prime minister. “I’ll be treading on your toes all the while. I’ve tried it before. I’m no good at it.”

“Have no fear, Mr. Prime Minister,” chortled a buoyant Mrs. Ford, taking him by the hand and leading him onto the ballroom floor. “When I was younger I used to teach dance, and I protected my toes from men far less skillful than you. Now this is how you do it: put your hand here. That’s right. And your other hand here. Very good! And now relax, and let’s go: one-two-three; one-two-three; one-two-three. Excellent! You’re doing fine, getting the hang of it!” and she rotated the crimson-faced premier around and around, he staring fixedly at the First Lady’s toes until

Dr.

Kissinger

–

himself no swinger

–

tapped him on the shoulder, and said in deadly seriousness, “Yitzhak, give up while you’re ahead. Let me take over. Mrs. Ford, may I have this dance?”

“By all means,” said she, letting go of Rabin, who tottered toward his chuckling staffers, muttering, “If Henry Kissinger does nothing else for Israel but save me from that embarrassment I shall be forever in his debt.”

A few months later, in March 1975, Secretary of State Kissinger returned to the Middle East to test the political waters, embarking on a remarkable odyssey unheard of in international relations. It was dubbed shuttle diplomacy

–

a whirlwind, improvised to and fro between Egypt and Israel to badger Rabin and Sadat into negotiating the next step. In a marathon schedule that created convoluted complications of timing, Kissinger would arrive in Jerusalem at abnormal hours of the day and depart for Cairo at eccentric hours of the night. He flitted back and forth in an antiquated Boeing 707 which had been Lyndon Johnson’s plane when he was Kennedy’s vice president.

Since the talks were held at all hours of the day and the night, and frequently in haste, people’s nerves easily frayed. Rabin soon felt he was being unduly pressured, sensing that Kissinger was cajoling him into accepting an

IDF

withdrawal in Sinai deeper than he was prepared to concede in return for an Egyptian step toward peace smaller than he was ready to accept. In short, he felt Henry Kissinger was seeking a deal at almost any price to demonstrate to the Egyptian president that America alone could deliver Israel.

The indefatigable secretary of state conjured up concessions and trade-offs, wheedling, rhapsodizing, hectoring, threatening, and sometimes going out of his way to charm his hosts with jokes against himself as a means of relaxing tensions. At one such session a furious row broke out over Rabin’s incessant insistence that Sadat give him something politically substantial in return for a sizeable

IDF

withdrawal in Sinai, just as he had advocated in Washington. He wanted the Egyptian president to commit himself once and for all to a “termination of the state of belligerency” with the Jewish State.

“Sadat will never accept such language,” flared Kissinger. “It would be tantamount to his acknowledging the end of the state of war while your army still occupies huge swathes of his territory. The furthest I might persuade him to go is a commitment to the ‘non-use of force’ in return for your

IDF

pull-back.” But Rabin refused to budge, and his obduracy drove Kissinger berserk. The ever-composed Joe Sisco, Kissinger’s chief deputy, proposed a recess, and the legal advisers were brought in to try and come up with some ingenious linguistic compromise. While they were at it, Kissinger, poking fun at himself in an effort to reduce tensions, said, “Yitzhak, you have to understand that since English is my second language I may not always grasp its nuances. When I arrived in America it took me a while before I understood that maniac and fool were not terms of endearment. And, only recently, I offered to teach English to the Syrian President Hafez al-Assad. I told him, if you would allow me to teach you the language, you would be the first Arab leader to speak English with a German accent.”

Such self-effacing wit

–

something Rabin himself did not possess

–

did succeed in bringing temperatures down, and the talks resumed in a less heated spirit.

In those shuttle days, the media could not get enough of Henry Kissinger. Headlines catapulted him to superstardom, crediting him with the ability to perform deeds unheard of in contemporary diplomacy. This man crafted the doctrine of detente with the USSR, nudged Moscow to the arms control negotiation table, paved the way for Nixon to China, brokered the first disengagement deal between Egypt and Israel, and then between Syria and Israel after the Yom Kippur War, and coerced Hanoi into the Paris peace talks, opening up the prospect of an honorable U.S. exit from Vietnam.

Wherever he traveled, the international press followed in droves. The most privileged were the “Kissinger 14”

–

so nicknamed because they were the senior Washington correspondents for whom the fourteen seats in the extreme rear section of the secretary’s aging aircraft were reserved. And though having to put up with much discomfort in flight, they alone were privy to the secretary’s midair, off-the-record, not-for-attribution deep briefings, given under the thin disguise of a “senior official.” These fourteen were more familiar with Kissinger’s inner thoughts than most of the Israeli officials who dealt directly with him. This I knew because I was acquainted with most of the “14” from my Washington and foreign press bureau days, and occasionally pumped them for information myself.

Late one night, seven of the “14” straggled into the King David Hotel’s coffee shop, where I was passing the time with other correspondents. They had just arrived with Kissinger from Cairo for the umpteenth time (the shuttle had begun on 8 March and this was 21 March). They were

NBC

’s Richard Valeriani,

ABC

’s Ted Koppel,

CBS

’s Bernard Kalb, the

Washington Post

’s Marlyn Berger, the

New York Time

’s Bernard Gwertzman,

Time

’s Jerrold Schecter, and

Newsweek

’s Bruce van Voorst. All had the jet-lagged, haggard look of long-distance flyers. As they shuffled in, bleary-eyed and weary, the jaded correspondents already slouching in the coffee shop, bored for lack of news, offered them their chairs in the hope of picking their brains. I, too, was intent on acquiring information, with the aim of passing on to Rabin whatever useful tidbits might come my way.

One lean Londoner from the

Daily Telegraph

, spotting a badge on Richard Valeriani’s lapel, called out, “Hey Dick, what’s that badge you’re wearing?”