The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership (33 page)

Read The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership Online

Authors: Yehuda Avner

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #Politics

The tall, gangling

NBC

man responded by throwing him a mischievous grin, and turned to all corners of the room so that all present could clearly see his lapel, onto which a campaign-style button was pinned. All were in fits of laughter as they read:

“

FREE THE KISSINGER 14

.”

This show of camaraderie triggered colossal applause, and as it soared a fellow with a camera clicked and shouted, “Hey, you ‘14,’ is it true that King K. has confided to you, not for attribution, that President Ford is alive and well after all, but he’s just fast asleep?” Another wisecracked: “And is it true that Mr. Fix-it spills you ‘14’ so many beans his plane is flying on natural gas?” And a third called out, simply, “Will there be an agreement, yes or no?”

A different pitch then took hold as the other journalists crowded around the seven, pressing them with specific questions: Was Rabin truly refusing to surrender the Mitla and Gidi passes in the Sinai desert? Was he still insisting on his “termination of belligerency” formula in return for a deep withdrawal? Was Kissinger truly threatening to fly back to Washington if Rabin refused to compromise, blaming Israel for the failure of his mission?

The overwrought tone of these questions faithfully reflected the mood pervading the smoke-filled conference room at the prime minister’s office, with exhausted negotiators vainly seeking to break the impasse into which they had floundered. When I entered, Henry Kissinger was shoving a map across the table at the prime minister, and grumbling, “For God’s sake, Yitzhak, draw me a final line to show how far you are prepared to pull back in Sinai. Whenever I go to Sadat, he’s ready with his answers on the spot!”

Rabin, with deliberate emphasis, responded, “Henry, unlike Egypt, Israel is a democracy. I will not be dictated to. Those passes hold the key to an Egyptian invasion of Israel. You will get the final line only after I get final approval from the cabinet.”

“And how long will that take?” asked Kissinger scornfully.

“The last cabinet session lasted ten hours,” returned Rabin, provocatively.

Kissinger threw down his pen. “You know what? I no longer care. Do with the map whatever you want.”

There was a sudden silence: no movement, not even the whisper of a sound, until the door gently opened and in walked an American security agent. He approached the secretary of state reverentially, and whispered, “You left these in the car, sir.”

He was holding a pair of spectacles.

Kissinger glowered at him in contempt, as if to say, how dare you approach the secretary of state without permission?

Humiliated, the security agent froze, the spectacles in his hand, not knowing what to do with them. U.S. Ambassador Kenneth Keating came to his aid by relieving him of the glasses, leaning across the table to hand them to Joseph Sisco who, in turn, handed them to Dr. Kissinger. The hierarchy of protocol thus preserved, the secretary pocketed his spectacles, gathered up his papers, muttered, “I’m off” and moved toward the door, his features downcast, knowing his mission had failed.

“Henry!”

It was the charged, deep voice of Yitzhak Rabin.

Kissinger turned. The two men’s eyes locked.

“You know very well we have offered a compromise at every step along the way,” fumed Rabin. “You know we have agreed to adopt your language on the ‘non-use of force,’ which means much less than a ‘termination of belligerency.’ You know we have agreed to hand over the Sinai oil fields. You know we have agreed, in principle, to pull back as far as the eastern end of the passes. You know we have agreed to allow the Egyptian army to advance from its present positions and occupy the buffer zone. And you know we have agreed that they may set up two forward positions at the western entrances to the passes. After all this display of goodwill and flexibility for the sake of the success of your mission

–

and at great risk to ourselves

–

to then accuse us of causing the failure of your mission, instead of laying the blame on Sadat’s intransigence, is a total distortion of the facts.”

Kissinger listened, turned, and without another word walked out of the room. The Israeli negotiating team

–

which included Defense Minister Shimon Peres, Foreign Minister Yigal Allon, and Ambassador Simcha Dinitz

–

exchanged shocked looks. Instantly, Rabin picked up a phone and instructed his assistant to call the cabinet into emergency session. In the course of that session, a courier arrived with an urgent message from President Gerald Ford. Rabin read out the message to his ministers. It said:

Kissinger has notified me of the forthcoming suspension of his mission. I wish to express my profound disappointment over Israel’s attitude during the course of the negotiations. From our conversations, you know the great importance I attached to the success of the United States’ efforts to achieve an agreement. Kissinger’s mission, encouraged by your Government, expresses vital United States interests in the region. Failure of the negotiations will have a far-reaching impact on the region and on our relations. I have given instructions for a reassessment of United States policy in the region, including our relations with Israel, with the aim of ensuring that our overall American interests are protected.38

This was about as brutal a message as diplomatic dispatches get, and the cabinet ministers listened to it in dry-throated silence, weighing each word with the same intensity that its author had put into its drafting. There was no doubt in Rabin’s mind who that author was, just as his ministers had no doubt that it heralded the gravest of possible crises between the two countries. Gloomily they discussed consequences, and they were in the midst of their pessimistic assessments when an assistant entered to inform the prime minister that Kissinger was on the line asking if he could come over right away.

Rabin received him in his inner sanctum, where the secretary of state, breathing heavily, tried hard to retain his composure.

“Yitzhak, I want you to know I had nothing to do with the President’s message,” he said.

Rabin, lighting a cigarette, glared at him through the flame of his lighter, and said, “Henry, I don’t believe you. You asked the President to send that message. You dictated it yourself.”

Kissinger, shocked, began shouting, “How dare you suggest such a thing? Do you think the president of the United States is a puppet and I pull his strings?”

Rabin did not answer. He just stood there in stony silence.

Kissinger, beside himself with frustration and rage, yelled, “You don’t understand, I’m trying to save you. The American public won’t stand for this. You are making me, the secretary of state of the United States of America, wander around the Middle East like a Levantine rug merchant. And for what

–

to bargain over a few hundred meters of sand in the desert? Are you out of your mind? I represent America. You are losing the battle of American public opinion. Our step-by-step doctrine is being throttled. The United States is losing control of events. There will be insurmountable pressure to convene a Geneva conference with Russia sharing the chair. A war might break out, the Russians are going to come back in, and you’ll have to fight without an American military airlift because the American public won’t support one.” Then, tantrum full-blown: “I warn you, Yitzhak, you will yet be responsible for the destruction of the third Jewish commonwealth.”

Rabin, red in the face, hurled back, “And I warn you, Henry, you will be judged not by American history but by Jewish history!”

The following morning the two men

–

longtime friends and longtime adversaries

–

closeted themselves in a room at Ben-Gurion airport and, according to what Rabin later told us, had an extremely emotional exchange. Rabin once again told Kissinger exactly what he felt

–

that though he fully realized the new situation could deteriorate into war, Israel could compromise no further. This was not just a matter of acute political consequence to him as prime minister, but, equally, of acute anxiety to him as a man, for he felt personally responsible for every

IDF

soldier, as though they were his sons. Indeed, at that very moment his own son was serving on Sinai’s front line, in command of a tank platoon, as was his daughter’s husband, who commanded a tank battalion, and he knew what their fate might be in the event of war.

“And how did Kissinger react to that?” we asked him.

“I’ve never seen him so moved,” responded Rabin. “He may have wished to reply but his voice was so cracked with emotion he couldn’t. It was time to go out to his plane where we both were to make brief farewell statements. When it came to his turn he was so full of emotion he could hardly speak. Besides being upset at the failure of his mission I could see his inner turmoil, as a Jew and as an American.”

39

Once airborne, the secretary of state made his way to the rear of his aircraft to brief the “14,” as was his wont. He told them, ‘not for attribution,’ that Israel was to blame for the breakdown of the negotiations; that the failure of his mission would inevitably radicalize the Middle East; that war was now likely and, with it, an oil embargo; that the Egyptian and Syrian post–Yom Kippur War disengagement agreements would collapse; that the mandate of the United Nations forces deployed under those agreements would not be renewed; that Russia would replace America and again become the dominant force in the Middle East; that Europe would turn its back totally on Israel; that Russia and the Arabs would rush to convene an international conference at Geneva, leaving America without a policy and Israel without an ally; and that American public opinion would swing against Israel for having squandered the one chance of an interim agreement

–

a chance that had taken a year-and-a-half to germinate.

Hearing this from Rabin, who had heard the story from one of the journalists on the plane, I recalled Professor William Fort’s conjectures about the convoluted psychological profile of Dr. Henry Kissinger – his tendency to overreact when things did not go his way, his penchant for petulance and tantrum when crossed, his Machiavellian manipulations, and his innate inclination to bend over backward in the name of a spurious objectivity.

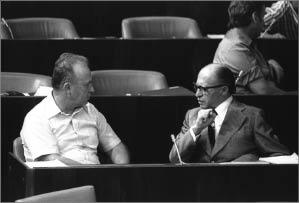

Photograph credit: Moshe Milner & Israel Government Press Office

Prime Minister Rabin with leader of the opposition Menachem Begin, 3 September 1975

Collusion at Salzburg

Like a concert audience come to hear a classical recital, the journalists in the press gallery of the Knesset chamber stirred with anticipation as Yitzhak Rabin stepped down from the podium having given a dry, matter-of-fact report on the crumbled negotiations with Egypt, and Menachem Begin stepped up to respond. This oratorical virtuoso, whose mastery of style and pace could grasp and command any gathering, got off to a flying start when he fixed Rabin in his determined gaze, and said to him in a schoolmasterly voice:

“Mr. Prime Minister, I would have wished that you and your colleagues had refrained from insisting on the use of the expression ‘termination of belligerency.’ It stems from the Latin

bellum ger

o

, and its practical meaning is so vague and obscure that nobody really understands what it legally implies.”

Cries of offense and defense rose from the benches, stretching from wall to wall.

“The point I am making, Mr. Speaker,” pressed Begin, cutting through the clamor and stabbing a finger at the government benches, “is this: why ask for something so nebulous as a ‘termination of belligerency’ when you should have been demanding an end to the state of war?”

Again, cries for and against swept the House floor, and Begin switched tone from stern hammering to thunder:

“Yes, that’s right, you understand me well. I’m talking about a peace treaty. No withdrawal in Sinai without a peace treaty. And the first clause of any peace treaty speaks not about the termination of belligerency but about the cessation, the termination, of the state of war, plain and simple. It should, therefore, be made clear to all free nations, and most particularly to our American friends, what our enemy’s intentions truly are

–

his refusal to end the state of war even in return for a deep IDF withdrawal and even after further and ever-deeper IDF withdrawals.”

Rabin sat listening, the expression on his face difficult to parse. I knew he was deeply anxious. It was a stalemate, and pessimism filled the air around him. To get through it he needed a show of national unity; he needed to display to Gerald Ford and Henry Kissinger that the nation stood squarely behind him. Hence, his one concern during that moment was not Begin’s remonstrations, but whether, at the end of the debate, he would support the government’s actions or not.

Like a cavalry horse answering the bugle, Begin continued galloping headlong into the fray, flinging an arm in a sweeping arc as he denounced what he called “the prime minister’s excessive concessions for the sake of a so-called interim agreement which, were it to be carried out, would fritter away the country’s security in return for war and more war.”

Rabin’s angry supporters began bawling epithets so shrill that the Speaker, a gaunt, self-effacing, gentle man, banged his gavel over and over again, shouting all the while “Order! Order!” No one paid attention. So Begin stood there patiently, waiting for the din to run its course, whereupon, he again addressed Rabin, but this time with a degree of empathy.

“Mr. Prime Minister,” he said reassuringly, to a now totally silent chamber, “even after the grave charges I’ve laid against you in your having vainly tried to exchange Sinai for something much less than peace, I say now, given the seriousness of the situation in our relations with America and, perhaps even the danger of war, I deem it a propitious hour for us all to display national unity.”

Involuntarily, a flicker of a smile rose at the edges of Rabin’s mouth, and a buzz of approval spread around much of the hall. The support of this complex, shrewd, iron-willed leader of the opposition would surely give pause to the American president and his secretary of state as they pondered their “reassessment” policy to punish Israel.

“Under no circumstances is your government to be blamed for the failure of these negotiations,” continued Begin, his right hand held out as if he wanted to shake that of the prime minister’s. “Responsibility for the failure of Dr. Kissinger’s mission is Egypt’s alone.”

And then, with a thump of the podium, jaw jutting, he snarled, “The Egyptians have had the effrontery to treat us as though we were the defeated nation and they the victors, demanding we accept their dictates. The chutzpah of it! Thank God the government put a stop to it, and from the moment it did, our nation has straightened its back so that we stand tall once more, confident in the moral justice of our cause. American and world Jewry will surely stand by us in this hour of crisis, together with our many other American friends, be they in Congress or elsewhere. Indeed, good people of goodwill everywhere will stand by us and lend us support.”

He paused once more as if gathering himself, and his next sentence resounded around the chamber like a clarion call:

“Mr. Speaker, ladies and gentlemen of the Knesset: we of the opposition shall stand united with the government in facing whatever challenges lie ahead so that, with the help of He who brought us out of the house of Egyptian bondage and led us here to Eretz Yisrael, we shall emerge victorious together.”

As he stepped down from the dais and made his way through the crowded aisle, accepting congratulations on his speech from Knesset members who pressed forward to shake his hand, Yitzhak Rabin intercepted him by the cabinet bench. He extended his hand, and with a lopsided smile, said, “It takes true leadership to do what you just did, Begin. I thank you for that.”

“It was my simple duty,” responded the opposition leader with immense formality. But then, he smiled, and added teasingly, “And now it is your turn to perform an act of unusual national leadership. Go up to the podium and announce for all the world to hear that in this hour of national unity you, as prime minister, call upon the youth of Israel to volunteer to establish new settlements throughout the whole of our homeland

–

to settle all the waste places of Eretz Yisrael.”

Rabin smirked. “I know exactly what you’re after,” he said, “you’re after my job.”

“Exactly,” bantered Begin, “and as soon as possible.” But then, in all seriousness, “The truth is, if we don’t fill up the barren areas of Yehuda and Shomron with our settlements they will be occupied one day by that terrorist murderer Yasser Arafat and his so-called

PLO

. Then every Israeli town and village will be in range of their guns.”

In his reply, irritation burst through Rabin’s usually guarded tone: “You know very well where I stand,” he said. “The West Bank is our one bargaining chip for a future peace with the Palestinians. Fill it up with settlements and you destroy the very hope of peace.”

Resignedly, Begin responded, “Mr. Rabin, you go your way and I’ll go mine, and may the Almighty spread his tent of peace over us all.”

40

Some two months into the battle for American public opinion, Yitzhak Rabin, full of spirit, and euphoric, strode into my office waving a piece of paper, and exclaimed, “Take a look at this – a gift of the gods from Congress! Our campaign is bearing fruit.”

It was a cable from our Washington Embassy, citing an open letter addressed to President Ford and signed by seventy-six senators urging the president to support Israel in any future negotiation on an interim settlement with Egypt. It said:

“We urge you to make it clear, as we do, that the United States, acting in its own national interests, stands firmly with Israel in the search for peace in future negotiations, and that this premise is the basis of the current reassessment of U.S. policy in the Middle East.”

41

“Ford and Kissinger won’t like this one bit,” gloated Rabin, in a rare show of glee. “We have to thank the American Jewish organizations for this, particularly

AIPAC

.”

[1]

Had Rabin been able to gaze into a crystal ball that day, and divine what the American president would say to the Egyptian president about that letter a week later, on the second of June, he would have been far less sanguine. “The importance of that letter,” Ford told Sadat, “is being distorted out of all proportion. Half of the senators didn’t read it, and a quarter didn’t understand it. Only the additional quarter knew what they were doing. The impact of the letter is negligible.”

The president said this when he and Kissinger met with Sadat and his foreign minister, Ismail Fahmi, at the Residenz, a baroque edifice in the heart of “Old Town” Salzburg, Austria. They were sitting in a high-ceilinged parlor whose walls were hung with majestic portraits of royal Hapsburgs and church eminences, relics of a time when Salzburg was an ecclesiastical state and when the Residenz was the archbishop’s seat of governance. Now it was an official guest house.

What had brought the Americans to Europe was a

NATO

summit, and what led the Egyptians to rendezvous with them at this place with its spectacular Alpine view was a desire to revisit the possibility of an interim Sinai agreement.

In the course of the Egyptian-American deliberations a number of new ideas were put on the table to sweeten the terms so as to make an agreement more palatable to Israel. One such concerned the status of the early warning stations in Sinai. Rabin had insisted that in the event of a withdrawal these would remain under Israeli control. Sadat had strongly objected. Now, pondering the matter afresh, the Egyptian president suggested that perhaps they could be manned by American personnel. Kissinger immediately seized upon the idea and adroitly renovated it, as only he knew how, into a dazzling exercise in diplomatic flattery:

Kissinger:

Again, President Sadat, you reveal yourself as a statesman. I think we can sell this idea. If the Israelis think about it carefully, the idea of Americans manning the warning stations is an interesting one. It is very novel. From the Israeli point of view an American presence is better than an agreement of limited duration. The idea of Americans manning the warning stations engages the United States in a permanent way. It is a better assurance for Israel.

Ford:

I believe it is very saleable to the American public. Moreover, if Israel accepts the proposal, the Israeli supporters [in Congress] would help.

Kissinger (to Ford):

It is very important that this should not be told to Rabin next week [when he was due again in Washington].

(To Sadat):

We will indicate to Rabin that you will be willing to look at the question of the early warning stations, without going into details. And then two weeks after Rabin goes home we will get back to him specifically with your creative idea.

Sadat (to Ford):

You have said that it is saleable in America?

Kissinger (to Sadat):

It is important that you not look too eager for an interim agreement. Say you are going back to Cairo to think about it. If we get tough with Rabin we have a chance of pulling this off.

(To Ford):

You will first have to shake up Rabin, and then you could send me out to the area again.

Sadat:

You mean to present it as an American proposal? You could then adopt the posture of putting pressure on me to accept it. You could say that you insist I modify my position.

Kissinger:

This would enable us to say that President Ford was the one to have broken the impasse.

Sadat (to Egyptian Foreign Minister Fahmi):

Work out the language with Henry.

Fahmi:

This will bring about a major crisis between Egypt and the Soviets.

Sadat (to the Americans):

You have nothing to fear from the Soviets. The Soviets are clumsy and suspicious. The United States will have the upper hand.

Kisisnger:

They cannot do anything.

Ford:

I believe President Sadat’s ideas are saleable.

Kissinger:

To sum up

–

I believe our approach here ought to be that you [Sadat] are going home to consider what each of us has said and weigh our conversation. You should not appear too anxious to get an interim agreement. Say that the prospects are fifty-fifty. We can tell the press that the atmosphere of our talks here was excellent and that both President Ford and President Sadat are going back home to think about the substance of our conversations.

Sadat:

And at the appropriate time I will bear witness that it was President Ford who was responsible for finally breaking the impasse and achieving an interim agreement.

42

Thus it was that after more comings and goings, triggering recriminations and vindications, initial tentative understandings began to emerge until, finally, the obstacles to a Sinai interim agreement, which came to be known as Sinai

ii

, began to melt away, one by one. As scripted in Salzburg, President Sadat wobbled about the desirability of such a settlement at all, saying its prospects were at best “fifty-fifty.” President Ford promptly “pressured” him into a rethink, and proposed an American presence in Sinai. Rabin agreed, as did the Egyptian leader, after much questioning and hesitation. Sadat then applauded the American president for having finally broken the impasse, and Secretary of State Kissinger flew out once more to the Middle East to wrap up the whole thing.

The Israeli line at the eastern end of the Sinai passes

–

the Gidi and the Mitla

–

was finally settled, an American presence in the early warning stations (the Sinai Support Mission) was put into place, the Sinai oilfields were transferred back to Egypt, and, with that, the agreement was ready for signing.

Needless to say, President Ford was delighted at the successful outcome of his and Kissinger’s efforts and on the day of the signing, 1 September 1975, he telephoned Rabin in Jerusalem to express his congratulations. Tasked with transcribing the exchange, I hardly recorded a word of it because it turned out to be a four-minute swap of unexceptional platitudes. Not so in the case of the call the president made to Anwar Sadat in Alexandria on the same day.