The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership (76 page)

Read The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership Online

Authors: Yehuda Avner

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #Politics

“What’s up?” I asked.

“Where have you been?”

“With friends over Shabbat. Why? Anything wrong?”

“I’m waiting for Dr. Gotsman. I need him urgently.”

Dr. Mervyn Gotsman habitually accompanied Begin on his travels overseas.

“What’s wrong? I asked.

“Aliza’s dead!”

An icicle of horror and sadness trickled down my spine. Distraught though Yechiel was, he remained admirably contained as he explained how the prime minister’s son, Benny, had phoned him from Jerusalem with the heartbreaking news. Yechiel’s first act was to try and track down Dr. Gotsman on his beeper, but he didn’t answer. He needed him by his side when conveying the bitter news to Begin, and to his daughter, Leah, who had accompanied him on this trip.

“Presumably we’ll be turning around and flying straight home tonight,” I ventured.

“Yes. I’ve already instructed the crew to ready the plane for departure at nine. Meanwhile, don’t tell a soul.”

By the time Dr. Gotsman turned up, it was twilight. He’d gone to synagogue for the afternoon

service and had been in the process of reciting the blessing over the Torah when his beeper went off. He promptly phoned the Israeli duty officer on the hotel’s nineteenth floor, where the prime minister’s suite was located, but she had no idea what it was about. So he hurried back, and, given the news, grabbed his medical bag and went off with Yechiel and Hart and Simona Hasten, old friends of the Begins, to the prime minister’s suite. Filing silently inside they found Begin sitting on a sofa reading a book, splendidly attired in his tuxedo, in readiness for the evening’s banquet.

“What’s happened?” he asked, looking up, his face suddenly waxen.

“Alla has gone,” said Yechiel in a hushed and sorrowful tone.

Anguish overcame him and tears began welling up in his eyes.

“

Lama azavti otta?

” [Why did I leave her], he wailed, shaking back and forth in grief. Over and over again he cried this lament, refusing all consolation.

Yechiel went in search of the prime minister’s daughter, Leah. When he escorted her back into the room she took one look at her father, and cried, “Ima! It’s Ima! What’s happened to my mother?” Told of her passing, she slumped into the embrace of Simona Hasten, who gently lowered her onto the couch where she leaned against her father, sobbing.

Yechiel described this to me when he left the room, and told me to inform Sam Rothberg of our imminent departure. I found Sam at the end of the corridor, looking drained of all color. He already knew; Hart Hasten had told him. They had bumped into one another as Sam was on his way to the prime minister’s suite for a relaxed chat prior to escorting him to the grand ballroom for the gala affair.

An hour or so later, with an ashen face and haunted eyes, Menachem Begin shambled onto the plane and allowed Yechiel to settle him in the aircraft’s tiny sleeping cabin, from which he hardly emerged throughout the tedious sixteen-hour flight back to Tel Aviv. When we landed briefly in New York for refueling, the traveling journalists rushed to the telephone booths to phone in their pieces. Taking advantage of the stopover to stretch my legs, I caught snippets of what they were dictating into the receivers; all seemed to be saying much the same thing:

“It was a simple, old-fashioned, lifelong love affair…”

“The prime minister relied on her totally…”

“She was the only person he really confided in…”

“She managed all his personal affairs…”

“Only with her was he absolutely candid and open…”

“Begin needed three things above all

–

devotion, tranquility, and companionship, and she gave him all three…”

Over the Atlantic, I asked Yechiel where Mrs. Begin was to be buried, and he answered that he had broached the matter gingerly with the prime minister, prior to leaving Los Angeles.

“I didn’t want to use the word bury,” he said. “I thought it too awful. So I said funeral. ‘Menachem,’ I said, ‘where do you want Alla’s funeral to be?’ He said, ‘The same place as for me.’ So I said, ‘But I don’t know where that is.’ He said, ‘You have it in my will. I gave it to you a long time ago in a sealed envelope.’ I said I had the envelope, but I’d never opened it because it was my understanding I was to open it only after he’d gone. He seemed to assume he’d go first. He understood the predicament and said, ‘I want the funeral to be on the Mount of Olives, as near as possible to Moshe Barazani and Meir Feinstein. That’s what’s written in the envelope.’”

Moshe Barazani and Meir Feinstein had been two heroes of Menachem Begin’s underground days. Condemned to death, they resolved that rather than swing on a rope tied by a British executioner, they would take their own lives, and this they did by embracing each other and blowing themselves up with an improvised hand grenade lodged between them.

Aliza Begin, sixty-two, was laid to rest on the Mount of Olives alongside these martyrs, and Yechiel made sure that the adjacent plot was reserved for Menachem Begin.

During the

shiva

week, the seven days of ritual mourning following the funeral, when the bereaved sit on low chairs, wear ripped garments and male mourners go unshaven, the prime minister received all comers in what was an extraordinary display of shared grief. People lined up in droves to convey their condolences, people from every walk of life: shopkeepers, professors, politicians, yeshiva students, entrepreneurs, soldiers, rabbis, diplomats, housewives; even men and women who had served jail sentences, and former drug addicts and prostitutes whom Aliza Begin had discreetly helped rehabilitate. Her husband knew absolutely nothing about this until they told him.

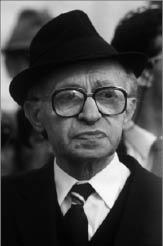

At Aliza’s graveside, November 1982

Photograph credit: Yitzhak Harari

As we have seen, Begin revered religious Jews who spent their time immersed in rabbinical texts, and he had a particular admiration for the scholarship of his colleague Dr. Yosef Burg, who was a prewar graduate of the famed Berlin Hildesheimer Rabbinical Seminary and of the Berlin University. His erudition was amply displayed when he was gave the eulogy for the deceased during the

shiva

.

“The Kabbalah tells us,” Dr. Burg began, “that there is a Torah that cannot be memorized or written down. It is a Torah not of study or of learning, not of intellect or of scholarship, not of innovation or of disputation. It is a Torah without words

.

It is a Torah of the

nefes

h

, of the soul, and it is the sweetest Torah of all.

“Nothing we say or write, could ever do justice to, or truly fathom, the

nefesh

of Aliza Begin

–

the warmth and love that flowed from her inner being, the demands she made of herself day by day, her sacrifices in the underground for the sake of Eretz Yisrael, her work for the needy and for the sick, for those ailing in body and in spirit; her courage, her vigor, her faith, her fortitude; her love and laughter, her readiness to spare nothing of herself for the sake of her children and her husband. Only when we come together, as we do now at this

shiva

, and talk of her virtues, can we share a little something of the nobility and stature of the

nefesh

of Aliza Begin.

“In Judaism, memory is everything. No less than one hundred and sixty-nine times does the Torah command us to remember the past. The significance of memory is that, by it, the past is made part of the present. If you erase the power of memory you shatter the sense of time. Time is past, present and future. And the existence of a future in Judaism is

netzach

–

eternity. To the bereaved the future is also a

ma’aseh chesed

–

a divine act of loving kindness. It is a

ma’aseh chesed

because even as one remembers the passing of a loved one, the future is a promise that the agony of grief will, in time, mellow.

“In Judaism there are two kinds of memory:

zikaron

and

yizko

r

.

Zikaron

is ephemeral; it fades.

Yizkor

is eternal. If one loses a distant friend, one has pangs of memory and a sense of a place that he or she once filled. The most dismaying thing about such a death is not the gap that it leaves, but how the memory of it becomes a mere echo of the past. That is

zikaron

.

“However, there is that other quality of memory that never dims. It never dims because the person we recollect is a part of oneself:

‘

basar m’basarcha, nefesh m’nafshecha’ [flesh of your flesh, soul of your soul].The deceased remains a living being within one’s soul forever. And that is yizkor.

“And in

yizkor

we acknowledge that the finality of death is part of life. Or, in the words of Ecclesiastes, ‘To everything there is a season: A time to be born, and a time to die.’ Often, we see the Almighty plucking a beautiful life just when, to us, he or she appears in full blossom. And then we ask,

lama

? Why? The prophet Isaiah gives the answer. His answer is that the thoughts of the Almighty are beyond the capacity of mortal minds. And so we are confused and frightened, and ask questions to which there are no answers, except for the one in Deuteronomy, chapter thirty-two, verse four:

‘

Hatzur tamim po’alo, ki kol devarav mishpat

’ [The Rock, the Almighty, His work is perfect, for all His ways are justice].

“This means that in Judaism there is no such thing as an irrational

,

meaningless fate

.

In the words of the eminent rabbinic scholar, Rabbi Yosef Ber Soloveitchik, Judaism rejects the notion of random events in life. Judaism rejects any belief in a determinate luck or in a blind fate

.

We do not believe in fate as did the Greeks, who saw everything affected by absurd, unalterable, and ruthless decrees which emanated from some remote unknown. Such a belief crushes a man’s dreams, irrespective of what he does or does not do. This, to the Greeks, was the source of human tragedy. Man becomes a helpless pawn in the hands of inexorable forces which cannot be thwarted, even by the gods.’”

Here, Dr. Burg paused, and looking directly at the prime minister, his son Benny, and his daughters, Hassya and Leah, who were sitting low by their father’s side, he ended, “Even as Judaism tries to comprehend catastrophic events which cruelly destroy man’s dreams, Judaism cannot accept the existence of the ultimately irrational in human life. Events which we label as tragic belong to a higher divine order into which man has not been initiated. The world is governed not by decrees of fate but by reasons beyond our comprehension. We have been granted insights into the physical nature of life through the accumulation of scientific knowledge, but we are excluded from the realm of

divine understanding. The relationship between the individual and what becomes of him or her eludes our grasp. Thus it is that even as we mourn the passing of your beloved wife and mother, Aliza, we acknowledge that to God there are no arbitrary happenings. This is why upon hearing of her passing we declared,

‘

Baruch Dayan ha’emet!

’ [Blessed be the Judge of the truth]. And this is why we affirmed at her graveside,

‘

Hashem natan, Hashem lakach, yehi shem Hashem l’olam va’ed

,’ [The Lord has given, the Lord has taken away, blessed be the name of the Lord forever]. And blessed shall be the remembrance of Aliza Begin forever.”

The prime minister, his face worn, his skin as gray as the leaden November sky outside, rose to shake Yosef Burg’s hand, but Burg restrained him, saying, “It is not customary in a house of mourning for the bereaved to express thanks.”

“Nevertheless, you have my gratitude,” said Begin. “Your words are a great comfort.”

“Time for

ma’ari

v

,” somebody cried out, and as befitted the son of the deceased, Benny Begin led the prayers of the evening service. To the uninitiated, of which there were many that night, the words of the congregants must have sounded like a Babel of mutterings and chantings, punctuated every now and again by a loud

“

Oomeyn

” [Amen]. At one point, the chattering of the non-congregants grew so loud it elicited a reproachful “Sh-sh-sh!” from the congregants. However, all stood in solemn silence as Benny Begin rounded off the service by reciting the mourner’s

Kaddish

, which opens with a vision of God becoming great in the eyes of all nations, and ends with a supplication for peace, to which all chorused “Amen!”

When she heard that Aliza Begin had died, Mrs. Jehan Sadat, widow of the slain President Anwar Sadat, picked up the phone in her Cairo home, with its spectacular view of the Nile, and placed a call to Israel’s ambassador to Egypt, Moshe Sasson. She invited him for coffee, and Sasson, a man with vast experience in Arab affairs assumed, correctly, that the former first lady of Egypt wished to speak to him privately.

Though more than a year had passed since her husband’s assassination, Jehan Sadat remained a highly popular figure among influential circles in Egyptian society, thanks to her sharp mind, her stunning beauty, and her continuing outspoken and courageous activism on behalf of Egyptian women. Given the autocratic nature of Arab society, and the fact that Jehan Sadat’s image far outshone that of Mrs. Mubarak, it was certainly possible that President Hosni Mubarak was keeping a watchful eye on her comings and goings.

“I have a letter of condolence for your prime minister,” said Jehan, upon receiving Ambassador Sasson. “I would appreciate it if you could communicate it as soon as possible.” She handed him an envelope.

“Of course,” said Sasson, pocketing it.

“Coffee?” asked Mrs. Sadat, as a maid walked in.

“Please.”