The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership (74 page)

Read The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership Online

Authors: Yehuda Avner

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #Politics

“I understand,” said Lewis

–

he really did

–

“but I am required to tell you that the president intends to make his plan public within the next seventy-two hours.”

“In that case I ask you to please ask the president, on my behalf, to defer his speech for five or six days so as to enable me to return to Jerusalem to convene the cabinet for a full debate.”

“I will certainly report your request, Mr. Prime Minister, but I have no way of knowing if the president can wait that long. He is very sensitive to premature leaks.”

With weary dignity and a voice full of entreaty, Begin said, “Sam, this plan has been thrust upon us. It bears upon our very existence. I think President Reagan owes me at least that much; to give my government time to render a considered response.”

“I promise I will do my very best,” said the ambassador, rising and slipping his notebook into his briefcase. “I’ve made a record of everything you’ve said, and I shall now dash back to Tel Aviv and cable off your reaction and your request. And again, forgive me. I regret I had to interrupt your holiday for this purpose.”

“So do I, Sam. So do I,” muttered an unhappy prime minister.

The next evening, while the ambassador was attending a cocktail reception, one of his staff members nudged his way through the cluster of guests to deliver an urgent and highly classified cable which had just reached the embassy. When Lewis read it in the privacy of an out-of-the-way hallway, his left eyebrow rose a fraction, his heart missed a beat, and he muttered a sigh of dismay. His instruction was to deliver this message to the prime minister without delay, before the cabinet had time to formulate its response, which was set for the following morning. He pondered what best to do – drive straight to Nahariya and deliver the message personally, or take the inevitable flack over the telephone? He looked at his watch. It was late – too late to drive to Nahariya, so he sought out his chauffeur and told him to take him back to his embassy. “I have a call to make,” he said, and on his way over, he pondered how best to make it.

“Good evening, Mrs. Begin. Forgive me for disturbing you again. It’s Sam Lewis. May I

–

”

“Hold on. My husband is right here. Menachem, pick up the extension. It’s Mr. Lewis.”

“Hello, Sam. You have news?”

“I do, Mr. Prime Minister, and I’m afraid it’s not as good as I would have wished.”

Silence.

“Mr. Prime Minister, are you there?”

“Oh, yes, Mr. Ambassador, I am here, waiting to hear what you have to tell me.” There was a spike of reproach in his voice.

Lewis spoke in as reasonable a tone as he could manage. “My instructions are to tell you that the president is unable to postpone his public address as you requested.”

“Unable to postpone? Why not?” Begin’s bitterness spilled through the receiver.

“Because some of its substance has already been leaked and, therefore, the president has decided to deliver his speech this evening, Washington time.”

“This evening?! The president is making his initiative public this evening

–

even before my cabinet has the opportunity to deliberate upon it tomorrow morning?”

“I’m, afraid so, Mr. Prime Minister. I’m sorry.”

“As well you might be, Mr. Ambassador.”

The outrage in Begin’s voice was peppered with a bitter cynicism. “Is this the way to treat a friend? Is this the way to treat an ally? Your government consorts with our despotic enemies and yet you choose to ignore us on a matter of vital import to our future? What kind of a discourse is this between democratic peoples who purport to cherish common values? Is this the way to make peace? We do not deserve this kind of treatment.” And then, in a voice that had hardened ruthlessly: “Mr. Ambassador, please convey to the president exactly what I’ve just said. Tell him I am hurt to the core. And tell him that our cabinet will convene tomorrow as planned, and then we shall provide your government with our official response. Good night!”96

The response came in the form of a meticulously detailed and comprehensive refutation of every single point of the president’s plan. The penultimate paragraph read, “Since the positions of the government of the United States seriously deviate from the Camp David agreements, contradict it, and could create a serious danger to Israel, its security and future, the government of Israel has resolved that on the basis of these positions it will not enter into any negotiations with any party.”

97

That done, the prime minister called me in to request I go over the draft of his accompanying letter to the president, which he had composed on paper from the boarding house before leaving Nahariya. After some minor ‘shakespearizations’ this is how it read:

Dear Ron,

Thank you for your letter of 31 August, 1982, which Ambassador Lewis was kind enough, upon instructions from his government, to bring to me to Nahariya, now free of rockets and shells.

I enclose, herewith, the resolution of the cabinet, September 2, 1982, adopted unanimously. As each of the paragraphs is elaborated, I have little to add except to state

–

taking if I may a leaf from your book

–

that the government of Israel will stand by the decision with total dedication.

I have also read your speech, which preceded by twenty-four hours the cabinet consultation with my colleagues. It serves as additional testimony to your opinion or resolve. Indeed, my friend, great events did take place since we last met in Washington in June. May I, however, give you a somewhat different version of those events? On 6 June, the Israeli Defense Forces entered Lebanon in order not to conquer territory, but to fight and smash the armed bands operating from that country against our land and its citizens. This, the

IDF

did. You will recall that we could not, regrettably, accept your suggestion that we proclaim a ceasefire on Thursday, 10 June, at 06:00 hours, because at that time the enemy was still eighteen kilometers from Metula, on our northern border. However, twenty-four hours later we pushed the enemy further northwards and we proclaimed a unilateral ceasefire on Friday 11 June at 12 noon. This was rejected by the terrorists. So the fighting continued, and it went on until 21 June when we suggested that all the terrorists leave Beirut and Lebanon, which they did with the help of the important good offices of Ambassador Philip Habib many weeks later. In the ensuing battles Israel lost 340 men killed and 2,200 wounded, 100 of them severely.

When the Syrian Army entered the fray

–

against all our appeals

–

we destroyed 405 Soviet-Syrian tanks, downed 102 Soviet-Syrian

MIG

s (including one

MIG

-25) and smashed 21 batteries of

SAM

-6,

SAM

-8, and

SAM

-9 air-to-ground missiles

–

all deadly weapons. Yet, in your letter to me, as in your speech to the American people, you didn’t, Mr. President, see fit to mention even once the bravery of the Israeli fighter, and the great sacrifices of the Israeli army and our people. The impression one could have gotten was that Ambassador Philip Habib, with the help of expeditionary units, achieved this result. It is my duty to tell you, Mr. President, that I was struck by this omission. I state a fact. I do not complain.

What I do protest against is the omission to consult with us prior to sending out your proposals to Jordan and Saudi Arabia, the former an outspoken opponent of the Camp David Accords, the latter a complete stranger to, and an adversary of, those accords.

In face of the fact that there was no prior consultation, the U.S. government adopted the position that the ‘West Bank’ be re-associated with Jordan. What some call the ‘West Bank,’ Mr. President, is Judea and Samaria, and this simple historic truth will never change. There are cynics who mock history. They may deride history as much as they wish. I stand by the truth

–

the truth that millennia ago there was a Jewish kingdom of Judea and Samaria, where our kings knelt to God, where our prophets brought forth the vision of eternal peace, where we developed our rich civilization which we took with us in our hearts and minds on our long global trek for over eighteen centuries and, with it, we came back home.

By aggressive war and by invasion, King Abdullah [of Jordan] conquered parts of Samaria and Judea in 1948. Subsequently, in a war of most legitimate self-defense in 1967, after having been attacked by King Hussein [of Jordan], we liberated, with the Almighty’s help, that same region of our homeland.

Judea and Samaria will never again be the ‘West Bank’ of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, created by British colonialism after the French Army expelled King Faisel from Damascus [at the end of World War One].

At Camp David we suggested

–

yes, it was our initiative

–

full autonomy for the Arabs of Palestine, inhabitants of Judea and Samaria and the Gaza district, with a transitional period of five years. It is a generous suggestion of the widest scope of autonomy existing on earth in our time….

Geography and history have determined that the matter of security remains paramount, for Judea and Samaria are mountainous country; two-thirds of our population lives in the coastal plain below. From those mountains you can hit every city, every town, each township and village, and last but not least, our principal airport [Ben-Gurion] in the plain below. We used to live penned up in eight miles from the seashore and now, Mr. President, you suggest to us in your proposals that we return to almost that same situation.

True, you declare you will not support the creation of a Palestinian state in Judea, Samaria, and the Gaza district. But such a state will arise of itself the day Judea and Samaria are given to Jordanian jurisdiction. Then, in no time, we and you will have a Soviet base in the heart of the Middle East. Under no circumstances shall we accept such a possibility ever arising, which would endanger our very existence.

Mr. President, you and I chose for the last two years to call our countries ‘friends and allies.’ Such being the case, a friend does not weaken his friend, and an ally does not put his ally in jeopardy. This would be the inevitable consequence were the ‘positions’ transmitted to me on August 31, 1982, to become reality.

I believe they won’t.

‘

L’ma’an Zion lo echeshe, u’l’ma’an Yerushalayim lo eshkot

’

–

For Zion’s sake I will not hold my peace, and for Jerusalem’s sake I will not rest. (Isaiah, chapter 62).

Yours respectfully and sincerely,

Menachem

98

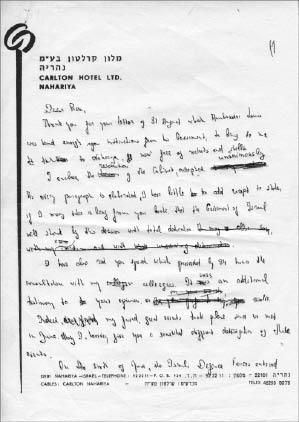

First page of Prime Minister Begin's draft letter to President Reagan, categorically rejecting his peace plan, 2 September 1982

The Rosh Hashanah of Sabra and Shatila

The ambitious Reagan initiative was so flawed it was doomed to failure before it even got off the ground. Moreover, it was swiftly overtaken by events, when yet another ghastly calamity rocked Lebanon. On 14 September 1982, that country’s president-elect, Bashir Gemayel, on whom Begin had pinned his hopes for peace, was assassinated. In revenge, Christian militias slaughtered hundreds of Muslim civilians in two Palestinian refugee camps in West Beirut, known as Sabra and Shatila. This horrendous massacre occurred on the eve of Rosh Hashanah, 16 September. On the following morning, Mr. Begin stood waiting for me in the hallway of his residence, where I was meeting him to escort him to synagogue. His face was like stone. Contemptuously he snapped,

“

Host du gehert aza meisa?

[Have you heard of such a thing?] Christians massacre Muslims and the goyim blame the Jews.”

Dumbfounded, I said, “I don’t understand.”

“Precisely what I’m telling you. I first heard it on the

BBC

. I checked with our commanders on the spot. They told me it was true. Christian militias entered two Palestinian refugee camps in West Beirut to flush out residual

PLO

terrorist nests, and then set upon civilians, massacring hundreds. Our own men put a stop to it, yet predictably, the foreign media are blaming us.” He looked at his watch. “Come, let us go. I’ll tell you about it on the way.”

Still not totally recovered from his broken hip, the prime minister grasped his cane, handed me the velvet pouch containing his prayer shawl, gripped my arm for support and, surrounded by bodyguards, began limping the few blocks toward Jerusalem’s Great Synagogue, pausing periodically to acknowledge the New Year greetings of respectful passersby. While he walked, he leaned heavily on my arm and recounted what he knew of the hideous events that had occurred in Beirut over the past several days.

According to reports, buildings filled with people had been dynamited to the ground. The alleyways in the two refugee camps were filled with entangled corpses, hastily dug mass graves, and bodies bulldozed to the sides of lanes. Lebanon was slowly bleeding to death in the abattoir of its civil war, which had been ravaging its people since 1975. And even though everyone knew that in years past, Lebanese Arab Muslims and Lebanese Arab Christians had inflicted far more terrible slaughters on each other, and even though everyone knew that no Israelis were directly involved in these latest massacres, the Jewish State had been put in the dock of public opinion for allegedly having allowed the slaughter to happen.

“There’s no one more respectful of world opinion than me,” said Begin, with a hint of sarcasm, as we approached the synagogue. “But when papers in Washington, London and Paris brand us as aggressors and don’t have a single accusatory word to say about those trying to kill our innocents, then we have to conclude that we face a blatant media bias.”

“In other words, anti-Semitism,” I said.

He paused, looked at me morosely, and said what he really meant: “There are many bleeding hearts among the goyim who say, ‘God forbid

–

us, anti-Semites? Never! We’re just anti-Israel.’ Believe me, there comes a point where it’s impossible to distinguish one from the other. This is why we have to stand up to these people and never be apologetic. We have to constantly remind them how their papers didn’t say a single word while six million of our brethren were being slaughtered. Never once did they make an effort to pressure their governments to come to the rescue of even a single Jewish child. So I’m not at all surprised at this innate bias. It’s always been the same”

–

this with a snarl

–

“goyim kill goyim and they hang the Jews.”

This was not the only source of grief for the prime minister on that Rosh Hashanah. He deeply lamented the demise of the prospect of another treaty of peace with a neighbor. President-elect Bashir Gemayel had been so well disposed toward Israel that he had begun to deliberate seriously about being the next signatory to a treaty. Indeed, the prime minister, along with his defense minister Ariel Sharon, had been intensely engaged with Gemayel, negotiating its details. But just as the young president-elect was about to be officially inaugurated and assume formal control of his fractious domain, he was murdered, and the fragments of the peace treaty draft were left scattered among his remains.

And there was something else besides that distressed the prime minister as we walked to the Jerusalem Great Synagogue that day. Although the Peace for Galilee campaign had ended to his satisfaction, the fact that Israeli troops were still engaged deep inside Lebanon, with mounting casualties, had caused ever-increasing numbers of the public to regard the war without conviction. Angry and frustrated by the souring of events – what was originally conceived as a brief campaign had stretched from June into July, August, and now September – Israel was enduring protests and demonstrations almost daily. One group of antiwar protestors had mounted an around-the-clock vigil directly in front of the prime minister’s residence, with a huge placard displaying the rising toll of the fallen, which, by that Rosh Hashanah, totaled more than six hundred. Whenever the newest casualty figures were brought to Begin’s attention we, his staff, had marked his deep sorrow. His heart broke silently and a dull throb of grief possessed his spirit. “It’s as though I do not have a home anymore,” he told Dr. Burg wearily, speaking of the demonstrators outside his house. “It’s as though I’m living on the street.”

“I shall have them removed,” declared Burg, who possessed the ministerial authority to do so.

“Under no circumstances,” said Begin.

“But they are such a disturbance to you. In no other country are demonstrators allowed to demonstrate right in front of a prime minister’s house.”

“It is their democratic right,” Begin had insisted. “Let them stay. I only pray they don’t disturb the neighbors too much.”

It was perhaps natural that Begin should accuse the leader of the Labor opposition, Shimon Peres, for the deepening civic rift. He had charged him with being more interested in pulling down national

pillars

than pondering the rights and wrongs of the war, the first in which partisan political divisions were ripping the country apart.

The man Peres wanted to bring down most, as, indeed, did some of Mr. Begin’s own cabinet, was Defense Minister Sharon. To his antagonists, Sharon’s purposes were as clear as that of a fox in a hen coop. The warrior who had long earned a reputation for boldness, decisiveness, and tactical skill was now being depicted as a satanic militarist. The Labor opposition had fingered him for every foul-up, and now they were demanding he be dismissed or be made to resign for mishandling the war and for allowing the Christian militia to enter Sabra and Shatila, even though he could not have possibly foreseen the terrible consequences.

“There will be no resignations and no dismissals,” said the prime minister as we mounted the steps to the sanctuary. Once inside, he immediately calmed down, as if surrendering to the embrace of its sanctity. Wrapped in his prayer shawl, he worshipped with quiet passion, reading from a tattered prayer book that had been given to him as a bar mitzvah gift, pronouncing the words in the soft Ashkenazi intonations of his Warsaw youth. And when the cantor and the choir reached the pinnacle of the service in chanting the mournful prayer, “U’Netaneh Tokef Kedushat Hayom” [Let us tell how utterly holy is this day for it is awesome and terrible], his eyes glistened, and he swayed back and forth in profound piety.

Slowly and sorrowfully, the cantor came to the wrenching and brokenhearted incantation, “On Rosh Hashanah it is inscribed, and on Yom Kippur it is sealed: How many shall pass away, and how many shall be born. Who shall live and who shall die.” Sighs and sobs swelled from the throats of the Jews in those pews where Menachem Begin stood, as the cantor’s voice swelled in an agony of reverence, his eyes closed, his body swaying, his hands stretched out and up: “Who shall perish by the sword and who by wild beast, who by famine and who by thirst…who shall be at peace and who shall be pursued. Who shall be at rest and who tormented. Who shall be exalted and who shall be brought low. Who shall prosper and who shall be impoverished.”

In answer to the suspended verdict of this dirge, the cantor rose on his toes in a finale of trembling and exulted conviction, and cried out at the top of his voice, in thunderous unison with the entire congregation, many of whom had endured the torment of the Holocaust and the bereavement of Israel’s wars,

“

U’teshuvah u’tefillah u’tzedakah ma’avirin et ro’a ha’gzeirah

” [But repentance, prayer and charity shall avert the severe decree].

Whereupon, I felt a gentle tap on my shoulder as if from on High, but it was only Zabush, chief of the prime minister’s security detail that day.

“There’s an ugly demonstration building up outside,” he whispered into my ear. “You will have to take the prime minister out through the rear exit. We’ll cut through the back alleyway and across the street to his home.”

I transmitted this discreetly to Mr. Begin, behind whom I was sitting, but he gave no sign of acknowledgement. He was bent over his prayer book, steeped in the cantorial renditions and the congregational recitations, mouthing each supplication with the fervor of a believer. Upon the service’s culmination, in buoyant optimism that prayers will indeed be answered, multitudes of congregants swarmed around him to wish him a

Shanah Tovah

–

a happy new year.

Beaming, he shook every hand, and when he finally took my arm to go, Zabush hissed, “Follow me.” I did, leading the prime minister through the last remaining clusters of well-wishing congregants, and toward the synagogue’s rear exit.

“Where are you taking me?” demanded Begin, halting mid-stride.

Zabush explained.

“Under no circumstances will I go out this way,” he retorted angrily. “I will not slink out of the synagogue. I will leave the way I came, through the front door, demonstration or no demonstration.”

Zabush spoke into his walkie-talkie urgently, alerting his squad outside. As the prime minister emerged into the synagogue’s forecourt, a horde of demonstrators tried to crush in upon him. Spittle, clenched fists, and cries of “Murderer!” assaulted the sanctity of the day as anxious policemen and guards pushed, kicked, and elbowed the baying crowd, cutting a channel through the crush to form a close cordon around us, while swarms of reporters recorded the pandemonium.

The prime minister’s bespectacled, bony features showed nothing but boldness, but rage was swelling within him. I could feel it in the sharp nip of his fingers pinching into my arm as he leaned on me. He was deliberately limping at an artificially slow pace in a show of defiance that made my every nerve shudder.

All the frustrations over the long Lebanese war seemed to explode on that Rosh Hashanah outside the Great Synagogue, as protestors yelled over and over again, “Begin is a murderer!” Some surged ahead to join the pickets encamped across the street from the prime minister’s home, and as Begin advanced toward it at a snail’s pace, encircled by ring upon ring of policemen and bodyguards, he leaned so hard against me that my arm went numb. Once safely inside, the protesters yelled at him to come outside again. “Come outside, man of blood,” they roared. “Come outside, killer of Sabra and Shatila!”

I left Menachem Begin to limp upstairs alone to his private

quarters

and his ailing wife, whereupon I beat a quick retreat through a side door to join my family, who had all the while been witness to this Rosh Hashanah horror.

Predictably, the demonstrators clamored for an official commission of inquiry to pass judgment as to what had truly happened at Sabra and Shatila. Thus was the Kahan Commission born, named after its chairman, the president of the Supreme Court, Yitzhak Kahan. It was composed of persons of high repute who subjected those appearing before them, the prime minister included, to a most exhaustive, though always polite, cross examination.

The commission issued its report in February, 1983, and concluded that Ariel Sharon, as minister of defense, carried an “indirect responsibility” for the atrocity at Sabra and Shatila by allowing the Christian Phalangists to enter the camps. At that point, it was up to the government to decide what to do

–

to reject the Commission’s findings in whole or in part, or to accept them. The cabinet sat for three consecutive sessions to determine its position, while Ariel Sharon waited impatiently through a parade of interminable monologues, as each minister was invited to speak his piece. When the vote finally came, it was sixteen to one in favor of adopting the commission’s findings in their entirety.

With his marvelous incapacity to admit error, Sharon utterly rejected this stigmatization. Controversy raged for years after, between critics and partisans alike, over the Kahan Commission findings, and Sharon’s guilt or innocence, and over the true nature of Menachem Begin’s feelings toward him. What is undisputable is that Begin accepted Sharon’s resignation as defense minister, although he did retain him in the cabinet, as a minister without portfolio.

However harsh the self-examination to which Israel subjected itself in probing the facts of Sabra and Shatila, nothing seemed to help in stemming the tide of overseas criticism and condemnation, even from some of the Jewish State’s staunchest supporters. One such was Senator Alan Cranston who, days after the massacre, issued a public letter addressed to Prime Minister Begin in which he wrote, inter alia: