The Professor and the Madman: A Tale of Murder, Insanity, and the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary (10 page)

Authors: Simon Winchester

Tags: #General, #United States, #Biography, #Biography & Autobiography, #Psychiatric Hospital Patients, #Great Britain, #English Language, #English Language - Etymology, #Encyclopedias and Dictionaries - History and Criticism, #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865 - Veterans, #Lexicographers - Great Britain, #Minor; William Chester, #Murray; James Augustus Henry - Friends and Associates, #Lexicographers, #History and Criticism, #Encyclopedias and Dictionaries, #English Language - Lexicography, #Psychiatric Hospital Patients - Great Britain, #New English Dictionary on Historical Principles, #Oxford English Dictionary

The rest—and most first-time offenders—were usually subjected to public humiliations of varying kinds. Some had their heads shaved or half shaved, and were forced to wear boards with the inscription “Coward.” Some were sentenced by drumhead courts-martial to a painful ordeal called “bucking,” in which the wrists were tied tightly, the arms forced over the knees, and a stick secured beneath knees and arms—leaving the convict in an excruciating contortion, often for days at a time. (It was a punishment so harsh as to prove often decidedly counterproductive: One general who ordered a man to be bucked for straggling found that half his company deserted in protest.)

A man could also be gagged with a bayonet, which was tied across his open mouth with twine. He could be suspended from his thumbs, made to carry a yard of rail across his shoulders, be drummed out of town, forced to ride a wooden horse, made to walk around in a barrel shirt and no other clothes—he could even, as in one gruesome case in Tennessee, be nailed to a tree, crucified.

Or else—and here it seemed was the perfect combination of pain and humiliation—he could be branded. The letter

D

would be seared onto his buttock, his hip, or his cheek. It would be a letter one and a half inches high—the regulations became quite specific on this point—and it would either be burned on with a hot iron or cut with a razor and the wound filled with black powder, both to cause irritation and indelibility.

For some unknown reason the regimental drummer boy would often be employed to administer the powder; or in the case of the use of a branding iron, the doctor. And this, it was said at the London trial, was what William Minor had been forced to do.

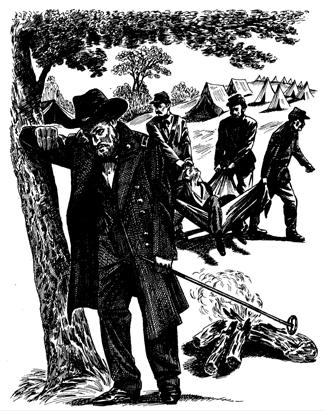

An Irish deserter, who had been convicted at drumhead of running away during the terrors of the Wilderness, was sentenced to be branded. The officers of the court—there would have been a colonel, four captains, and three lieutenants—demanded in this case that the new young acting assistant surgeon who had been assigned to them, this fresh-faced and genteel-looking aristocrat, this Yalie, fresh down from the hills of New England, be instructed to carry out the punishment. It would be as good a way as any, the old war-weary officers implied, to induct Doctor Minor into the rigors of war. And so the Irishman was brought to him, his arms shackled behind his back.

He was a dirty and unkempt man in his early twenties, his dark uniform torn to rags by his frantic, desperate run through the brambles. He was exhausted and frightened. He was like an animal—a far cry from the young lad who had arrived, cocksure and full of Dublin mischief, on the West Side of Manhattan three years earlier. He had seen so much fighting, so much dying—and yet now the cause for which he had fought was no longer truly his cause, not since Emancipation, certainly. His side was winning, anyway—they wouldn’t be needing him anymore, they wouldn’t miss him if he ran away.

He wanted to be rid of his duties for the alien Americans. He wanted to go back home to Ireland. He wanted to see his family again and be finished with this strange foreign conflict to which, in truth, he had never been more than a mercenary party. He wanted to use the soldiering skills he had learned in all those fights in Pennsylvania and Maryland and now in the fields of Virginia, to fight against the despised British, occupiers of his homeland.

But now he had made the mistake of trying to run, and five soldiers from the provost marshal’s unit, on the lookout for him, had grabbed him from where he had been hiding behind the barn on a farm up in the foothills. The court-martial had been assembled all too quickly and, as with all drumhead justice, the sentence was handed down in a brutally short time: He was to be flogged, thirty lashes with the cat—but only after being seared with a branding iron, the mark of desertion forever to scar his face.

He pleaded with the court; he pleaded with his guards. He cried, he screamed, he struggled. But the soldiers held him down, and Doctor Minor took the hot iron from a basket of glowing coals that had been hastily borrowed from the brigade farrier. He hesitated for a moment—a hesitation that betrayed his own reluctance—for was this, he wondered briefly, truly permitted under the terms of his Hippocratic oath? The officers grunted for him to continue—and he pressed the glowing metal onto the Irishman’s cheek. The flesh sizzled, the blood bubbled and steamed; the prisoner screamed and screamed.

And then it was over. The wretch was led away, holding to his injured cheek the alcohol-soaked rag that Minor had given him. Perhaps the wound would become infected, would fill with the “laudable pus” that other doctors said hinted at cure. Perhaps it would fester and crust with sores. Perhaps it would blister and burst and bleed for weeks. He didn’t know.

All that he was sure of was that the brand would be with him for the rest of his life. While in the United States it would mark him as a coward, as shaming a punishment as the court had decreed, back home in Ireland it would mark him as something else altogether: It would mark him as a man who had gone to America to train with the army, and who was now back in Ireland, bent on fighting against the British authorities. He could clearly be identified, from now on, as a member of one of the Irish nationalist rebel groups. Every soldier and policeman in England and Ireland would recognize that, and would either lock him up to keep him off the streets, or would harass and harry him for every moment of his waking life.

His future as an Irish revolutionary was, in other words, over. He cared little for his ruined social standing in the United States; but for his future and now very vulnerable position in Ireland, he had been marked and blighted forever by the fact of one battlefield punishment, and he was bitterly angry. He realized that as an Irish patriot and revolutionary he was useless, unemployable, worthless in all regards.

And in his anger he most probably felt, justly or not, that his ever-more-intense wrath should be directed against the man who had so betrayed his calling as a medical man and had instead, and without objection, marked his face so savagely and incurably. He would have decided that he was and should be bitterly and eternally angry at William Chester Minor.

So he would go home, he vowed, just as soon as this war was over; and once home he would, the moment he stepped off the boat on the docks at Cobh or Dun Laoghaire (or Queenstown or Kingstown, the ports for Cork and Dublin), tell all Irish patriots the following: William Chester Minor, American, was an enemy of all good Fenian fighting men, and revenge should be exacted from him, in good time and in due course.

This, at least, is what Doctor Minor almost certainly thought was in the mind of the man he had branded. Yes, it was later said, he had been terrified by his exposure to the battlefield, and “exposure in the field” was suggested by some doctors as the cause of his ills; one story also had it that he had been present at the execution of a man—a Yale classmate, according to some reports, though none included a time or a place—and that he had been severely affected by what he had seen; but most frequently it was said he was fearful that Irishmen would abuse him shamefully, as he put it, and this was because he had been ordered to inflict so cruel a punishment on one of their number in the United States.

It was a story that was put about in court—Mrs. Fisher, his landlady in Tennison Street, Lambeth, had, according to the official court reports in

The Times

, suggested as much. The story was raised many times over the following decades—when people remembered that he was still locked up in an asylum—to account for his illness; and until 1915, when as an elderly man he gave an interview to a journalist in Washington, D.C., and told quite another story, it remained one of the leading probable causes for his insanity. “He branded an Irishman during the American Civil War,” they used to say. “It drove him mad.”

A week or so later Minor—suffering no apparent short-term effects from his experience—was moved from under the red flag of the advanced field hospital (the red cross symbol was not to be adopted by the United States until the ratification of the Geneva Convention in the late 1860s) and sent to where he had been originally bound, the city of Alexandria.

He arrived there on May 17, and went first to work at L’Overture Hospital, then reserved largely for black and so-called “contraband” patients—escaped Southern slaves. There are records showing that he moved around the Federal hospital system: He worked at Alexandria General Hospital and at the Slough Hospital; there is also a letter from his old military hospital in New Haven, asking that he come back, since his work had been so good.

Demand like this was unusual, since Minor was laboring still at the lowliest rank of the war’s medical personnel, as an acting assistant surgeon. In the course of the conflict 5,500 men were Federally contracted at this rank, and they included some devastating incompetents—specialists in botany and homeopathy, drunks who had failed in private practice, fraudsters who preyed on their patients, men who had never been to medical school at all. Most would vanish from the army once the fighting was over: Few would even dare hope for promotion or a regular commission.

But William Minor did. He seems to have flung himself into his work. Some of his old autopsy reports survive—they display neat handwriting, a confident use of the language, decisive declarations as to the cause of death. Most of the reports are forlorn—a sergeant from the First Michigan Cavalry dying of lung cancer, a common soldier dying of typhoid, another with pneumonia—all too common ailments during the Civil War period, and all treated with the ignorance of the day, with little more than the dual weapons of opium and calomel, painkiller and purgative.

One report is more interesting: It was written in September 1866—two years after the Wilderness battle—and it concerns a recruit, “a stout muscular man” named Martin Kuster, who was struck by lightning while he was on sentry duty, imprudently standing under a poplar tree during a thunderstorm. He was in bad shape. “The left side of his cap open…facing of the metal button torn off…hair of his left temple singed and burned…stocking and right boot torn open…a faint yellow and amber colored line extended down his body…burns down to his pubis and scrotum.”

This report did not come from Virginia, however, nor was it written by an acting assistant surgeon. It came instead from Governor’s Island, New York, and it was signed by Minor in his new capacity as an assistant surgeon in the U.S. Army. By the autumn of 1866 he was no longer a contract man, but instead enjoyed the full rank of a commissioned captain. He had done what most of his colleagues had failed to do: By dint of hard work and scholarship, and by using his Connecticut connections to the full, he had made the transition into the upper ranks of regular army officers.

His supporters, in Connecticut and elsewhere, were unaware of any incipient madness: Prof. James Dana—a Yale geologist and mineralogist whose classic textbooks are still in use today, worldwide—said that Minor was “one of the half dozen best…in the country,” and that his appointment as an army surgeon “would be for the good of the Army and the honor of the country.” Another professor wrote of him as “a skillful physician, an excellent operator, an efficient scholar”—although, adding what might later be interpreted as a tocsin note, remarked that his moral character was “unexceptional.”

Just before his formal examination Minor had signed a form declaring that he did not labor under any “mental or physical infirmity of any kind, which can in any way interfere with the most efficient duties in any climate.” His examiners agreed: In February 1866 they granted him his commission, and by mid-summer he was on Governor’s Island, dealing with one of the major emergencies of the postwar period: the fourth and last of the East’s great cholera epidemics.

It was said that the illness was brought by Irish immigrants who were then pouring in through Ellis Island: Some twelve hundred people died during the summertime scourge, and the hospitals and clinics on Governor’s Island were filled with the sick and the isolated. Minor worked tirelessly throughout the months of the plague, and his work was recognized: By the end of the year, though still nominally a lieutenant, he was breveted with the rank of captain as reward for his services.

But at the same time there came disturbing signs in Minor’s behavior, of what with hindsight appears to have been an incipient paranoia. He began to carry a gun when he was out of uniform. Quite illegally, he took along his Colt .38 service revolver, with a six-shot spinning magazine that, according to custom, had one of the chambers blocked off with a permanent blank. He carried the weapon, he explained, because one of his fellow officers had been killed by muggers when returning from a bar in Lower Manhattan. He too might be followed by ruffians, he said, who might try to attack him.

He started to become a habitué of the wilder bars and brothels of the Lower East Side and Brooklyn. He embarked on a career of startling promiscuity, sleeping night after night with whores and returning to the Fort Jay’s hospital on Governor’s Island by rowboat in the early hours of the morning. His colleagues became alarmed: This was totally out of character, it seemed, for so gentle and studious an officer—and particularly so when it became clear that he frequently needed treatment, or such as was available, for a variety of venereal infections.