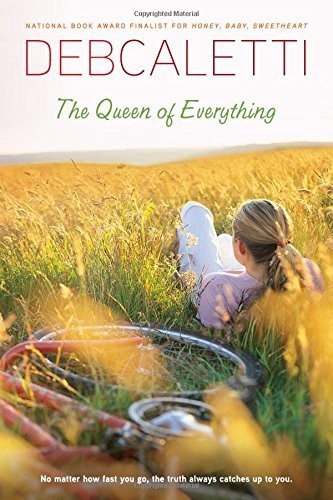

The Queen of Everything

Read The Queen of Everything Online

Authors: Deb Caletti

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Family, #General, #Social Issues

The Queen of

Everything

Deb Caletti

For my roots and branches -

Mom,

Dad,

Sue,

Warren,

Sam, and

Nick.

With love

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Anne Greenberg and Jennifer

Klonsky.

And to Ben Camardi, gratitude beyond

measure.

Chapter One

People ask me all the time what having Vince

MacKenzie for a father was like. What they mean is: Was he always crazy? Did he

walk around the kitchen with an ice pick in the pocket of his flannel bathrobe

every morning as he poured himself a cup of coffee?

Some ask flat out, as if it's their right to

know. Others circle it, talk about the weather first, thinking they're being so

sneaky when really they're as obvious as a dog circling a tree.

When they ask I always say the same thing. I

say, "He was an

optometrist

for God's sake. You know, the guy who sits

you in the big chair and says, 'Better here, or here?' The ones with the little

pocket-size flashlights?" And that's all I say. I try to keep it all in the tone

of voice. I don't even

2

add a,

If you must know, you insensitive

jackass.

Well I did say that once. I don't count it though, because it was

to an old man who probably had bad hearing.

What I won't do is tell anyone what he was

really like.

I won't say that when I think of him now, I see

him outside, at places he can no longer go. I see him mowing the front lawn,

wearing his University of Washington Huskies cap, holding his hand to his ear to

let me know he can't hear what I'm saying over the mower's engine. I see him

dumping the basket of clippings into the garbage can, small bits of grass

clinging to his sweatshirt. I see him watering the rhododendrons, his thumb held

over the end of the hose to make the spray less harsh.

And I see him--us--in our house. The house we

used to live in. I see him with his tie loosened after work, pouring himself a

glass of milk and asking how my history test went. I remember sitting next to my

father at the kitchen table, him trying to explain my math homework but making

it more confusing. And me, saying,

Oh, I see!

when I didn't, because I

didn't want to hurt his feelings.

I won't tell anyone his faults either. That he

swore when he fixed things and flirted too much with waitresses and swaggered

around more than he deserved to when he was wearing

3

a new shirt. Good or bad, I keep those things

to myself. I don't want those parts of him, the real him, to turn into something

cheap and meaningless. It would make me the kid with no friends, giving out

candy on the playground. People would grab up those bits of him like greedy

children with a roll of Lifesavers. They'd peel off a piece of him, roll him

around in their mouths for a few seconds, and then swallow and forget about

him.

Besides, that's not what people want to hear

anyway--that my father was just a normal guy whom I loved,

love,

with all

my heart. It makes them nervous. Because if he was normal, if he wore Old Spice

and liked nacho cheese Doritos, then why not their own fathers? Or themselves?

Deep Inner Evil--we like that. It's easier to accept than what Big Mama says,

which is that wanting things for the wrong reasons can turn anyone's life into a

marshmallow on a stick over a hot fire: impossibly messy and eventually

consumed, one way or another. People want to think that I lay in bed awake at

night, my heart pounding in fear of him. They don't want to know that I slept

just fine, dreaming I'd forgotten my locker combination just like

them.

Or that I went to live with Dad because he was

the regular one; that it was my mom who I was convinced was nuts. Claire was the

one I never wanted my friends to see. She had this

4

shaggy hair under her arms that always made me

think of a clump of alfalfa sprouts in a pita pocket. And you never knew when

she might suddenly flop out a boob to nurse Max, which she did once during a

parent-teacher conference to the shock of my new math teacher, Mr. Fillbrook. By

the look on his face I'm positive Mrs. Fillbrook always got dressed in the dark.

Or else she did that trick when you slip your bra through your sleeve every

night when she put on her nightgown. All Claire had to say about the whole thing

was, "If he was titillated, pardon the pun, that's his problem."

God.

When I lived with my mom, it was her house that

embarrassed me, never Dad's. Mom had turned our old house into a bed and

breakfast, which is one way to make a living on Parrish Island if you don't want

to rent kayaks or work the oyster beds. At Mom's house you never knew who was

coming or going. And Nathan's metal sculptures were spread all over the yard,

spinning like mad in the wind and hanging from the trees like giant Christmas

ornaments. Nathan is my mother's husband; he's ten years younger than she is.

He's also an "artist." His work is 'kinetic art for the outdoors." That's how I

thought of their life. Like it all belonged in quotation marks.

When I moved in with my dad,

that's

when

5

my life got normal. I moved into a regular

neighborhood with a regular house. I transferred from that goofy alternative

school I hated, where we made quilts and "worked at our own pace" and where the

teachers all wore sandals no matter what the weather, to Parrish High where you

had to sit in your seat and learn English and the kids weren't weird. I met

Melissa Beene, who lived down the block and whose parents had a big black Weber

barbecue and electric garage-door openers. Everyone in my dad's neighborhood

mowed their lawn and thought breakfast was the most important meal of the day

and got upset if their kids missed their curfews.

Anyway, evil. If anyone was truly evil in all

this, it was Gayle D'Angelo. She put that gun in his hands. I don't like to

think about her. I

hate

thinking about her. But Mom and Nathan and

everyone else keep telling me that it's

healthy

to get the feelings out.

Big Mama says that even salmon carry their life stories on their scales, the way

a tree does with its rings. And my old English teacher, Ms. Cassaday, claims

writing this out will be good therapy. "What is therapy after all," she says,

"but telling your tale to someone who won't get up in the middle?" So okay,

fine. Just so I don't suddenly fall apart one day when I'm thirty-five in an

aisle of the grocery store or something. Carried out kicking

6

and screaming while the ladies squeezing lemons

pretend they don't notice a thing.

I will think about her. And it will be all

right. Because, true, the story starts there, with Gayle D'Angelo. But it does

not end there.

I first met Gayle D'Angelo at the True You

Health Center. My best friend, Melissa Beene, got me the job at True You. We

worked after school, the occasional evening, and more hours in the summer. True

You is in a strip mall, in the new part of town that the original Parrish

Islanders hate. If you took one of those snoots who say they watch only PBS and

dangled a game show in front of their eyes, that's the kind of reaction I'm

talking about. I used to think the whole argument was stupid. My mother would go

on and on about the yuppies coming from Seattle and Microsoftland with their

plastic money, building plastic things, intent on destroying the spirit of the

islands. The San Juans had always been an escape from all that, she'd

moan.

"And what's with these minivans?" she said

once. "I feel like I'm in some sci-fi movie.

Revenge of the Pod People.

Invading the world in Dodge Caravans. You watch, those people are going to wreck

everything. I bet even the whales will get wind of what's happening and stop

coming around."

"That's what the farmers said when

you

7

hippies started moving out here, Claire," I

said. Parrish, and the other large islands of the San Juans, used to be mostly

orchards. There were still stretches of sprawling farmland and spots of gnarled

apple trees where the deer met up with their friends for garden parties. "And

what the Indians said about the farmers."

My mother glared at me. "Jordan," she

said.

Tm sorry," I said. I used to say this a lot,

especially when I wasn't in the least. "I just never got that, the way people

yelled about trees being cut down as they sat in their own cozy home in front of

a blazing fire."

"This is not about selfishness," she snapped.

"It's exactly the opposite. It's about having something pure and true, and

trying to protect its essence." This is the way my mother talked. She was

getting worked up, flushing the shade of a ripe peach. "What's happening is a

crime. An abomination. A

bête noire."

"What's that, a perfume?" I said.

She sighed.

"Sounds like a perfume. 'Purchase a three-ounce

bottle of Bête Noire and receive a one-ounce line minimizer and cosmetic tote as

our gift to you.'" I chuckled. I was happy with my misbehavior.

My mother stopped glaring. Now she only tilted

her head and looked at me oddly, as if I were, say, the produce guy from

Albertson's

8

suddenly in her home. It was a look that said,

I know I know you from somewhere, but for the life of me, I can't figure out

who you are.

She gathered up her long hair into a pony-tail,

held it in her fist, and set it loose again. Finally she said, "I should send

you to your room for the rest of your life."

"Too late," I had said.

I used to think a lot of stupid things. About

Parrish Island, about my parents. But Big Mama says thinking we're ever done

being stupid is the dumbest thought of all. Being occasionally stupid is just

part of the human job description, she says. Big Mama's voice is like molasses

pouring from a bottle. When she calls, I press that phone so hard to my ear,

it's as if I'm getting her strength right through the wires. And right when that

strength seems to be running out, there she is again, filling me back

up.

You can imagine how my working at True You got

under my mother's skin. I didn't always purposefully try to get under her skin.

I didn't. It's just that sometimes things can be too real. Too intensely real.

Too honest and bare. Like the way you feel looking into the eyes of someone who

loves you, or someone in pain. Or the way you feel when you hear beautiful

music. It can be like looking into the sun. You've just got to close your eyes.

Even go inside for a while. Or keep it all at arm's length with words like

crazy,

9

covering it with a smooth layer of

embarrassment. My mother and Nathan were like that. Parrish Island was like

that.

As I said, Melissa got me the job at True You,

and at the moment Gayle D'Angelo came in, Melissa was in the large weigh-in room

with Laylani Waddell. Laylani and her husband, Buddy, owned True You. Anyone who

names their kid Laylani is looking for trouble, if you ask me. You had to be

careful with Laylani. She and Buddy were Christians with a capital C, the type

who think they've got God's secret phone number. If you let so much as a

shit

slip, Laylani would start hiding these little religious bookmarks

with prayers and sunsets on them in your lunch bag and in your coat pockets. She

wouldn't say a word about them, either. I think she really believed we might be

so stumped as to who put them there, we'd start suspecting God

himself.

I could hear Laylani's voice coming through the

weigh-in room door. Her voice sounds the way a maraschino cherry might sound if

it could speak. The door was propped open with a small block of wood, the way

Laylani demanded. Large people overheated easily she always said. She worried

about this a lot. I think she had a secret fear one of the fat people might have

a heart attack on the premises and sue her and Buddy for the house and the RV

with the built-in shower. Melissa liked to get revenge for the

10

bookmarks by hiding this block of wood, which

would send Laylani scurrying around in a tizzy, sprayed hair releasing in

bunches as she searched for it underneath the furniture. Like a madwoman she'd

try other propping devices in the door, like the stapler, which would only slide

free and shoot across the floor.

When Laylani's inspiring pre-dinner lesson was

over, Melissa and I would do weight and measurement. In the meantime I was

copying an article, "Recipe for Success," that would be placed in new "team

member" folders. This is what people who joined True You were called, the idea

being that they were one enthusiastic group fighting a tough but conquerable

opponent-- fat--with the help of Coach Laylani. I sat on the edge of the

reception desk and read the article as the copy machine flashed and made its

kershunk-kershunk-kershunk

sounds. "It's your total diet over several

weeks rather than what you eat in a given meal or even an entire day that

determines whether you're eating healthfully and weight consciously," I read

aloud.

"No kidding," I said to the paper.