The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen (49 page)

Read The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen Online

Authors: Peter J. Bailey

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #Film & Video, #History & Criticism, #Literary Criticism, #General, #Literary Collections, #American

“And that’s why,” Helen Epstein continues in diagnosing her husbands fiction,” your real life is so chaotic and your writing is so much more controlled and stable.” Allen’s four 1990s comedies are characterized largely by a “controlled and stable” filmic style which symmetrically frames the movies’ prevailing affirmations of human love;

Deconstructing Harry

reverts to the frazzled cinematography

of Husbands and Wives,

self-consciously awkward jump cuts replacing the earlier film’s use of an untethered steadicam in order to stylistically evoke the emotional fissures and modal discontinuities of its plot. Helens characterization invokes once again the formulation which, Modernists asserted, privileges art above life, but Allen’s film finds little justification for celebration in Harrys restoration of literary powers, the films last images picturing him alone at his typewriter, beginning his new novel, while the slightly derisive “Dream a Little Dream of Me” which glossed his imaginary honorary degree ceremony continues to play on the soundtrack. The best that can be said of Harrys redemption is that its the only form in which redemption could exist for him—through art. In order to save himself, he has reverted to his late-adolescent attitude of “not caring about the real world” and caring” only about the world of fiction,” enacting this reversion by projecting a new novel blurring distinctions between his art and his life. Unblocked, Harry Block begins to craft a narrative delineating” a character too neurotic to function in life, but [who] can only function in art,” his novel very likely resembling the film narrative whose ending we have just watched. The ambivalence of Harrys salvation-through-art is nicely summarized in Cecilia’s

Purple Rose of Cairo

description of her similarly redemptive affair with a fugitive from a Hollywood movie: “I just met the most wonderful new man. He’s fictional, but you can’t have everything” (p. 434).

In an important sense, the sour cinematic parable

of Deconstructing Harry

is a thoroughly distorted yet completely revealing self-portrait of Woody Allen. In its testily jump-cutting dramatization of the conflict between life and art,

Deconstructing Harry

effectively epitomizes the filmmaker’s irresolvably ambivalent sense of the insufficiency of salvation-through-art—and of the artist’s inescapable necessity for affirming that possibility in the absence of any other alternative.

19

From the Neck Up

Another Woman

and

Celebrity

The real ones want their lives fiction and the fictional ones want their lives real.

—Press agent in

The Purple Rose of Cairo

As Woody Allen prepared to enter the twenty-first century, he was not a san-guine spectator of the realm of cell phones, facial makeovers, and celebrity worship he believed New York City had become. Whereas in

Manhattan

he had dramatically juxtaposed breathtaking vistas of the city and the soaring melodies of George Gershwin with the shallow narcissism of the city’s inhabitants, in

Celebrity

Manhattan seems to have dwindled to the size of its characters’ sensibilities, New York merely providing an urban backdrop for their self-promoting and self-serving erotic pursuits. Like Isaac Davis in

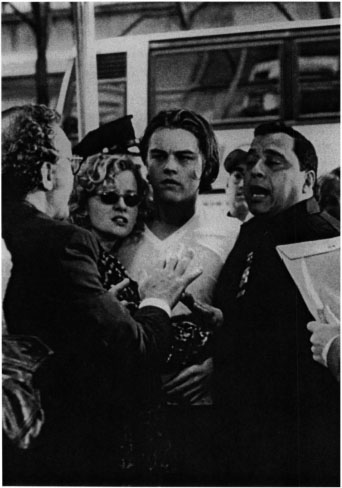

Manhattan, Celebrity’s

protagonist, Lee Simon, is writing a book “about the values of a society gone astray”; even more transparently than Isaac, Lee is as much a symptom of those strayed values as their critic. Isaac accuses Yale, his friend and doppelganger, of mercurial, contradictory attitudes—wanting to complete his book on O’Neill’s plays, wanting a Porsche—which closely parallel Lees conflicts: he longs to write a substantial novel satirizing the media-poisoned world he inhabits, but he is clearly more enthusiastic about cutting a figure in that world as he drives through it in his 1967 Aston Martin. Similarly, Lee wholeheartedly endorses the complaint of spoiled Hollywood star Brendan Darrow (Leonardo DiCaprio) that the scripts he receives lack integrity, but Lee then meekly acquiesces to every change in his own script—about “an armored car robbery with a very strong personal crisis”—which might pique Brendan’s interest in the property.

Manhattan,

Allen told Frank Rich, deals with trying “to live a decent life amidst all the junk of contemporary culture—the temptations, the seductions. So how do you keep from selling out?”

1

Lee Simon doesn’t. Allen’s mood as he produced this sour satire is best summarized by the fact that “amidst all the junk of contemporary culture,” art in

Celebrity

doesn’t stand a chance.

Through the cognitive dissonances between art and life that Lee experiences throughout

Celebrity,

Allen is making an argument with which we are familiar: art is too much the product of corrupt human beings to be anything other than corrupt. What appears to be new in

Celebrity

is the dramatization of the ways in which life and art are imbricated in each other. In fact, Allen established the terms of their interpenetrability in

Husbands and Wives,

Gabe Roths explanation to his interlocutor/analyst of the relationship between his art and erotic pursuits provides a key to one of Lee’s central confusions throughout

Celebrity

. “Maybe because I’m a writer…. some dramatic or aesthetic component becomes right, and I go after that person.” Gabe continues, “Its almost as if there’s a certain … some dramatic ambiance … it’s almost as if I fall in love with the person and in love with the situation in some way, and it hasn’t worked out well for me at all.”

2

As we’ve seen, Gabe’s largely unconscious laminating of life and art “hasn’t worked out well for [him] at all” because it demands that his life replicate the dynamics of dramatic narrative. Gabe “grew up on movies and novels in which doomed love was romantic,” Judy Roth explains in characterizing her ex-husband to the film’s narrator/interlocutor; consequently, Gabe is attracted to the “kamikaze woman,” Rain,

because

she’s trouble, because, as he acknowledges, her siren’s song ringing in his ears is the sound of his “$50,000 of psychotherapy dialing 911.” In a moment of rationality, Gabe resists indulging himself in the romantic potentialities of the candlelit, lightning-illuminated occasion of Rain’s birthday, withstanding the desire to play out a “scene which cried out desperately to be played.” As if to protect himself against further temptations to confuse his art and life, Gabe at the end of

Husbands and Wives

is working on a “less confessional, more political novel,” one, presumably, whose more inclusive perspective on human interaction will provide less inducement to make his life mirror its contours. Numerous reviewers construed the ending of

Husbands and Wives

as dramatizing the obverse of Allen’s real-life choice, more than one of them upbraiding him for hypocrisy in having his protagonist assume the moral high ground on the issue of May-December relationships in a way that Allen did not. Such moralistic confoundings of art and life were probably the inevitable harvest of a film career so devoted to dramatizing life/art convergences, but it’s not as if Allen’s films don’t provide significant admonitions against similar conflations of the artistic and existential. In movies neatly spaced five years on either side of

Husbands and Wives,

Allen depicts protagonists whose midlife crises prompt them to surrender to the very confusion Gabe evades.

Another Woman

and

Celebrity

create characters whose lives are blighted by their incapacity to keep art and life separate. The very real ambivalence of Allen’s feelings toward the human capacity to confuse art and life is epitomized by the fact that in

Another Woman

he por-trays Marion Post’s blurring of the two with a psychological depth that pro-vokes sympathy for her in the viewer, while dramatizing Lee Simon’s parallel failure in such one-dimensional terms as to make him seem an unlikable projection of the hollow, media-crazed world he inhabits and abhors. Between the densely philosophic naturalism

of Another Woman

and the tabloidal shallowness of

Celebrity,

Allen delineates a vision of contemporary life spanning auteurial sympathy and nearly fathomless cynicism.

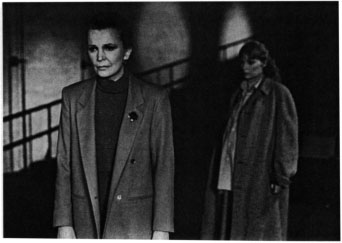

Marions opening voice-over narration immediately establishes that she (her interior life, really) is the central focus of

Another Woman’s

narrative. It is clear from the beginning that her opening attitude (she’s not afraid of uncovering “some dark side of her character,” but if something—her life—seems to be working, she prefers to leave it alone) is going to get rebuked in the film, obliging her to confront “some dark side of her character.” That hers won’t be a fruitless journey into the dark is signaled repeatedly by the spiritual helpers who emerge to assist Marion along the path toward self-confrontation.

Marion (Gena Rowlands) is a professor who rents a one-room flat in which to write her book on German philosophy, rationalizing the rentals necessity on the grounds that when she begins such a project she must cut herself off from everything but the work. On her first morning of academic seclusion, however, her work is interrupted when she hears emanating from a wall vent a psychoanalytic session in progress in which a client is acknowledging ‘some dark side of his character’ by admitting to entertaining sexual fantasies of males while masturbating.

3

Because homosexual temptation is not her conflict, Marion manages to silence these unsettling self-exposures very simply by propping sofa cushions against the vent. The self-revelations of a female patient in a session later that afternoon prove impossible for her to block out, however, because they impinge so closely on Marions repressed condition. This character, played by Mia Farrow, is never actually named in the film, but the closing credits designate her Hope, identifying her with a Gustav Klimt painting she and Marion discuss in an antique store depicting a young woman who appears to be as pregnant and despairing as Marions companion. “It was as if a curtain had parted,” Hope tells her analyst, both anticipating and precipitating Marions self-confrontation, “and I could see myself clearly, and I was afraid of what I saw and what I had to look forward to.” Hopes candid confessions of despair and self-doubt challenge Marion’s affirmations of equanimity, prodding her on toward the acknowledgment that her marriage is a union of mutually lonely partners and to the realization that what she has construed in her own behavior as rationality is an emotional frigidity. “She’s led this cold, cerebral life,” Marion overhears Hope describing her in a later psychoanalytic session, after the two women have met and talked, “and has alienated everyone around her … I guess you can’t keep deep feelings closed down forever. I don’t want to wake up when I’m her age and find my life is empty.”

Hope’s role as spiritual initiator is reinforced by others in the film equally committed to facilitating Marion’s self-confrontation. Marion’s sister-in-law (Frances Conroy) surprises her by asserting that Marion’s brother hates her both for her worldly success and for her lifelong condescension to his professional failures. “You’re such a perceptive woman,” Lynn tells her, “how can you not understand his feelings?” At a party, Marion and her husband, Ken (Ian Holm), listen to the boozily uninhibited revelations of another couple (Blythe Danner and Bruce Jay Friedman) concerning their sexual couplings on their living room floor, the conversation spurring Marion to wonder if there is any passion left in her marriage, or in her life. This worry is exacerbated by her recurrent memories of Larry Lewis (Gene Hackman), a novelist who attempted to dissuade her from marrying Ken so that she might marry him instead. Her insistence on honoring her previous commitment prompted Larry to accuse her of deserving Ken, because she is as smug, self-important, and passionless as he is. (Larry’s indictment, while largely rejected by Marion because it is sparked by passion, is the one which cuts deepest, requiring that Marion earn his benediction if her crisis—like the film’s plot—is to achieve resolution.) Trailing Hope through the streets one evening, Marion loses her but encounters a friend from college, Claire (Sandy Dennis), who drunkenly confesses her resentment of Marion for having alienated the affections of a man Claire loved while they were undergraduates at Bryn Mawr. Marion’s stepdaughter (Martha Plimpton) has real affection for her, but Marion is depressed upon overhearing the girl tell her boyfriend that her stepmother “is a little judgmental—she stands above people and evaluates them.” When Marion dreams about her first husband’s rage at her decision to abort their child—all she cared about, he contends, was “your career, your life of the mind”—her encounter with the “dark side” of her personality is complete.