The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen (52 page)

Read The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen Online

Authors: Peter J. Bailey

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #Film & Video, #History & Criticism, #Literary Criticism, #General, #Literary Collections, #American

The music Emmet—jazz guitarist Harold Alden, in fact

12

—creates justifies his repeated insistence that “I’m an artist, a truly great artist,” but every attempt the other characters make to discover in him a human being commensurate with the artist comes up empty. Seeking to illuminate the mystery of artistic creativity, Blanche asks him, “What do you feel when you’re playing? What are your real feelings?” to which Emmet, after brief reflection, replies, “That I’m underpaid.” Emmet epitomizes once again the skepticism about the superiority of art and artists we have tracked through Allen’s oeuvre;

Sweet and Lowdown

allows Allen to revisit the notion introduced in

Bullets Over Broadway

that artistic creativity and human savagery have identical sources by paralleling Emmet’s explanation of his musical gift with the explanation a hit man uses to account for his aptitude for rubbing out his boss’s enemies: their genius “came naturally.” When the hood (Anthony La Paglia) with whom Blanche has begun an affair asks her who is the better lover, she responds, “Emmet has a violent side, but it all turns to passion in his music. With you,” she tells Al Torrio, “it’s like I’m looking into the heart of darkness. Emmet is an artist, and because he’s an artist, he needs no one. I mean, even in making love, he seems to exist in a world of his own.”

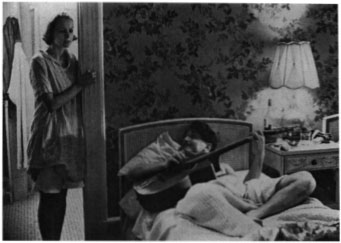

What provisionally redeems this artist whose favorite recreation is shooting garbage dump rats and watching freight trains, briefly drawing him out of the “world of his own,” is the same thing that saves Leonard Zelig: “the love of a good woman.” Emmet initially wants nothing to do with Hattie (Samantha Morton), one of two women whom he and his drummer pick up on a day off. When he discovers that she doesn’t speak, has suffered a deprived childhood, and is mentally limited, he dismisses Hattie as “a goddamned mute orphan halfwit,” imagining that he’s being sympathetic in asking if she lost her voice because somebody dropped her on her head. He softens toward her considerably when his playing of “I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles” utterly transfixes Hattie, his music affecting her in a way that—despite his assertion that “I let my feelings come out in my music”—it never really does him. Because of the intensity of her response to his playing and the safety her voicelessness offers him, Emmet opens up to her as he does to no one else in the film, telling her of his father’s abusive treatment of him, of his feeling that his mother’s singing was “the most beautiful thing I ever heard.” Henceforth Hattie accompanies Emmet to every performance, her face miming inestimable joy as she happily devours whatever dessert the restaurant he’s playing in offers as gustatory complement to her pleasure in listening to his music. (“Hattie’s so full of stuff: How can I convey all that she’s thinking?” Samantha Morton wondered in preparing to play Hattie. “Learning lines is the easiest thing in the world. This was the hardest part I’ve ever played.”

13

) Morton’s Academy Award-nominated performance is among Allen’s films’ most luminescent cinematic achievements, one that is by no means minimized by

Sweet and Lowdown’s

construction of Hattie as a thoroughly allegorical figure.

A few reviewers of

Sweet and Lowdown

interpreted Hattie’s muteness as symptomatic of misogynistic attitudes in Allen, contending that he—like Emmet—values her primarily for her passivity and inarticulateness.

14

A less ideological reading of the film construes Hattie instead as an embodiment of the audience to which Emmet is so Modernistically indifferent. Viewed in these terms, Hattie’s incapacity to talk reflects that audience’s parallel want of self-expression; her rapaciousness (both appetitive and sexual) invokes the audiences infinite hungers, while her abject devotion to Emmet images up the audience’s dependency on artists to translate their most inchoate impulses into beauty.

15

(Like Joey of

Interiors,

Hattie is utterly lacking in artistic capacity; unlike Joey, who suffers her inexpressiveness as a terrible debility, Hattie is thoroughly content to let Emmet’s guitar music be the voice she doesn’t have.) Emmet anticipates the link that the film subsequently forges between Hattie and the artist’s audience when he warns Ann, “I enjoy the company of women—I love ‘em. Its just I don’t need ‘em. I guess that’s just how it is if you’re a true artist.” For Emmet, as for Allen, a “true artist” is focused on aesthetic creation—on achieving “the authenticity of the scene”—rather than audience reception or the feelings of others. Consequently, Emmet perceives women throughout the movie as a threat to his artist’s autonomy, cautioning them—much as Harry Block admonishes Fay in

Deconstructing Harry

—against falling in love with him since his art must always come first. Because Hattie so clearly comes to love the artist through loving his art, Emmet is unusually drawn to her, justifying his attraction by offering a slighting view (approximating Allen’s own) of her and the audience of which she is a member and symbol: “You don’t have to be bright,” he assures her after inviting Hattie to hear him play, “music’s for everybody, the smart or the dumb.”

Modernist aesthetics repeatedly insist on the shabbiness of life-as-it-is, of the intolerableness of existence unimbued by art’s elevating, clarifying redemptions, and so the film’s embodiment of the unleavened audience must not only be figuratively and literally dumb, but must also lack any hint of sublimity or glamour. Appropriately, then, Hattie is a laundress. Desperately seeking to remedy the lack of glamour in the woman with whom he is spending more and more time, Emmet takes Hattie shopping for outfits he hopes will complement his own extravagant sartorial tastes, but for all the stylishness of the flapper garb he buys her, Hattie continues to look like the laundress she was when he met her. Her face alone, in the moments of pure ecstasy Emmet’s music instills in her, lifts her beyond the pedestrian circumstances of which she is product and victim into an almost extrahuman prettiness, recalling Cecilia’s hapless dependency on movies to elevate her life out of the Depression’s desperate woes in

The Purple Rose of Cairo

. Troubled by the incompatibility of Hattie to his self-image and aspirations, Emmet banishes her from a performance when a wealthy sybaritic dowager seduces him with a stick of “tea”; the upshot of this betrayal of Emmet’s ideal audience is that he wakes up in Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania, three days later, his dereliction having cost him his gig. His more final rejection of Hattie/his audience will figuratively cost him his life.

Chastened by this experience validating his career’s dependency upon Hattie, Emmet grudgingly agrees to take her with him and drummer Billy Shields (Brian Markinson) to Hollywood for the shooting of the “All of Me” short. An amateur talent contest in rural Midwest America they discover en route to California allows Allen to substantiate the movies identification of Hattie with the artist’s audience. The other contestants competing for the cash prize are 1930s U.S. heartland versions of Danny Roses acts: they do bird calls, play saws and spoons, or earnestly warble nineteenth-century faux operatic numbers, all of which amuses professional musician Emmet no end. These people belong in the audience, his smirking attention implies, and Hattie grows increasingly anxious at the blatant condescension he radiates toward these performing rubes with whom she clearly identifies. When his turn comes to perform, Emmet takes the stage, introducing himself as a birdseed salesman, and proceeds to play a dazzling rendition of “12th Street Rag” calculated to blow the room away. The audience is slow to respond to Emmet’s virtuoso performance, their subsequent applause acknowledging his ability while their withholding of the prize money reflects how little they can appreciate his jazz stylings. As the scene shifts to the three travelers eating sandwiches next to Emmet’s car on the roadside that evening, Shields expresses relief that Emmet’s act didn’t get them tarred and feathered. “The next time you’re gonna hustle somebody,” he admonishes Emmet, “don’t play so great.”

Emmet complains in self-defense, “I can’t remember the tunes if I play badly.”

Emmet’s elitist incapacity to accommodate his art to his audience’s limitations is amusingly rehearsed here, an attitude which Allen owned up to in an interview contemporaneous with the movie’s release.

16

More significant is Hattie’s anger both at the scam and Emmet’s attitude toward the contest audience. He wonders if Django ever “hustled any suckers” as he has just tried to do, and when Hattie’s face collapses in a resentful pout at his characterization, he tells Shields, “Look at her—she’s frownin’—she doesn’t like it. Well, they deserved it—they were jerks.” Guiltily aware that he’s implicitly attacked Hattie, Emmet briefly softens, explaining to Shields, “She’s too good-hearted, a genuinely sweet person. I like that—I respect it.” He won’t, of course, emulate Hattie’s nature, because “It won’t get you anywhere in life.” For Hattie, Emmet’s music is precious for its honesty and sincerity; using that music to sucker what Emmet characterizes as “jerks” is a betrayal of everything she values in his art and in him. He makes light of her irritation, obliviously proceeding to recount to Shields a dream he’s had about “being discovered in Hollywood as a major star” while they’re filming the “All of Me” short. His egotism and self-isolation are precisely what will prevent him from becoming “a major star” in either jazz or Hollywood, the roadside scene prefiguring the inevitability of the Emmet/Hattie breakup by dramatizing the irreconcilable differences between their perceptions of his art, manifested most clearly in his Modernist’s repudiation of art’s accountability to other human beings, to the audience. The scene closes with Emmet reprising his tendency to parabolize his audience as women threatening him with entanglement: “You gotta keep your guard up,” he warns Shields, “[if] you don’t, the pretty ones get their worms into you, and then its over, you’re done. Particularly if you’re an artist. I’ve seen too many guys crying in their beer. Me, I’m gonna be a star.” (As if intuiting that this desire excludes rather than depends on her, Hattie stormily frowns.) In subsequent scenes, having rejected Hattie, Emmet lets a pretty one get her worms into him, he never becomes a star, and he ends up crying in his beer at a roadside joint before decimating the instrument he blames for having failed to win him the stardom he craved.

The “pretty one” is Blanche, a Chicago socialite beauty who dresses as flamboyantly as Emmet does and who has artistic aspirations of her own as a writer. Emmet is deep into his relationship with her before we learn why Hattie has vanished from the film. (The movie noticeably loses a level of intensity with Hattie’s disappearance, replicating the emotional impoverishment that Emmet experiences as a consequence of discarding his link to human emotionality in the name of artistic freedom.) Emmet tells Blanche that one night he just took off, leaving Hattie five hundred dollars to remember him by He doesn’t explain that it was the word “love” written in her “chicken scratch” on a birthday card which precipitated his flight: having read Hattie’s card, he rushes off to the bathroom to be sick. Blanche sizes up Emmet immediately, recognizing that their relationship is predicated on the fact that “any woman would be second to his music. He wouldn’t miss me any more than the woman he abruptly left. He can only feel pain for his music—such is the ego of genius.” The best that Emmet can manage in providing Blanche with a rationale for abandoning “the woman he abruptly left” is “I needed more than Hattie.” Nonetheless, he calls out Hattie’s name in his sleep one night, and when Blanche informs him of his sleeptalking the following morning, he asks her to marry him in a transparent attempt to deny the powerful hold Hattie continues to exert upon him. In marrying Blanche, Emmet is re-enacting Isaac Davis’s error in

Manhattan

of favoring sophistication and erotically enticing instability over innocence and genuine sweetness, prompting jazz critic Nat Hentoff (one of a chorus of jazz enthusiast narrators serially projecting the movie’s Emmet Ray yarns) to apostrophize, “There was always something unreal about it. Talk about a doomed relationship!”

Within weeks of their marriage, Emmet grows impatient with Blanche’s incessant interrogations of the sources of his art and creativity. She defends her curiosity by explaining, “I’m trying to analyze your feelings so I can write about them.” “Look,” he responds, “I’m your husband. I’m not some goddamned book idea.” Her perception of him as “a goddamned book idea” more than an erotic partner apparently persuades Blanche that she needs more than Emmet, sparking her affair with Torrio the gangster, which effectively ends her marriage to Emmet. For his part, Emmet comes to see that, in addition to trading in genuineness for self-consciousness, his replacement of Hattie with Blanche meant exchanging a sincere, responsive audience for a prying and invasive music critic. Blanche exaggerates the value and significance of Emmet’s art in precisely the ways that Allen believes film and literary critics do in explicating his movies: she/they/we make too much of art, seeking answers to unanswerable questions like Blanche’s: “The sound, the beat, the ideas—where do they come from?” Allen’s Emmetesque response might be that they come from the pencil with which he writes the first drafts of screenplays on yellow legal pads. Hattie—like the ideal audience of Allen movies, who watch and then go home and quietly digest—never asks any of these questions: for her, Emmets art is what it is—a simple and uncomplicated source of human pleasure. For her, his music is like New Orleans jazz as Allen defines it in

Wild Man Blues:

“There’s nothing between you and the pure playing—there’s no cerebral element at all.” Hattie’s face is an infallible critic of such music: it registers whether the music works or not.