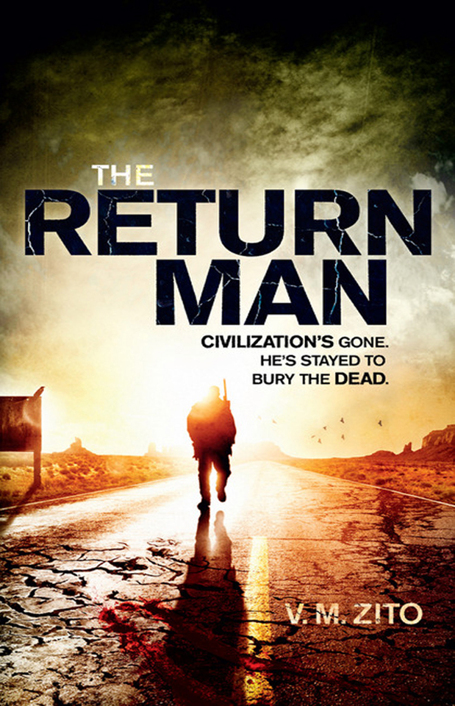

The Return Man: Civilisation’s Gone. He’s Stayed to Bury the Dead.

Read The Return Man: Civilisation’s Gone. He’s Stayed to Bury the Dead. Online

Authors: V. M. Zito

Tags: #FIC002000

For Krissy and Maggie.

You brought me back to life.

1.1

The corpse crouched in the shallow mud-water along the lake, shirtless and saggy chested, grabbing at minnows that darted between the green rocks. Marco studied it through his binoculars. Sometimes the dead surprised him–so quick with their hands, but so uncoordinated. Like toddlers. He watched the corpse strike and come up empty, then again, gawking at its palm while its reptilian brain groped to understand the failure. Failing at that, too, it splashed after the next silver flash of fish.

Marco squinted.

There.

On the dead man’s left hand.

A wedding ring.

He zoomed in on the ring. Jewellery was a godsend for making the ID. Skin fell off, hair fell out; fat men rotted themselves thin, and thin men ballooned with gas and bacteria. But if you were lucky enough to find the corpse with original jewellery, some identifiable piece that hadn’t been torn or bitten off, then you had your proof. Bring the jewellery back, and nobody disputed you’d done the job.

Down below, the corpse shoved its hand again beneath the water, stirring up the mud.

‘Come on,’ Marco muttered. ‘Come on, show me.’

The corpse splayed its fingers out for inspection, as if it had heard.

Which, of course, it couldn’t have. The tree blind where Marco had camped for three days now was a cautious two hundred yards up the mountain–tucked high into a young lodgepole pine, plenty of coverage, long green needles to disguise the canvas assembly. The platform was only five feet wide, five feet long; with all his gear there wasn’t enough space to stretch his legs while sleeping, but cramped muscles in the morning were a fair trade for the safety of altitude. The perch was accessible only by the iron spikes he’d driven into the trunk at intervals–impossible for a corpse to climb.

He’d learned to build the blind from a hunting magazine scrounged out of a dark Barnes & Noble a few months back, with parts from a ransacked Sports Authority. His Cornell education was officially useless; hunting magazines and topographical maps were the new required reading. Back before civilisation tanked, he hadn’t known an ounce of shit about outdoor survival. Now he went nowhere without a yellow, dog-eared copy of

Camping for Dummies

in his backpack.

A sharp, tiny pain speared his neck. He slapped a biting gnat, crushed it into his skin.

Christ.

He felt dirty and ripe. He’d been tracking this same corpse for almost a month. And the hike to the lake had been especially draining. He’d had to ditch the Jeep twenty miles south, where the mountain road had been blocked by the wreck of a thirty-foot Ryder truck. The trailer had wedged sideways between the trees–years ago, judging by the corrosion along the torn bed. Mildewed furniture, smashed electronics, scraps of orange-rusted metal strewn everywhere. In the cab sat the driver, skeletonised, arms eaten. Some idiot taking all his toys with him during the Evacuation. Flying hell’s bells down the twisty road, losing what control he had left.

The wreckage was impossible to clear, and the forest too dense for off-roading. On the map, Marco had measured an

alternate drive to the lake–three hours of circumnavigation that would burn a dangerous amount of gas, which was already in short supply. And so he’d decided to risk the remaining distance on foot, backpacking for a day with his gun drawn.

Compared to that, the tree here was a safe haven. From a height he enjoyed a clear view down over the forest, to the water, to the shore–past the man-made beach, the docks, the rustic vacation cabins clustered at the western inlet of sparkling Lake Onahoe. All calm.

Still, he now felt a twitch of unease, as if something weren’t right. He exhaled and studied the ring on the corpse.

Grimy, but the thick gold band was visible enough. Twelve millimetre or so. Square diamonds in a milled linear pattern, a fit for the description Joan Roark had given. Wives were good like that, he’d found. Men struggled for details–funny how they always remembered the price–but the women? They’d draw a ring from memory if you gave them pen and paper.

With his thumb, Marco idly played with the platinum band on his own left hand. It wobbled on his underweight finger. Only a matter of time, he knew, before it slipped past his knuckle in the middle of some craziness and plunked to the ground, unnoticed, gone. He had to start eating more, stop wasting away. Until then he should just take the ring off, store it back at base when he was on a job–or maybe get a chain, wear it around his neck like a dog tag.

Perfect, right? A reminder why he fought this war.

Danielle—

He didn’t allow the thought to finish. He tucked the binoculars into the mesh side pocket of his pack and refocused his mind.

The corpse.

Yes, there was a good chance Marco had found Andrew Roark.

He glanced at the printout tacked to the canvas beside him, a colour photo Joan had scanned and sent from her home in the East, in the Safe States. Roark when he was alive.

The photo was a headshot

–headshot

, Marco thought wryly,

always aim for the head, the only way to kill a corpse for good

–taken from the annual report of Roark’s company, Tylex, some big Fortune 500 number. Andrew J. Roark, CFO, an executive in his fifties. Sharp suit, double chin, a chubby neck squeezed into a starched white collar.

Roark’s cheeks were tinged red, his nose big with a round bridge that made him look like a large goofy bird. But friendly, Marco had decided, a guy who laughed a lot. A good-sounding, unguarded laugh–a guy who didn’t feel comfortable being boss, a guy who wore a baseball cap at the company picnic and wanted the lunchroom people to call him Andy. His eyes were a bright, insightful blue; his short hair glistened silver on the sides and dark across the top.

The corpse below Marco had blind white sacs for eyes, a few strands of hair on a rotten scalp.

But the rest is right

, Marco thought. If you used your imagination. If you ignored the toll of two postmortem years, the skin mottled like bad cheese now, the ears shrivelled, the tip of the nose missing where something had gnawed the cartilage. Ignore all that, and what do you see?

Marco nodded. He was almost certain the thing down there was Roark. And yet…

He couldn’t know for a fact.

Not until he saw that ring up close.

Moving slowly to minimise noise, Marco reached down next to himself in the blind and retrieved his rifle–a sleek Ruger 1-A he’d been lucky to find last year beside the mutilated body of a hunter in Utah. A good weapon. Long-barrelled but not too heavy, built for mountain killing, accurate at three hundred yards. Serious punch.

He trained the scope on the corpse. Miraculously, it had caught something. A frog hiding in the mud. One flipper, crooked and green, popped from the corpse’s fist, kicking at the air. The dead man flattened its hand against its mouth, shoving mud and frog inside, and bit down with a vicious jerk of the head. Brown sludge oozed from its teeth.

Marco shuddered. Bad luck for Kermit there. That was the problem with hiding places–down in the mud, up in a tree.

You think you’re safe, until you’re not.

The joints in Marco’s neck cracked as he scanned the forest below him and to the sides, searching for irregular shadows between the straight charcoal trunks. He listened for the crackle of feet dragging through dead leaves. But everything sounded right, looked right. Even the air smelled like the drizzly rain that morning, like clean pine. No trace of the giveaway stink that permeated an area when corpses gathered together.

But it worried him that the dead were good hiders, too. Sometimes they seemed to come from nowhere. And from experience he knew that one rifle shot could draw a crowd.

As remote as the forest seemed, the town of Wilson was just over the mountain, five miles down Route 78. Wilson, population five thousand–

former

population five thousand–an oasis in the Montana wild, catering to the summer lake vacationers who once flocked here.

The four-aisle grocery store, the lone movie theatre, the video store still packed with titles on VHS. Marco had resisted the temptation to pass through town for a supply boost on his hike. Instead he’d cut a wide path around. Places like Wilson were trouble. God forbid he stir up five thousand corpses. Christ, as far as he knew, they were out here already, enjoying a nice walk in the woods. Any careless sound could attract a pack, clamouring like dogs around the bottom of his tree, and he’d have to waste bullets–or worse, they might keep coming, outnumbering his ammo. He’d be stuck where he was, while Wilson held a goddamn town meeting below him.

Damn it.

He hated taking a shot unless he knew.

He concentrated his memory on the photo album Joan Roark had shown him. The trajectory of a man’s life. Andrew Roark, younger, thinner–even his nose looked smaller–in a white tux on his wedding day, black hair combed tight to his scalp, cigarette tucked in his grin. Roark through the years, turning older, heavier, better dressed, in a better house. Birthdays, Christmases, trick-or-treating in a scarecrow costume with the kids. Roark again in his fifties, at a banquet table, beaming, arm around Joan, champagne flutes before them on a white tablecloth. His hand held up three fingers for the camera. ‘Our thirtieth anniversary,’ Joan had said.

And their last.

But it was the vacation snapshots Marco remembered most. Decades of them. Andrew and Joan at the lake. The first photos were just the two of them, newlyweds. In a canoe, on the beach, cuddling in a hammock on a cabin porch. Then joined by an infant, then another. The kids aged, and then it was grandkids on rafts, rolling on the lawn, fishing on the dock with Roark. In one of the last pictures, Joan and Andrew in the canoe again, waving back at the camera.