The Ride of My Life (26 page)

Steve and I started working with ESPN2 to run contests. We felt an overwhelming need to make fun of every policy that was uncomfortable, too strict, too pointless, or too stiff. At the first BS/ESPN2 comp, I printed up T-shirts for the riders that featured the slogan

TV is

YOUR FRIEND

.

The shirt artwork also featured a receipt with a list of tricks, and the cash equivalent those tricks were worth. Every chance we got, we poked fun of ourselves and the network. For every rule, we made up an antirule. If the network proposed anything too outrageous—like when they said they wanted to discontinue flatland coverage—we told them no way and gave them a long list of reasons why they were obligated to support the ground guys. When they said they wanted to eliminate the entire amateur classification, we pointed out that without an am class, there would be no pros. Even in the planning and organizational phase, the network was constantly scratching their heads when dealing with Steve and me. For our first dirt jumping event, Steve sent ESPN2 a materials list for the things we’d need. The list included dynamite, gasoline, beer, a steamroller, and strippers. Over time, the network began to understand our stupid humor and passionate arguments, and the events improved. We never did get any dynamite, though.

But even by making the contests better, I realized that it would only get me so far in my fight to portray and explain bike riding to a mainstream audience. If I was going to succeed in making the masses understand our sport, I’d need to learn TV production and be able to show there was more to life than contests. I began to bug Ron about taking a lifestyle approach in their coverage, to show the personalities and inspirations in action sports. He had begun to trust me enough to know my motives and instincts were pure and that whatever complaints I had about the way ESPN2 did things were ultimately for their own good. His response to my request for a lifestyle show was to give me the rope to hang myself—he offered air dates in a prime-time slot.

With the green light to produce a TV show for an audience of millions, I was in trouble. I didn’t know how to program my VCR to get the clock to stop flashing. But I could use a computer and knew the basics of video camera point and shoot documentation. What I needed was something to practice on, so I concocted a project to bring me up to speed on making lifestyle-based entertainment that would bridge the gap between the bike stunts crowd and a broader audience. I set up a Media 100 editing system in my basement and told the Hoffman Bikes crew to get ready to do some filming. “Order a monkey costume,” I said to Steve. “We’re makin’ a movie.”

As an action sports production,

Until Monkeys Fly

confused the hell out of most bike riders. Hoffman Bikes had the best team in the world, which meant it would have been a no-brainer to pack sixty minutes full of sick trick clips cut together to a thumping soundtrack and progressive graphics. Instead, there was Rick Thorne using handlebars as kung fu weaponry to pound down a jock with a mullet. I had Kevin Robinson rock it like Sonny Crockett, wearing no socks and a sport coat, driving recklessly to

Miami Vice

music and beating up patio furniture. I insulted vegans and animal lovers alike by having masked vandals graffiti “Eat Meat” on cows. Taj, one of the best jumpers in the country [and a devout vegetarian], was relegated to portraying a shoeless, dirt farming hick. For most of my own appearances in the production, I sported a galactic space helmet/salad bowl and a flamboyant fake moustache. Adopting a gruff accent, I commanded a time-traveling primate to steal bike parts in a plot that revolved around the central character, monkey boy. Steve was forced to dress up as monkey boy and partake in a variety of ridiculous scenarios, including humping legs, playing Tetris, break dancing in public, and at one point invading a karaoke bar wearing the suit and screeching wildly [the bar patrons were

not

thrilled]. The humor was beyond corny—it was cornography. Despite the video’s flaws, there was also some decent riding in between the skits. But I took a heap of flack from the bike community upon the release of

Until Monkeys Fly

. Which was perfectly fine with me. I’d learned what I set out to do: make a TV show.

My pitch to Semiao was to showcase the pioneer spirit of people who ruled — whether they were into snowboarding, bikes, skateboarding, music, or miscellaneous danger. I wanted interviews, documentary footage, travel coverage, humor, and music reviews in the part of the mix. At first, the network execs balked when they read my treatment. “This is ESPN2, not MTV,” they said, concerned about bringing music on the strictly-for-sports-nuts channel. I asked Ron to believe in me and told him I’d create the program for free. He backed me up with his “show me what you got” attitude, on the condition the network reviewed all materials before airing.

During the contract negotiations, the phrasing and legal boilerplate stated the network wanted my soul, my blood, my firstborn child, and worldwide rights to everything associated with my show, forever. Somehow I was able to delay and argue and revise the contract long enough until they just gave up. As for turning in the finished tapes so they could review each episode before it aired, I was afraid the Connecticut crew (ESPN’s home base) would tinker with the tapes and muddle up my work, so my tactic was to turn in the tapes a day before show dates. If they hated something, they could cut the whole show or go with it untouched.

In one season, with

Kids in the Way

as my platform, I was able to change the way ESPN2 approached action sports.

The debut of

Kids

featured an interview in a laundromat with a band called Man or… Astro Man, who claimed they were messengers from outer space. I can’t imagine what the network heads were thinking when they saw the band jumping around in NASA jumpsuits, with the singer wearing a flaming TV set converted into a helmet while cavorting herky-jerky across the front of the stage. The only instance the network ever intervened and cut content from the show was an eight-second clip of fully clothed porn actress Jasmine St. Claire introducing a segment on Mike “Rooftop” Escamilla. I hadn’t expected the network guys to recognize Miss St. Claire, but there must have been some pervs in the standards and practices department.

Over the course of six episodes,

Kids

opened the door for shows like EXPN’s popular

X2Day

series, which is one of the most recognized features on the network today.

Kids

also helped expand the networks’ collective minds to recognize that music and action sports thrived on the same creative energy, and that through expression and artistry, our sports were about more than just a score; they were a way of life.

But my biggest reward for doing the

Kids in the Way

was getting to befriend one of the greatest living myths.

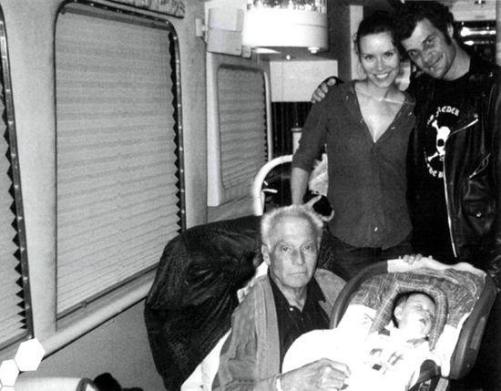

Evel came through town in his RV and invited us to dinner. This was three days after I slammed on my twenty-four-foot tall ramp and beat my previous world record. I’m pretty worked in this photo.

There is nobody in the world like Evel Knievel. His career as a motorcycle daredevil defies belief—that he had the skill and guts to pull off his stunts, using the equipment he employed. The other incredible part of his story is, of course, that he gave so much of himself and kept coming back, that he survived the falls he took. Evel is the original Never Back Down, Take No Shit superhero. An international icon and a man of solid principles, Evel’s legacy inspired me for many years. It was perhaps the ultimate reason for doing a TV show—so I could figure out a way sit down and talk to the man.

I got word that Evel was going to be signing autographs at a boat show in Los Angeles, so I hit the road with a cameraman in tow with the hopes of securing a legendary interview for

Kids in the Way

. I’d prepared and overprepared, and by the time I got to the boat show I was jittering with nerves. Just approaching Evel was not easy. He can be a hard bastard, mainly because he’s earned the right to command respect from his fans and the media. I stepped to him as a little bit of both. He was sitting at a table signing pictures when I approached and asked for a minute of his time. That’s about what I got, sixty seconds. It didn’t go well.

Evel had already been signing things and sitting there for a while and was getting tired and testy. His terse answers took me off guard. I don’t know what I expected, but I quickly learned nothing can prepare you for the Evel experience. He lives so

in

the moment, there are two ways he approaches any situation: He’s either superstoked or superpissed. There is no in between.

His business manager suggested we cut things short, and Evel shut us down and made his exit. I was so bummed; I’d flubbed up the chance to talk to one of the few guys in the world I really respected and with whom I felt a connection. Wandering around the trade show floor, I half-heartedly checked out jet skis and fishing boats, then drifted toward the lobby. Time to go. As luck would have it, I bumped into Evel. Without the camera present, I had a more casual convo with him, and he began to open up to me a little. I knew his history included a long list of line extensions (Evel grossed over $30 million dollars at his peak in the 1970s], so I was curious about his involvement with bikes. Evel had licensed his name to mass merchant companies to create entry-level BMX-style bikes in the past, and I asked if he’d ever considered doing a high-end, collectable signature bike, with top-of-the-line components. I mentioned I had a bike company and gave him my card before we parted ways. I returned to Oklahoma City, rejected but somehow enlightened.

Not long after, I got a phone call. A familiar, salty voice said, “Mat, it’s Evel. I’m going to Vegas to watch my son Robbie jump and break the world record. You want to come?” Not the kind of question I needed to be asked twice. I was on a plane immediately and spent three days in Sin City with the guy whose name was synonymous with the fountain at Caesar’s Palace, among other locations. We watched Robbie rocket into the record books, we gambled, and we drove around. At one point I was sitting in the backseat while Evel and one of his lifelong friends—his getaway driver—cruised through town reminiscing about back in the day. It was surreal, hearing the stories I’d read about for years, from the guys who’d lived it. The weekend was like a gift.

Together, Evel and I designed a couple of Evel signature bikes, which Hoffman Bikes released to commemorate historical stunts. I went to his wedding. Sometimes I get phone calls at two in the morning, and it’s Evel…just calling to shoot the shit or tell me he busted a rib. He pitches me his inventions, which I am not at liberty to discuss, but I can tell you they’re totally insane and amazing.

Because I was a “Kid” who’d figured out a “Way,” my dream to meet and interview Evel turned into reality. Then it kept progressing into something even better, friendship. It’s so weird, being friends with one of your idols. But it’s good-weird. I think the reason Evel and I hit it off so well is because we share the same wavelength—we know what it’s like to sacrifice and take pain and risks to experience the pleasures and success in life. Although he’s over sixty years old, Evel is as wild and hyped up as any twenty-five-year-old.

I can only hope that when I’m pushing sixty, I’ve got that kind of legacy to look back on, and that pure energy to propel me forward to whatever challenges the day brings.

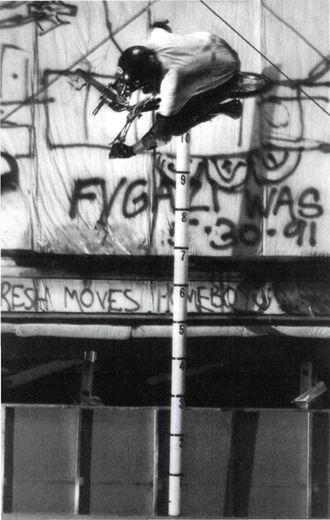

Steve Swope airing over the tag Fugazi left on the Secret Ninja ramp when they visited in 1991.

GROWING PAINS

Things began to stabilize at Hoffman Bikes after our first couple of years in business, but there was never a shortage of crisis situations. We were constantly strapped for cash and pushing to grow, but sometimes my team riders grew faster than we could as a company. While Jay Miron rode for Hoffman Bikes he got good—supergood. There were casual practice sessions at the Ninja Ramp and at the ramp park outside the warehouse that were no holds barred, some of the craziest shit I’ve ever seen done on bicycles. The top three spots at contests usually became a battle between Dave Mirra (our other HB star), Jay, and myself. Jay’s bag of tricks included Mironized no-footed 540s, a tailwhip air where he’d kick his legs into a superman, and total coping control with a slew of sick lip tricks. His surgical style of front- and back-brake-based bedlam helped popularize new ways of using the entire ramp—from the decks to the side railing. Jay constantly pushed the limits of his riding, and he was anxious to get some pay-back

for all his efforts. The most I could do was offer a modest salary and line up as many Sprocket Jockeys shows as possible, keeping our team busy on the road getting paid at fairs. Jay was annoyed, I think, because of our loose game plan. He wanted stability and a sponsor that had everything figured out—not the fly-by-night style Steve and I utilized during our entry in business, as we learned the ropes.