The Ride of My Life (34 page)

We didn’t know it, but all of the factory-sponsored pros we idolized were regular guys who rode bikes, just like us. Yeah, they were skilled at their craft, but outside the narrow world of BMX and freestyle, few knew who they were. The early promoters understood that the sport needed superstars, and using mostly smoke and mirrors, created the hype required to launch a whole category of bike riding. The recipe was simple:

more hype + more exposure + more kids into bikes = more money pumped into the industry

.

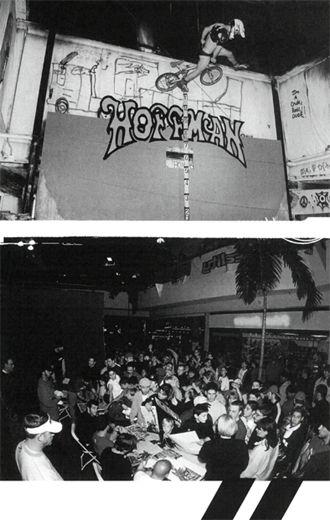

Clocking airs covered by nothing but Speedos and shoulder brace for an early Hoffman Bikes ad. The readership of Ride magazine were repulsed, and I found out the concept that “sex sells” doesn’t work in the bicycle industry.

A postdemo autograph session at the Crossroads Mall in Oklahoma City. This was the first time I had done a show in my home town in ten years. The mob was so big, it was more dangerous signing than it was riding.

For about a decade that formula worked like a charm. Then the bike industry cannibalized itself and unceremoniously collapsed.

During the early 1990s, after the industry bottomed out, freestyle was left for dead. A handful of people—riders, mostly—picked up the pieces and continued pushing the sport onward. During the lean years, a new generation of rider-owned companies was born. At first, they all had the same thing in common: They were run by idiots (myself included). One of the more memorable early Hoffman Bikes ads was

Sex Sells

. Under that blazing headline was a full-page photo of me blasting an Indian air wearing nothing but shiny black latex Speedos and a shoulder brace. Not sure how many bikes that one sold. But the most we could hope to do was entertain ourselves, have fun, and create the products and events we needed to thrive. At one time it was possible to go to a bike event and literally know every single person there—riders and crowd—by their first name.

Like other indie manufacturers, Hoffman Bikes learned the business as we went along. We only really knew one thing: We loved riding. What we lacked in financial firepower, we made up for in authenticity and passion. Nobody was there to get rich or famous, but there was a sense of shared vision fueling it all: Live to ride, ride to live. This seemed like a pretty good principle for a new foundation.

At the closing of the last BS contest of 1995, I got on the PA system and looked out at my friends in the crowd. I had a prediction I wanted to share. “This is the end of an era. Next year’s contest series is the start of a new one, and stunt riding is going to be huge. Our sport is going to grow like crazy.” ESPN2 had become part of the scene, like it or not, and bike stunt riding was primed to erupt for the second time in its short life. My biggest concern was how to maintain some control over the direction of the explosion. The steroid injection of mainstream media coverage had created a beast called “extreme sports,” and there were now “extreme lifestyle products” that had little to do with skateboarding, bike riding, or snowboarding. Automakers, soda companies, and makers of snack foods and personal hygiene products were all looking to get (insert electric guitar whammy bar sound here)

extreme!

For about five minutes, I was worried I’d be labeled a corporate sellout by a jury of my peers for joining forces with ESPN. The unwritten rule was you can’t make money off your art. But I’ve never been much for rules. I

knew

I wasn’t into bike riding for the money—if that were the case, I’d have bailed on the sport when it went broke back in 1990. With a new boom in our midst, the renaissance was happening

with or without our input. I didn’t want my integrity compromised when some bean counter with power started calling the shots. Bike riding is raw creative energy. For the rest of the world to understand it, and see it in the truest light, it needed a translator. That’s one of the reasons why I learned to make bikes, run contests, organize demos, and create TV shows. What I do is too important to me to let someone else who doesn’t know me interpret my life to the world. My philosophy is if you stay true to why you do what you do, then there’s is a huge difference between selling out, and everybody else buying in.

At first, some riders were apprehensive about TV and corporate sponsors, because they didn’t really understand what they were getting out of it. The irony was that the sport is a subculture created by free expression, and riding relies on one’s ability to adapt to new surroundings. Outsider interest in the sport was definitely a new environment for most of us. I tried to use humor to shake up both the bike riders and the network a little. At the first BS/ESPN contest I put on, we designed the victory plaques to feature riders in corporate attire, and money swirling through the air. I bought suits for all my event staff. I gave everybody on the crew twenty dollars in singles and instructed them to randomly tip people, “just for showing up.” By exaggerating their worst fears, I was able to get some of the hardcore bikers to loosen up and laugh. And I also wanted to make sure the network understood who we were, and what they were dealing with. That was the challenge I had taken on—mediating between two wildly different cultures that were popularizing action sports. Both sides had their own agendas, and each side could help the other, if they worked together. I knew the corporate side was guided by an entirely different set of principles. Often their viewpoint clashed with ours, but in their own stubborn ways, they could be a lot like us, too.

Not long after I started working with ESPN, I was running a contest that was off the hook—there were thousands of people in the stands, hundreds of bikers there, and the riding was great. Everybody seemed to be having a pretty good time. During the street event, one of my favorite riders, Jimmy Levan, saw a unique line nobody else had thought of—which consisted of a ramp transfer over a fence out of the contest area into the management area. As Jimmy was setting up for it, the X Games management freaked out. But Jimmy was used to dealing with people unable to understand his actions, and he jumped the fence anyway. He had to dodge the security and management guys who were totally in a tizzy over what he was trying to do when they realized, in terror, what he was setting up for. Jimmy launched the gap and cleared the fence, and the crowd went nuts. Instantly I was surrounded by flustered security and purple-faced management. Everybody was yelling at me, asking me why I wasn’t disqualifying that rule-breaking bastard [sorry, Jimmy], saying things like, “that behavior is not tolerated.” I had to chuckle, which made everybody even more pissed. The big wigs were blowing

their collective stacks because insurance only covered riders

in

the fenced-off area, and if somebody had gotten hurt, the whole event, the whole series, the whole extreme world would be shut down. As this flagrant insurance infringement was explained to me, additional network people joined the fracas and added to the disarray. They didn’t understanding how I could condone such an outrageous no-no in their world. I had to point out to them that Jimmy came from a different environment than theirs. They wanted to brand the guy an outlaw, but he’d done exactly what he would have if he were in his natural environment. The whole essence of street riding is to search out hard-to-find lines and create something out of nothing, to show others your unique approach to obstacles. “I understand your side of the story, that it wasn’t kosher in this simulated environment,” I said to the steaming promoters. “But this guy doesn’t operate in the same boundaries as you do. His very goal is to show you ways

around

the boundaries.” I also pointed out the mixed message they were sending us by freaking out over how bad it was, while their cameramen were setting up for the shot in the background.

I think both sides learned a bit about each other that day.

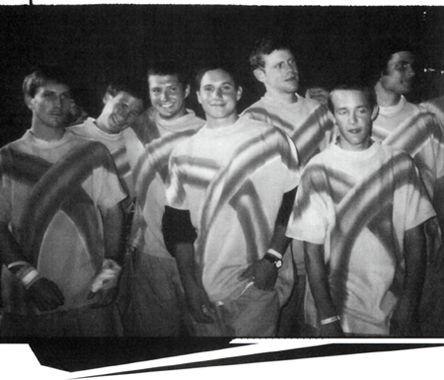

I was asked to put a team together for the closing ceremony of the 1996 Olympics. The ceremony was called Sport as Art. It was a great opportunity to put the best of the best together for a live audience of eighty thousand people, and a televised audience of tens of millions. It was a fun show. I did a no-handed 540 over Dave tailwhipping. None of the team was that stoked on the shirts they made us wear, though (left to right): Dennis McCoy, John Parker, Steve Swope, Dave Mirra, Taj Mahelich (obscured by Steve’s “heavy metal” sign), Rick Thorne, and me.

As Jaci was watching me talk to her on live TV, she noticed there was a two-second delay. I told the ESPN techs they needed to get that fixed. They didn’t find it humorous.

Jimmy Levan wasn’t the only rider to raise the hackles on the neck of authority during a televised event. I got in trouble once for treating the live TV feed from the X Games as my personal novelty item. It was in Rhode Island. We were broadcasting via satellite to twenty million people. I’d broken my foot practicing on the street course the day before and needed to take a one-day break if I was going to enter in vert. I rigged my shoe to work as a cast and helped Steve and the promotional team with running the event. I was spending the afternoon generally wandering the contest course tripping out on how insane bike riding had become but soon found a job to do: I was the starter for the dirt jumpers. I stood next to each competitor atop the starting concourse, and it was my job to give each guy their cues when to begin their run. While on the starting area, I noticed my head looming on the Jumbotron television. The camera guys were getting intro shots of the jumpers as they rolled in, and since the riders were looking at me to begin, I was in every shot. I Motorola-ed my wife. “Jaci, quick, turn on the TV.” The camera stayed on me as I told Jaci about how the day was going, laughing about what we were doing. She was listening to my voice and watching me talk and wave to her on TV back in Oklahoma. “Your hair’s messed up,” she pointed out over the phone. I fixed it. We continued talking, smiling and waving, and had a nice chat thanks to the hijacked airtime. It wasn’t until after the contest was over and they reviewed the tapes that the guys from the network saw what I was up to, but by then it was too late. Afterward, the network told me, ah, not to do that anymore, but they gave me a copy of the tape as a keepsake.

As the extreme coverage of the sport grew, the cultural shift kicked in. Alternative sports, action sports, extreme sports, hybrid sports… there were many names for what we did, and they were all becoming household terms. Soccer moms were putting bike racks on the minivans, and public ramp parks were getting as common as basketball courts.

USA

Today

reported that skateboarding was more popular than Little League baseball. And bikes had the highest ratings during the X Games.

The bike industry sales swelled from the effects of millions of kids exposed to stunt riding. As a recruiting system, the contest coverage was working well. Kids would see the X Games on TV and entry-level bike sales would skyrocket in the weeks before and after the contests. And distribution shifted around, too. The mom-and-pop bike shops were still the source for the hardcore equipment, but sporting goods stores and big box bonanzas like Wal-Mart and Costco were selling hundreds of thousands of bikes with their “buy it low, stack it high, sell it cheap” tactics.