The Ride of My Life (36 page)

In Zurich, Switzerland, I helped put on an event called The Freestyle.ch. This trip marked my introduction to photo radar traffic cameras. Our host, Reni, was driving me and few riders around and I spotted the traffic surveillance cams hovering over intersections. “What the heck are those things?” I asked. When I found out they were there to take pictures of drivers, I was amazed and wanted to see one in action. Before the end of the day we’d done a “photo session” around the city, running red lights on purpose and hanging out of the car, posing in the intersections, or crashing through with faces pressed up against the windshield. It was fun, but I never considered what would happen to our poor host three weeks later when the barrage of tickets arrived in the mail—she lost her license for a year. Sorry, Reni.

Sometimes, you fuck the rules. And occasionally, the rules fuck you.

We were running a BS contests in Portland, Oregon. Simon Tabron had come over from England and was giving the pro vert class a reason to believe he was going to win the contest—Simon was going to town and, as usual, looking smooth as glass. Then came the 900 attempt. Simon took a bad spill and got knocked out. The danger in getting knocked out comes when you start repeating the process. I’ve seen bike riders tempt fate (and done it myself) many times—after a bad slam they hop back on their bike and try to pull the trick before it puts them down for the day. Which is what Simon did when he came around. Mounting his bike, it was clear that Simon wanted to try another 9. As the organizer, everybody began telling me not to let Simon ride anymore. But I couldn’t make up a rule midway through a contest, a decision that could cost Simon $4,000. That would have to be his choice. I told Simon he probably shouldn’t be riding because of the KO, but I was leaving it up to him. He dropped in and crashed another 900, got up, and tried it one more time. He pulled it.

Immediately thereafter, all the pros were notified of the Tabron rule: If a rider got knocked out and had trouble recognizing what was happening around them after a slam, they were done for the day.

At the next X Games, Kevin Robinson crashed a no-handed 5 that left him on his back in the flatbottom, in an eyelid-fluttering slack-jawed daze. It was scary. Suddenly his eyes popped open, and his mouth started jabbering a mile a minute, “Mat, Mat, I can do this. Let me do this.” He’d been out for a minute, and the Tabron rule was in effect. I sighed. “Kevin, I hate to do this to you, but… I’m gonna call the Tabron rule on you.” He was bummed. But at least I knew he’d still have his marbles at the end of the day.

A week later there was a demo disguised as a pro contest in Japan. The pro class of Kevin, Dave Mirra, and I were about to drop in and ride. Suddenly the arena went into a blackout. We were up on the decks wondering what happened when the house lights blazed to life, and in the flatbottom of the ramp there was a full squad of Japanese schoolgirls in Western cheerleader outfits. The PA system began crunching out X’s version

of “Wild Thing.” The cheerleaders bopped around, shaking pom-poms. Up on the deck, all the pros exchanged confused, amused, “Did you know about this?” looks with each other. After a couple minutes of foreplay, the ramp was cleared, the Japanese fans had been thoroughly stoked up, and we were ready to get busy I dropped in, and during one of my runs I went for a rocket barspin, back to a bar-spin, to a late no-footer. The thing about Japanese crowds is they all come strapped with the latest technology. In this case, everyone had a point and shoot camera with compact flash. In midair, with my handlebars spinning and my feet on the back pegs, thousands of camera flashes lit up the arena in a crazy strobe effect. My chrome handlebars flared and stuttered through a spin. As I reached for my grips, I thought I got them, and then…

There was an Asian man grinning at me through the view out the front of my helmet…

Hey, why was I wearing a helmet? Why was there a bike next to me? How did I get in front of four thousand Japanese people, and why are they all clapping at me?

In one ear, a medic was asking me questions in Japanese.

Huh?

Someone who spoke English nudged the medic out of the way and began asking me what my name was, over and over. At the same time, another English speaker popped up on the other side of me, saying,

Mat, Mat, Mat, How are you Mat?

I was still baffled how I got there, what happened, what my connection was to these people, and why I just woke up on the bottom of a bike ramp. They said I was out for three minutes, but I had no recollection of any of it. Then, without warning, snap. My memory flooded back all at once, and I was a little shocked—it never went from totally blank to good as new, but hell, I wasn’t even hurt. I had energy, and my balance was fine. I’d only crashed on my fifth wall. I could still finish my run. I went for my bike. Kevin Robinson tapped me on the shoulder. “Mat, I hate to do it to you, but I’m gonna call the Tabron rule on you.” Damn!

I ended up winning $2000 anyway, and they paid me in cash. After the contest, I accidentally left the entire wad of bills sitting in a restaurant and didn’t realize it until the next day. I called back and asked if they’d, uh, found a big stack of cash lying around. The manager had been expecting my call. I got her a gift certificate to her favorite sushi bar as thanks.

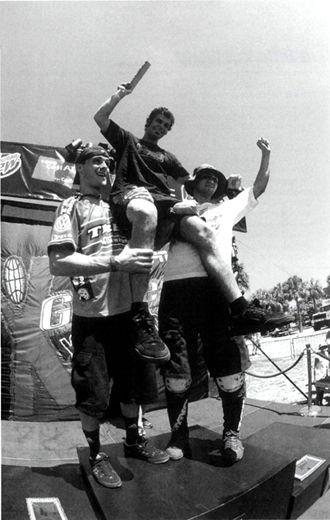

2000 was an insane year. I never thought I’d make it back on top of a podium again after my knee injuries.

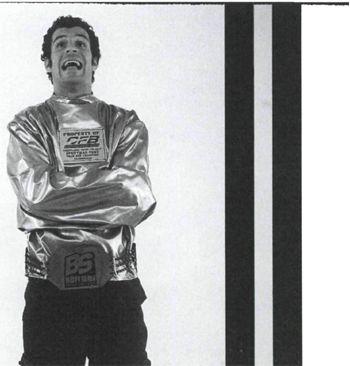

The best part about running the comps is you get to choose the prizes The CFB Golden Straight Jacket Series award.

I can’t pick out and describe my best run of all time. In contests, I don’t plan out what I’m going to do; I just drop in and go, and let the run happen. When it’s over, I’m already forgetting what I did as I clear my head for my next run. I can say for certain that my best run ever was not in a contest. At a comp, the window in which you’re judged is two one-minute runs during the course of a whole weekend—sometimes the skills flow effortlessly; other times it seems like the whole world is against you.

For a long time, I won most of the contests I’d entered. It was rewarding in some ways, but then again, winning all the time is boring. You lose your motivation, because you don’t get pushed enough. You realize you can never get better than winning. That’s why I loved losing. It inspired me to push myself harder and progress.

As the X Games era exposed the sport to millions of kids, and the equipment and riding facilities got better, I watched a new breed of pros come into the sport, trickling up from the amateur ranks. Raised on resi mats and foam pits, their precision skills were a product of the solid ramps and superfacilities like Woodward BMX Camp in Pennsylvania. The new guys were smooth, their runs usually planned and tight. And for the first time in my life, I didn’t care if I could test myself against the best riders in the sport. All I wanted was to ride again, on my own terms. My biggest competition became my health.

Even though Steve and I were in charge of running the biggest contest series in the sport, it felt like the scene was getting jacked around quite a bit. The BS contests of the early 1990s had been absorbed by ESPN and become the gateway to the X Games, and everything in the sport was focused on that once a year event. The X Games were centered around television, which had permeated our culture and become a huge force in the sport. To their credit, the ESPN crew had evolved into a great group of guys who were dedicated to the sport and respected the riders as equals to any athletes on the network. Another upside was the prize money was getting pretty big, but the bottom line was, the contests were a zoo: fans, crowds, parking, passes, photographers, interviews—the last thing on your mind at a contest was actually riding.

Steve came up with the idea to hold a biker-run, biker-produced, biker-officiated series like back in the days before TV. We worked out a deal with Ron Semiao to create a structure that benefited everybody: We would still hold comps that would provide a buildup to the X Games, but the new contest series was centered around riders, not TV. When we came up with the name BS series in 1992, we’d joked about how funny it would be if the contests ever got on television. After we realized it was possible to get strait-laced sportscasters talking about BS on TV, it became our Holy Grail to think of a way to elevate the level of televised profanity. I proposed calling our new contests the Crazy Fuckin’ Bikers Series. Soon after, I worked out the deal to produce the TV for the contests and knew there was no way we could get away with the word

fuckin’

on ESPN. The title was abbreviated to CFB, and we vowed that if anybody from the network ever asked, we’d tell them the F-word in the initials stood for

freakin’

. But strangely, nobody ever asked. The first day of our first CFB comp in Merritt Island, Florida, I got a call from Ron. He’d heard a rumor. “Mat, I just want to let you know, we have rules. Rule number one is, you’re never allowed to use the word

freakin’

on ESPN networks. Rule number two is, you’re never allowed to use the word

freakin’

on ESPN networks. And rule number three: Always obey rules one and two….” I’d already written and recorded the theme song for the show. All around me at the contest were banners blaring the words

Crazy Freakin’ Bikers

. “Hmmm, Ron. I think it may be too late.”

We rode in it, hosted it, judged it, documented it, and after it was done, made a TV show about it. Rather than show the top three riders’ runs in a blow-by-blow format, we tried a more relaxed coverage format. There was a lot of humor, and montages of the top riders’ best tricks from the day, plus candid footage to give viewers a sense of a rider’s character in addition to their strengths, style, and skills. Above all, the approach was very noninvasive. At the end of the contest, we’d have a session in the edit bay, then hand ESPN a tape and they could put it on the air. It was a way we, the riders, could translate our sport for the masses so people could see it through our eyes, instead of watching some random television producer’s take on it. Luckily, the content

proved to be more valuable than the controversial title, and every show of the series aired. The end of the year award for the CFB would be something special—the BS series awards had always been giant belts, like the ones awarded to prizefighters. Hoping to top the goofy glory somehow for year-end honors, we came up with the CFB Golden Straitjacket award.

In 2000 and heading into 2001, I had an opening in my career where I took nothing for granted. Riding had progressed so much. I wondered if I’d progressed with it. While I was out being injured, the sport had gotten good. Double tailwhips, 540 tailwhips, high flairs, 900s, and more were the stuff one needed to throw down to win a modern pro contest. I started to get back my tricks one by one, like flairs and double tailwhips, and I came up with a few new ones like peg grab 540s and no-hand, one-foot 540s. Without brakes, my lip trick abilities were limited, but if I could maintain my aerial bombing runs at high altitude, peppered with double and triple variations, maybe I had a shot.

When I started getting solid again, I gained a new respect and a stronger love for what I could do with my bike. I cherished the moment I was able to ride at pro caliber. 2001 was a year of celebration, full of the

I’m riding!

type of joy that interested me in the first place. I entered a few contests for fun, concentrating on flow, not a set routine with a preplanned array of tricks. By the end of the 2001 season, I’d won my eighth BS contest series belt, my tenth World Championship title, and the first CFB Golden Straitjacket award. I was stoked. I’d done what I wanted to do.

The Philly X Games in 2001 would be my last big-time contest. With a full pro class going for $63,350 in prize money, the competition was fierce. Jay Miron, Dave Mirra, Dennis McCoy, Jamie Bestwick, Simon Tabron, Kevin Robinson, and I scrapped it out. Dave won, Jay came in second, I got third. I was happy. I’d ridden my heart out, and I pulled a 900—the first one I’d made since 1994. But after over seventeen years of staying in the mix on the contest scene, I just decided to step back. I didn’t make a big deal about it, but I mentioned to a few people that I wasn’t planning on hitting the circuit to chase a title or riding in the X Games in 2002.