The Ride of My Life (44 page)

Aside from the dozens of roadies, production coordinators, and technicians, the success of Vegas rested on the shoulders of the talent pool. Social Distortion and The Offspring would provide sonic support from the stage. Tony, Andy MacDonald, Bucky

Lasek, Bob Burnquist, Lincoln Ueda, and Shawn White were the skating contingent. Dave Mirra, Dennis McCoy, John Parker, Kevin Robinson, and I represented bikes. On the motocross tip, Mike Cinqmars, Cary Hart, Dustin Miller, and old school super-cross champ Mickey Dymond (subbing for the Clifford “The Flyin’ Hawaiian” Adopante, who totaled himself in practice). Everybody had their own unique skills, and we were all focused on one job: Go huge.

Our group spent eleven hours a day inside the airplane hangar, tightening up the show routine, getting accustomed to the ramp, and figuring out our collective cues and timing. It was hairy—if one person was off by a second, it threw everybody into confusion and chaos. There were a couple collisions, and some very close calls. Most of the time, bikes have an advantage when riding with skaters because with a couple extra pumps, we can increase our altitude and air over them—but Lincoln Ueda made that impossible, because he was comfortably clocking twelve footers. He’s like Sergie Ventura, Danny Way, or vintage Christian Hosoi—unstoppable. The skaters were also doing an insane freight-train-style run where they’d all drop in and work the ramp from end to end, practically touching boards the entire time. The FMX guys would circle the ramp like sharks, and gun it for the attack, throwing their machines high overhead two at a time and whipping off everything from handstands (Hart attack airs) to stretched bar hops, nothings, Indian airs, and more. It gave me chills just watching them skying directly above us on the ramps, like supersonic jets doing deck top flybys.

During our daily meetings we’d brainstorm our runs, and all the other riders and skaters decided Tony and I were going to end the show with a finale—side-by-side 9s. I’ve never tried to plan a 900 in a run. Ever. They either happen or they don’t, depending on if I felt the spin inside me that moment. “Tony, are you consistent with 900s?” I asked him. He shrugged, gave a nervous chuckle, and rubbed a phantom hip pain, which let me know the same rules applied to a 900 on a skateboard—it’s not a trick you can predict or control. You just throw. What were the odds we’d both pull them at the same time? Vegas was the perfect town to find out.

TESTIMONIAL

TOUR OBSERVATIONS

Mat and I have done a few demos together over the years. In that time, I have seen him dislocate his shoulder twice, get knocked out, dislocate his knee, break his wrist and hit a ramp harder than anyone in the history of our sports. In almost every instance, he managed to get up and ride the next day. I realized he was truly committed (aka crazy) when he tried to tape his broken wrist to his handlebars in order to finish out our 2001 Gigantic Skatepark Tour.

-TONY HAWK, PRO SKATEBOARDER

Vegas is a city that’s all about moving money around. It’s a place to take risks, an oasis of entertainment for just about any taste. It’s also the most extreme town in the USA—this was clear as I took a walk down the strip. Overhead, blaring billboards bombarded Sin City patrons with promises of loose slots, huge steaks, magic tigers, chattering dolphin shows, and the raunchy comedy of Mr. Jingles, the world’s coarsest clown. Suddenly an animated rooftop sign lit up: TOMORROW NIGHT: TONY HAWK’S BOOM BOOM HUCKJAM. No turning back—we were part of the nonstop entertainment stream. There were eight thousand seats in the events center. Our goal was to fill the house, then rock it. If we could pull a grand slam in Vegas, it meant the HuckJam was certified for touring.

Our weeks of practice had paid off and the show was dialed—everything was tight, except for the last trick. We hadn’t dared spend 9’s in practice. I was already pushing the limits just to keep myself in the show. I’d separated a rib from my sternum taking a slam, and my wrist was worthless without gobs of tape. My body had totally exceeded the “ice, aloe, and TLC” treatment regimen prescribed by Tony’s head trainer Barry Zaritzky so I went to a local doctor and told him I needed anti-inflammatory medicine to bring the swelling down and loosen up my torso. With years of self-diagnosing my body, I knew just what I’d done and how to fix it. The emergency room doctor I saw was skeptical—he wanted a battery of tests to check everything from my heart rhythms to my bone structure. I pulled out a list of surgeries and injury descriptions, which Dr. Yates had written and showed it to the doc. “See, I do this all the time,” I told him. He nodded, canceled the tests, and scribbled a prescription for the medication to put me back in the game.

Sitting at the blackjack table in our hotel casino a few hours later, I was still sore and needed to chill and get my mind to relax. A few rounds of cards would do the trick. The dealer began pestering the players at the table and picking on me in particular with snarky remarks every time I won—I was up $250 at a five-dollar table. The dealer’s cracks were annoying, but who was I to disrupt my own winning streak by moving to another table? I stayed in a few more hands, until finally some lady at the end of the table began yelling at me. “Hey, Bucko!” she screamed. I tried ignoring her. “Bucko! Bucko! Look at me.” It blew my concentration, and between this rude lady and the rude dealer I wasn’t having much fun anymore. “Screw this, you guys are jerks. And, lady, quit calling me Bucko,” I glared at her. She gave me a puzzled look. “I was talking to my friend standing right behind you, whose name happens to be Bucko,” she spat back. I turned around and there was a Vegas bride in full gown, drinking a Budweiser. Mrs. Bucko, I presumed. It was time to get some sleep. Tomorrow would be a big day.

A DJ had primed the crowd on the ones and twos, filling in the air with beats and setting the mood for some fun. The arena faded to pitch black, and the buzz of the crowd turned to a roar. The house was filled with people anxious to see just what a HuckJam looked like. The lighting rig covered the entire ceiling [“more lights than Metallica’s show” one veteran roadie told me]. A huge curtain fell away revealing the ramp, cast in shadows. As the MC introduced each athlete a spotlight illuminated us, one by one. Then it was time to get it on. The BMX section was first, and all the lights flipped on to the opening drum kicks of “Paranoid” by Black Sabbath. Suddenly Kevin Robinson was upside down throwing a corkscrew over the huge channel. Dave Mirra sailed through the air spinning ridiculously high tailwhips, and airing both directions. Dennis cracked can-cans and 5s. John Parker gave up giant alley-ooping variations and looked smooth as grease. Then it was my turn. I pedaled across the deck and dove into the first wall with a ten-foot no-hander, spreading my wings and holding it stretched as the MC told the crowd the Condor was in the house. It felt great.

The HuckJam was divided into segments of BMX, skate, and FMX, then Social Distortion took the stage. During the band, we all rode in a jam format and watched the music from the best seat in the house—on the decks of the ramp. After Social D finished a twenty-minute set, the skaters and bikers did the gap jump down the giant roll-in, and then it was time for The Offspring to bring the noise. The whole time, the crowd was great—freaking out, standing up, and getting loud.

Finally, it was time for the finale. Time to put the Boom Boom into the room. Mike Ness from Social Distortion came back out with The Offspring and they ripped into a blazing cover of The Ramones’ “Blitzkrieg Bop.” As the opening riff kicked in and “Hey! Ho! Let’s Go!” came out of the speakers, the energy in the building went into overdrive. Every single athlete was on the ramp at once—giant TNT bombs thundered to life, courtesy of the pyro expert, and shook the roof. Mike Cinqmars flew fifty feet overhead with his motorcycle completely kicked out sideways, and on the opposite side Cary Hart blasted past in a full Hart attack handstand. On the ramp, Dave was throwing eight-foot carving tailwhips over the channel with Bucky 540ing underneath, followed by Bob cleaning up with sizzling one-footed Smith grinds. The opposite wall was just as busy—I flaired next to Kevin as he pulled a flair, with Shawn and Tony spinning 360s and tail-slides right behind us. It was three minutes of totally precise insanity. The whole arena was on their feet, shouting the chorus as one big voice, as we unleashed every trick we could.

Every trick, that is, but one. At the end of the mad jam, the song stopped and the crowd exploded with appreciation. We all took a bow, savoring the moment. The MC said there was one last bit to the show, and that Tony and I were the two originators of the hardest trick in the book. In seconds, eight thousand people were all chanting in unison, “Nine … nine … nine…” I looked over at Tony, who shrugged happily, but intensely. We dropped in and pumped a couple feeler airs until it was right. We both left the coping spinning and … came up with snake eyes. I touched down on my wheels and slid out into the opposite wall. Tony took a hard one to the tailbone.

But in the end it didn’t matter. The show was amazing, and all the pressure about pulling one trick didn’t seem to matter to the crowd. We’d just taken action sports to a new place, as individuals and as a group. The creative energy of music, art, and sport had been fused together and was powerful enough to fill a giant room.

It was long way from the days of sessioning a backyard ramp with a couple friends on the deck and a boom box blaring Black Flag.

Or was it?

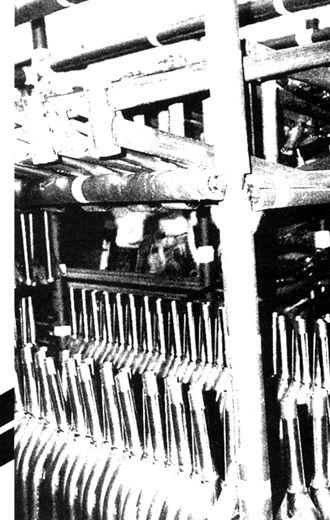

Hoffman Manufacturing. A shoestring operating budget kept a steady supply of frames, forks, handlebars, and more flowing out the door. This batch is ready to get a paint job.

TRICK ROLODEX

The coolest thing about bike riding is that it’s a sport that can be turned into an art. Fearlessness and balance will get you far, but creativity is king. Even when I’m not riding, my brain is at work trying to think up new ways to twist an aerial or throw my limbs.

I go through spurts of enjoying different tricks. Riding with good friends is a great way to learn new stuff. So is shooting photos, if you have a good relationship with a photographer you trust. They make you want to push your limits and ponder the question every bike rider asks themselves: What else can I do?

BARHOP

This was one of the last tricks I learned on my backyard halfpipe, and I debuted it on the Haro tour in 1988. I’ve never had them more dialed than the time I shot

Aggroman

and the

Ride On

with Eddie Roman. Size twelve feet make this especially hard for me. Barhops have been adapted by FMX riders to great success.

A one-handed barhop air. As you jump over the bars with your feet, you’re controlling the bike with one hand, which is hard. You have to find a center of balance and stall, then steer and reenter while you get your legs back behind the handlebars.

This is a superman into a barhop. Your legs are at the furthest points they can possibly be on the bike—stretched behind you and then jabbed over your front tire. The only other person I’ve even seen try barhops in a long time is Leigh Ramsdell.

A can-can lookback to candybar. Your body has to be all the way in front of your bike with your back facing the ground to tweak the can-can lookback. Then you straighten out and throw a leg over the handlebars into a candybar and pull it back over the crossbar as you’re headed straight down into the transition. If you don’t make it, you’re a dead sailor.

My version of hip-hop sampling. The two songs in this beat include a one-footer one-hander on the bottomside, in tribute to skatepark great Mike Dominguez, and when I throw the topside one-hander, bottomside one-footer it’s a tribute to his greatest rival, Eddie Fiola. This is the only air I have named after other riders, both skatepark rulers.

In 1987 there was a poster hanging in the Edmond Bike shop of Tony Hawk doing an Airwalk. It got me inspired to think of what else I could do with my legs during an air. I was stretching cancans, and people were calling them Hoffmonian can-cans, so I decided to see if I could get my feet can-canned on opposite sides of the bike. This was one of the first tricks that put me on the map.

This is an Indian to topside no-footed can-can. You stretch from legs dangling below the bike, to legs flung upward on the opposite side. I’m constantly trying to find new balance points and stable places in different aerials, and see what I can build on them.

I originally thought up the name for an Indian air before I did the trick, and it turned out to be a slightly different configuration than what I had in mind. I called this version, where I started doing them with my legs crossed, sitting Indian style, the Indian air classic. It was around the same time Coke changed their recipe and the name of their product.