The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (65 page)

Read The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers Online

Authors: Paul Kennedy

Tags: #General, #History, #World, #Political Science

It was harder to attempt an answer to such questions in the case of a “closed” society like the Soviet Union. Nonetheless the outlines of Soviet economic growth and military power in that era now seem evident. The first and most obvious point was that Russia had been

dreadfully reduced in strength, more than any of the other Great Powers, by the 1914–1918 conflict and then by the revolution and civil war. Its population had plummeted from 171 million in 1914 to 132 million in 1921. The loss of Poland, Finland, and the Baltic states removed many of the country’s industrial plants, railways, and farms, and the prolonged fighting destroyed much that remained. The stupendous decline in manufacturing—down to 13 percent of its 1913 output by 1920—concealed the even greater collapse of certain key commodities: “thus only 1.6 percent of the prewar iron ore was being produced, 2.4 percent of the pig iron, 4.0 percent of the steel, and 5 percent of the cotton.”

126

Foreign trade had disappeared altogether, the gross yield of crops was less than half the prewar figure, and per capita national income declined by more than 60 percent to a truly horrendous level. However, since the extreme severity of these falls was chiefly caused by the social and political chaos of the years 1917–1921, it followed that the establishment of Soviet rule (or indeed

any

rule) was bound to effect a recovery of sorts. The prewar and wartime development of Russian industry had bequeathed to the Bolsheviks an array of factories, railway works, and steel mills. There was a basic infrastructure of railways, roads, and telegraph lines. There were industrial workers who could return to the factories once the civil war was over. And there was an established pattern of agricultural production, and the sale of foodstuffs to the towns and cities, which could be restored once Lenin had decided (under the New Economic Policy of 1921) to abandon the fruitless attempts to “communize” the peasantry and instead to permit individual farming. By 1926, therefore, agricultural output had returned to its prewar level, followed two years later by industrial output. The war and revolution had cost Russia thirteen years of economic growth, but it now stood ready to resume its upward surge.

But that “surge” was unlikely to be swift enough—certainly not to the increasingly autocratic Stalin—while Russia labored under its traditional economic weaknesses. With no foreign investment available, capital had somehow to be raised from domestic sources to finance the development of large-scale industry

and

the creation of substantial armed forces in a hostile world. Given the elimination of a middle class, which could either have been encouraged to create capital or plundered for its existing wealth; given, too, the fact that 78 percent of Russian population (1926) remained in a bottom-heavy agricultural sector, which was still overwhelmingly in private hands, there seemed to Stalin only one way for the state to raise money and simultaneously increase the switch from farming to industry: that is, by the collectivization of agriculture, forcing the peasants into communes, destroying the kulaks, controlling the output from the land, and fixing both the wages paid to farm workers and the (far higher) prices of food for resale. In a frighteningly draconian way, the state thus interposed itself

between rural producers and urban consumers, and extracted money from each to a degree that the czarist regime had never dared to do. This was accentuated by the deliberate price inflation, a variety of taxes and dues, and the pressures to show one’s loyalty by buying state bonds. The overall result, represented in the crude macroeconomic statistics, was that the share of Russian GNP devoted to private consumption, which in other countries going through the “takeoff” to industrialization was around 80 percent, was driven down to the appalling level of 51 or 52 percent.

127

There were two contrary, yet predictable economic consequences from this extraordinary attempt at a socialist “command economy.” The first was the catastrophic decline in Soviet agricultural production, as kulaks (and others) resisted the forced collectivization and then were eliminated. The horrific preemptive slaughter of farm animals—“the number of horses fell from 33.5 million in 1928 to 16.6 million in 1935; and the number of cattle from 70.5 to 38.4 million”

128

—in turn produced a staggering decline in meat and grain outputs and in an already miserable standard of living, not to be recovered until Khrushchev’s time. Esoteric calculations have been attempted as to the proportion of the national income which was later returned to agriculture in the form of tractors or electrification—as opposed to the amount siphoned off by collectivization and price controls

129

—but this is an arcane exercise for our purposes, since (for example) tractor factories, once established, were designed to be converted to the production of light tanks; peasants, of course, were not so useful in checking the Wehrmacht. What

was

incontrovertible was that for the moment, Soviet agricultural output collapsed. The casualties, especially during the 1933 famine, could be reckoned in millions of lives. When output began to recover in the late 1930s, it was expedited by hundreds of thousands of tractors, hordes of agricultural scientists, and armies of tightly controlled collectives. But the cost, in human terms, was immeasurable.

The second consequence was altogether brighter, at least for the purposes of Soviet economic-military power. Having driven private consumption’s share of the GNP down to a level probably unmatched in modern history—and certainly far lower than, say, the Nazis could ever contemplate in Germany—the USSR was able to deploy the fantastic proportion of around 25 percent of GNP for industrial investment and still possess considerable sums for education, science, and the armed services. While the workplace of much of the Russian people was being transformed at a staggering rate, with the number employed in agriculture dropping from 71 percent to 51 percent in the twelve years 1928–1940, that population was also being educated at an unprecedented pace. This was vital at two levels, since Russia had always suffered—in comparison, say, with Germany or the United

States—from having a poorly trained and illiterate industrial work force, and in possessing only a minuscule number of engineers, scientists, and managers necessary for the higher direction and

steady improvement

of the manufacturing sector. With millions of workers now being trained, either in factory schools or in technical colleges, and then (slightly later) with a vast expansion in university numbers, the country was at last acquiring the trained cadres necessary for sustained growth; the number of graduate engineers in the “national economy” rose, for example, from 47,000 in 1928 to 289,900 in 1941.

130

Many of the figures touted by Soviet propagandists in this period were doubtless inflated and concealed various weak points, but the deliberate allocation of resources to growth was unquestionable. So, too, was the creation of enormous new power plants, steelworks, and factories beyond the Urals, invulnerable to attack from either the West or Japan.

The resulting upturn in manufacturing output and national income—even if one accepts the more cautious estimates—was something unprecedented in the history of industrialization. Because the actual volume and value of output in earlier years (e.g., 1913, let alone 1920) was so low, the percentage changes are almost meaningless—even if

Table 28

above serves the useful point of showing how the USSR’s manufacturing production was expanding during the Great Depression. However, if one examines only the period of the two Five-Year Plans (1928 to 1937), Russian national income rose from 24.4 to 96.3 billion rubles, coal output increased from 35.4 to 128 million tons and steel production from 4 to 17.7 million tons, electricity output rose sevenfold, machine-tool figures over twentyfold, and tractors nearly fortyfold.

131

By the late 1930s, indeed, Russia’s industrial output had not only soared well past that of France, Japan, and Italy but had probably overtaken Britain’s as well.

132

Behind this impressive buildup, however, there still lurked many deficiencies. Although farm output slowly rose in the mid-1930s, Russian agriculture was now less capable than before of feeding the nation, let alone producing a surplus for export; and the yields per acre were still appallingly low. Despite fresh investment in railways, the communications system remained primitive and inadequate for the country’s growing needs. In many industries there was a heavy dependence upon foreign firms and foreign expertise, especially from the United States. The “gigantism” of the plants and of the entire manufacturing processes made difficult any swift adjustments of the product mix or the introduction of new designs. There were inevitable bottlenecks, too, because the planned expansion of certain industries did not match the existing stocks of raw materials or skilled manpower. After 1937, the reorientation of the Soviet economy toward a massive armament program was bound to affect industrial continuity and to distort the earlier planning. Above all, there were the great purges.

Whatever the reasons for Stalin’s manic, paranoid assault upon so many of his own people, the economic results were serious: “civil servants, managers, technicians, statisticians, even foremen”

133

were swept away into the camps, making Russia’s shortage of trained personnel more acute than ever. While the terror no doubt drove many to demonstrate a Stakhanovite loyalty to the system, it also greatly inhibited innovation, experimentation, open discussion, and constructive criticism: “the simplest thing to do was to avoid responsibility, to seek approval from one’s superior for any act, to obey mechanically any order received, regardless of local conditions.”

134

It saved one’s skin; but it did not help the growth of a complex economy.

Having been born out of a war, and feeling acutely threatened by potential enemies—Poland, Japan, Britain—the USSR devoted a large share of the state budget (12–16 percent) to defense expenditures for much of the 1920s. That share fell away during the early years of the first Five-Year Plan, by which time the regular Soviet armed forces had settled down to about 600,000 men, backed by a large but inefficient militia twice that size. The Manchurian crisis and Hitler’s accession to power led to swift increases in the size of the army, to 940,000 in 1934 and 1.3 million in 1935. With the rise in industrial output and national income deriving from the Five-Year Plans, large numbers of tanks and aircraft were built. Innovative officers around Tukhachevsky were willing to study (if not fully accept) ideas from Douhet, Fuller, Liddell Hart, Guderian, and other western theorists of warfare, and by the early 1930s the USSR possessed not only a tank army but also a large paratroop force. While the Soviet navy remained small and ineffective, a large aircraft industry was created in the late 1920s, which for a while produced more planes each year than all the other powers combined (see

Table 29

).

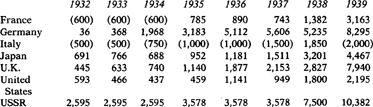

Table 29. Aircraft Production of the Powers, 1932–1939

135

But these figures, too, concealed alarming weaknesses. The predictable corollary of Russian “gigantism” was an excessive emphasis upon quantity. Given the attributes of a command economy, this had resulted in the production of enormous numbers of aircraft and tanks by the early 1930s; by 1932, indeed, the USSR was producing over 3,000

tanks and over 2,500 aircraft—fantastically more than any other country in the world. Given the tremendous growth of the regular army after 1934, it must have been extraordinarily difficult to find sufficient highly trained officers and NCOs to supervise the tank battalions and air squadrons. It was even more difficult, in a country with a surplus of peasants and desperately short of skilled workers, to man a modern army and air force; despite the massive educational program, the country’s chief weakness in the 1930s probably still lay in the poor training of many of its workers and soldiers. Furthermore, Russia, like France, was a victim of heavy investment in aircraft and tank types of the early 1930s. When the Spanish Civil War showed the limits, in speed, maneuverability, range, and toughness, of these first-generation weapons, the race to build faster aircraft and more powerful tanks was accelerated. But the Soviet arms industry, like a large vessel at sea, could not change course swiftly; and it seemed folly to stop production on existing types while newer models were being built and tested. (In this connection, it is interesting to note that “of the 24,000 Russian tanks operational in June 1941, only 967 were of a new design equivalent or superior to the German tanks of that time.”)

136

On top of this, there came the purges. The decapitation of the Red Army—90 percent of all generals and 80 percent of all colonels suffered in Stalin’s manic drive—not only had the overall effect of destroying so many trained officers, but had specific results which badly hurt the armed forces. By wiping out Tukhachevsky and the “modern warfare” enthusiasts, by eliminating those who studied German methods and British theories, the purges left the army in the hands of such politically safe but intellectually retarded figures as Voroshilov and Kuluk. One early result was the disbanding of the seven mechanized corps, a decision influenced by the argument that the Spanish Civil War had shown that tank formations could play no independent offensive role on the battlefield and that the vehicles should be distributed to rifle battalions in order to support the infantry. In much the same way it was decided that the TB-3 strategic bombers were of little use to the USSR.