The River at the Centre of the World (9 page)

Read The River at the Centre of the World Online

Authors: Simon Winchester

Tags: #China, #Yangtze River Region (China), #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #General, #Essays & Travelogues, #Travel, #Asia

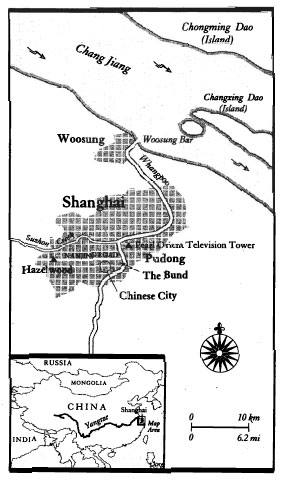

His card offered an impossibly long description: he was Master of the Woosung Supervision Station of the Shanghai Harbour Superintendency Administration of the People's Republic of China, Shanghai Bureau of Maritime Safety of the Superintendency of the Ministry of Communications. He gave me tea, showed me the Chinese charts of the Yangtze – stamped ‘Secret’ on every page – and then took me upstairs, to a darkened room at the top of the building. There was a double door, an air lock. Inside three men peered intently at a bank of colour computer screens and whispered occasionally into microphones.

‘These are the air-traffic controllers of the sea,’ said Mr Zhang, with a chortle. ‘They run the most up-to-date harbour control system in the world. It makes me very proud.’

The Germans supplied the computers, the Chinese made everything else themselves. Every one of the ships coming along the Lower Yangtze that day, and every single vessel turning into or out of the Whangpoo, was tracked on radar. Computers assessed all the tracks, the speeds and the directions, and calculated who might collide with whom, and what changes needed to be made to ensure they didn't. It was the operators' job to tell the skippers what the computers wanted. All of the operators were Chinese. One spoke English, another Greek, the third Russian, and they used these languages, and more often Chinese, to talk to the watch officers on the ships that passed below. Mr Chen, a man of about twenty-five who spoke impeccable English, was talking to an Indian bulk carrier, just now mooring at Baoshan. ‘Bringing coal up from Calcutta,’ he said. ‘Then coming to Shanghai to take – what is it? –wolfram and antimony ore, back to India. Typical. I have to watch him in and out. Make sure he doesn't hit anything.

‘The computers make it very easy. It really is like air-traffic control. Twelve hours on, twelve hours off. Very intense. But fine job, don't you agree?

‘This is bringing Shanghai into the next century, I think. Soon – not very long, I am sure – it will be the finest port in the world. It will pass Hong Kong, Singapore. This system is going to help. We will win! That I guarantee.’

Mr Zhang patted him on the shoulder, and ushered me out from the dark, and down the stairs. Soon I was stepping gingerly over the rotten fishheads on the dockside once again, this time making my way to what I hoped might be the Woosung railway station. I needed to get to Shanghai, and for purely historical reasons the train seemed the best bet.

For this was the third reason for Woosung's fame. This might now be the site of China's first computerized port; but a century and a quarter before, doubtless confirming Mr Zhang's view that his city had long been in the vanguard of China's modernization, Woosung was the site of the country's first, and as it happens very short-lived, steam railway.

It was Jardine, Matheson & Co. who built it. This is hardly surprising: the firm whose mercantile empire still remains a potent force in the Far East was instrumental – via such devices as railway making and shipbuilding – in opening up China to foreign commerce. (Its contacts back in London were such as to influence governments: it is still said today, and not entirely unfairly, that the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston, suggested the prosecution of the First Opium War – with the cession of Hong Kong the most notable corollary to Britain's military success – mainly to keep the Jardines opium trade in business.) But the construction of this first modest permanent way over the twelve modest miles that separated Woosung from Shanghai proved a difficult and, eventually, unhappy experience for the firm: it showed how deeply suspicious China was then of anything – no matter how obviously beneficial – that was fashioned by barbarian hands.

Since the 1850s Jardines and other foreign firms doing business in China had suggested building railways. It was part of the mood of the moment: Britain had started its own first commercial train service back in 1825, and railways now crisscrossed the island from Cornwall to Cromarty. In America, too, tracks were being laid as fast as the Pennsylvania steel mills could forge them. And yet by 1869, the year when thousands of labourers – Chinese labourers, no less – brought the Central Pacific metals to Utah and spiked them together with the rails from the Union Pacific in Omaha, and so knitted the country into one – by that same year not one single mile of railway had been laid in China. India was at the same time tottering under the weight of iron and brass; but China was still a nation of post roads and canals and bucolic inefficiency.

Jardines, in a hurry to make money, thought all of this a nonsense. China was, in their view, woefully out of step with the rest of the world. In letter after letter the firm kept beseeching the Manchus to make way for the modern. But the Court maintained an unyielding hauteur, turning down request after request, just as they had done to the merchants who wanted progress made on the Woosung Bar. Besides, the Chinese said in one letter, which I once saw in the Jardines archive, ‘railways would only be beneficial to China if undertaken by the Chinese themselves, and constructed under their own management.’

There was only one thing for it, so the westerners thought. Displaying the combination of mercantile acumen and barefaced cheek that (perhaps in part because it is so

Chinese

) continues to infuriate Beijing today, the firm decided to go ahead anyway, and in secret.

*

There was some hesitation – the first steps were taken in 1865, abandoned two years later and then revived in 1872. But finally the company had taken into their confidence the Shanghai city taotai – the official, appointed by the mandarinate, who was essentially the local mayor. The scheme, the foreigners thought, was bound to succeed.

The subterfuge had many elements and strategies. The company first had its Shanghai land agent buy up sections of real estate north of Shanghai, saying they were planning to build nothing more threatening than a horse road. At the same time they set up a London-based company, the Woosung Road Co. Ltd, and purchased a number of tiny steam railway engines made by a British firm called Ransomes and Rapier. The firm then quietly and surreptitiously laid a few miles of track, trusting that the taotai – who by now had been so taken into confidence that he had been persuaded to buy some WR Co. shares – would not step in to prevent it.

The rails, once unveiled, were just thirty inches apart – a little more than half the width of the railways that were then being built all across Britain and America. The trains made by Ransomes were small as well – they looked like models, the kind of engines that were found in amusement parks. The carriages, too, were child-sized, and open to the elements. The whole idea was to construct a railway that was on the one hand relatively inexpensive and on the other, and rather more important, would not terrify the Chinese public – to whom the idea of a foreign-made fire-breathing iron monster rushing about on iron tracks would be unsettling, to say the least. Nor could Jardines be accused of ostentation: nothing the company was doing on the Woosung road would or could be allowed in any way to challenge the supremacy of grandeur that was embodied in the Emperor or his appointed representatives.

The railway service duly opened with only reserved fanfare on 30 June 1876. The trains – pulled by a Ransomes engine appropriately called the Pioneer – were known locally as ‘devil's carriages’, and for many weeks no one would ride in them. Slowly, though, their convenience and economy caught on 187,000 people were counted as having ridden during the first year of operation.

The business would have continued to flourish, no doubt, had not disaster struck: in October 1877 a Chinese man was hit by a train and killed – whether it was suicide, murder, contrived misfortune or just a simple accident was never made clear. Jardines promptly compensated the family; but the Qing court in faraway Beijing then heard about the line (their taotai having carelessly omitted to inform them), complained that it had been built without permission and demanded that it be taken over by the government. Besides, the officials said, the railway was clearly a dangerous invention: the public, now back to being frightened by this evil monster, was in mortal fear.

And so a few months later, with a silk merchant acting as intermediary between the court and the barbarian merchants, the line was sold for a quarter of a million Shanghai taels. A court-appointed company took over the running of the little line for a day or so, and then, presumably as planned, the Qing officials shut the operation down, ordered the lines torn up within a few days and then shipped everything – rails, carriages, signals and the little toy trains – across the sea to Formosa.

Their people, they said, felt that fiery iron dragons – no matter how modestly sized – disturbed the essential harmony of the Empire. A temple to the Queen of Heaven was to be built on the site of the terminus – a proper propitiation, it was felt, to a deity whose tranquillity had been insulted by the foreigners. It was to be twenty more years before Woosung and Shanghai were connected by rail again – by which time China was on the verge of building (and not by its own devices, but with the help of the British, Americans, Russians, Germans and French) one of the biggest railway systems in the world. The mood by then had changed, profoundly. Fiery iron monsters now rumble across every province of the People's Republic – except for Tibet – and, far from disturbing celestial harmony, they are as essential to the well-being of the nation as rice and air. But that was not how matters were viewed in the China of the 1870s: back then in Woosung railways were foreign, they were unsettling and for the while at least they were not to be.

Nor, as it happened, was a railway for me in Woosung a century and a quarter later. Try as I might to find my way through the back streets by the docks, and try as I might to get to the station where it had all begun, I managed to get myself utterly and hopelessly lost. It had been a long day – up before dawn, transferring from ship to ship, rocking and lumbering up the estuary – and so when a red Toyota taxi stopped and the driver asked if I wanted a ride, and when I considered the trials of finding the station and then dealing with the complexities of buying a ticket, I uttered my cowardly agreement.

I loaded my rucksack into the back of the car, Lily and I wedged ourselves behind a formidable wall of Perspex security shield, which even Shanghainese taxis claim they need these days, and, with the radio blaring a noisy Foochow pop song, we headed past the Baoshan steel mills – and into the city. I told the driver to take us to a gateway beside the old Russian Consulate on Whangpoo Road. There was a ship docked behind it, I knew, in a cabin aboard which I had an invitation to sleep.

3

The City Without a Past

The tiny patch of brilliant green – it looked tinier, somewhat shrunken from when I had seen it last, five years before – lay half hidden behind a grove of London plane trees. There were shrubberies, a croquet lawn, the tattered leavings of a tennis net, a rusty roller with a dried-out wooden handle. The sharp scent of boxwood, of damp moss, of old pinecones. At the centre of the gardens a squat country house with a copper roof, dormer windows and ten Doric columns on the second floor. In places – the shadow of an old brass plate, the outline of iron letters on a garden gate – relics of what they called the place half a century ago: Hazelwood.

I had always liked the house. As a creation of the mid-thirties, it reeked of solid Home Counties suburbia, Betjeman country, although its creator insisted it was art deco and had it done up in canary yellow. It had been built as the residence of the

taipan

of Swires – or Butterfield & Swire, as it was known more precisely – the great British business house that along with its rival Jardine, Matheson & Co. once dominated trading in and around China. Swires ran China Navigation (CN Co.), one of the greatest shipping lines that worked the Yangtze. The grand men who were chosen to manage the firm for four- or five-year stints in Shanghai were immensely well looked after, treated like diplomats, or like the suzerains that in this peculiar hothouse of a city they invariably turned out to be. This house was part of the package.

I liked the house in part because of what it represented – mercantile confidence, colonial swagger, a certain rigorous high-mindedness – and in part because of who designed the building: Clough Williams-Ellis, one of Britain's more eccentric architects, and a man I had known a little. In the remote corner of north Wales where he lived, he cut a striking figure, not least by wearing plus-fours with canary-yellow socks and a cravat. His wife was a Strachey – his own bohemian air may have been half derived from his association with Bloomsbury – and he helped edit her anthologies of science fiction.

Architecture was his love, and eternal warfare against those he called ‘the Philistines' his self-appointed mission. With a view to creating beauty wherever he might, he designed buildings in almost every corner of the world. The quarry workers' tenement he inherited was turned into a house of fantasy and delight. He created an entire village near his home – and so fantastic did it turn out that it was later to become world-famous as the set for a cult television show.

*

He designed a baroque chapel in Hertfordshire and a Tudor castle on the Wye. He rebuilt the centre of one of Ireland's prettiest towns. He designed Lloyd George's tomb. And he designed – though he never visited – two properties for Swires in China: the taipan's house in the port city of Tientsin and this house in Shanghai, Hazelwood. What he would have thought of the old place now, sitting in the midst of so much modern philistinism – for modern Shanghai is nothing if not a philistine metropolis – is not hard to imagine.

Whenever I found myself in these parts I would always come and pay homage to the house and through it, to old Clough: I thought of the place rather as a friend, a place I could hold on to, or as somewhere that, in this most crowded and jostling of cities, I could get my bearings.

Once it was a home, comfortable, well set, with four tennis courts and a raked gravel drive. It was much the same kind of house as you might have visited for a Saturday lunchtime gin in genteel suburbs like Camberley or Virginia Water, or perhaps White Plains or Grosse Point – except that this was Shanghai, the most iniquitous town in the world, a cruel, mercenary city of white-hot passions and ice-cold hearts.

Not that those who lived at Hazelwood seemed party to any obvious iniquity, nor any cruelty or passion. You could remember what they looked like: the Swires men invariably tall, with square jaws, neat moustaches, kitted out in yellow cardigans and cavalry twill; the women matronly, competent, handsome, with the deep voices of the hockey field. (The first resident was the redoubtably square-jawed N. S. Brown, known to his staff, less than kindly, as Night Soil Brown.)

You could remember the innocent sounds, as well: the crunch of gravel as tyres pulled in under the porte-cochere, a sudden burst of laughter from the grass court, the patient clicking of the pruning shears by the matron with the trug of roses, the music drifting lazily from a wireless in the drawing room. The Chinese amah calling to the children to come inside for tea.

But these days what once was Hazelwood is just a small hotel, the Xinguo Bingguan, the Prosperous Kingdom Guest House. It was confiscated from Swires in the 1950s, like almost all the assets and property of the city's foreigners. Nowadays there is a glossy brochure: ‘Inside the Xing Guo Hotel the scenery is beautiful and peaceful. Big trees with exuberant foliage are alive with melodious birds. Fragrant wafts of flowers in full blossom breeze about. Several villas in European style are enwrapped by the greenery…’

What was once the main bedroom of the house, the one where the taipan slept and which had the french windows leading onto the terrace, and a view over the south lawn, has now been made into what they call a suite. The proprietors – the local government, a city ward in fact – will take sixty-five American dollars for each night you stay there, and they will charge it to your credit card. You are assured of privacy, just as the lairds of Hazelwood once were: the house is quite invisible behind the high brick walls that insulate it from the people and the traffic on Avenue Haig and Avenue Joffre and Rue Cardinal Mercier, and Bubbling Well Road, as the streets around were then known.

It was indeed made to be quite hidden from all of the city, amid which it nestled, secretly. It had been designed as a private house for one of Shanghai's most powerful foreign figures, a man who wanted a place tucked away from the bustle and the sin, a place where you could forget the existence of the city's 668 brothels and the calls for drinks at the longest bar in the world and the assorted terrors of Blood Alley – and for all the time he lived there, and for decades afterward, Hazelwood was private indeed.

But things have lately changed in Shanghai, and Hazelwood's splendid seclusion has gone. The privet hedges and the plane trees may still be there. But now, from another angle, an entirely new one, the house has recently become eminently and rather dramatically visible. A great new building has just gone up, one that dominates the city skyline and provides a place from which to gaze down on this and on all the old jumble of structures from Shanghai's extraordinary past.

It is impossible to miss: I saw it the very instant that I drew back the curtains of my cabin, and I almost jumped with surprise. The boat on which I was staying was moored at the northern end of the city reach, just downstream of the old Russian Consulate, at the place where the Whangpoo makes the final turn of the S-bend that once dictated where Shanghai was first built. My cabin faced south, and so the view was impeccable – directly down the river. The huge walls of old Imperial Shanghai ran down the Bund to the right. The suspension wires of the new Yangpu bridge – the second of two – glinted ahead in the distance. But on the left, bathed in white searchlight glare and winking with dozens of anti-collision lights, rose the extraordinary, unexpected, bright-red-tinted and breathtakingly ugly Oriental Pearl Television Tower, the tallest and, for the time being, unarguably the most vulgar structure in the East.

The Oriental Pearl Tower is a mongrel of a thing, a high-technology fantasy by an architect who was commissioned merely to build something that was defiantly and symbolically Twenty-first Century. It stands, perhaps with deliberately revisionist cheek, on top of the very spot where Jardines once had their main Pudong wharves and warehouses. It is 1535 feet high, all legs and bulbs and pods and needles; it looks like an insect. It is not unimpressive: those who see it for the first time gasp, for it quite dwarfs every other building in Shanghai by both its scale and its bellowing chutzpah.

At night it looks as though it is about to take off. (‘I wish it would,’ muttered Lily, who at first thought it a very disagreeable addition to the city's skyline.) By day it stands suspended above the hurrying crowds, looking dark and vaguely menacing, half lighthouse, half gibbet. It is of course suggestive of tomorrow, but at the same time it somehow seems to be a warning of tomorrow. Some people who see it shudder: it is so huge, it went up so quickly

*

and on close inspection it is so badly made. And indeed, by being so gigantic, so hurriedly done and so shoddily put together it does manage to symbolize – in more ways than its makers know – the realities of the fast-growing new city that sprawls around and beneath it. But that is not why I found it so menacing a structure: I think it was the fact that it combined its sheer ugliness with its utter domination of the view. How, I kept wondering to myself, could city fathers with any sense of civic pride have permitted such a thing?

A deliriously proud citizen named Mr Su took me to the top of the monster. According to his thickly laminated business card, he was its Vice General Manager, and I gathered from his ceaseless chatter that his task was for him a labour of love – he adored both his building and all of new Shanghai. As we stepped from the lift, he spread wide his arms and began to point out grand and new and ever more glittering structures that were rising around the city on every side, down amid a forest of construction cranes. For a while I happily ignored him: I was content to peer down through the grey-blue haze of factory smoke and car exhausts until I found the tiny landmark patch of green that was Hazelwood, far away to the west. I spent some while gazing fondly down and across at it, getting my bearings in a way I had never imagined possible. It was infinitely more pleasurable to do this, to shut out Mr Su's unending drumbeat of statistics and notable achievements and, in a poignant sort of way, to savour the connection and reflect on the dissonance between Clough's old house down there and this new colossus on top of which we were standing.

But eventually Mr Su became less easy to ignore. He moved away from the windows, invited me into another lift, took us up a few floors, then down a few more, along a corridor and onto an escalator until I was quite comprehensively disorientated. He had by now stopped talking of the changes that were being wrought down in the city, bubbling away instead with explanations of the specific architectural details of his own building. He did so at a great clip, shouting all the while, like a circus barker.

‘The symbol of this city is – what? The pearl. Pearl of the Orient, yes? Well, look at this: how many pearls you see?’

We seemed to be standing now near one of the tower's three elephantine legs, and I saw he was waving pictures before me, jabbing at each of them with his finger.

‘Look at Seattle. Only one pearl at the top. Look at Moscow. Look at Toronto – bigger than us, yes – but how many pearls? One, just one.

‘Now look up, look at ours.’

And I looked, and halfway up the closest leg was a thirty-foot sphere of red glass, like a thrombosis.

‘Er – a pearl?’ I ventured, hesitantly.

‘Yes – exactly.’ He looked amazed at my insight. ‘And look – there's another, and another.’

One pearl, so-called, on each of the three legs. One immense sphere – another pearl, I should say – where the three legs joined. Then five more smaller globule-pearls, each sixty feet in diameter, up along the main shaft. Another truly massive one at the top of this shaft, then a smaller one farther up on a subsidiary and narrower shaft, after which was the spire and on top of this the television antennae.

‘Eleven pearls. Eleven! How's that for a symbol? We wanted to be different, and we wanted to make a statement about who we are. So we truly are the Pearl of the Orient now, don't you think?’

Lily was stifling her laughter at all of this – though I rather sensed she was changing her mind about the tower now that we had taken this tour; she had nudged me at one point and said that the building was making her feel ‘quite proud’ – but there was no stopping Mr Su. ‘Come into the elevator. We go to the topmost pearl. The most private room in Shanghai. Here you will get away from everything. You want to hold a secret meeting, you hold it here, in full view of everyone – but no one can get here. You understand?’

Men in red uniforms stood as lift doors opened and shut, girls in red uniforms took their positions on red carpets inside the lifts, red light filtered in through the red glass. (‘Canadian, imported specially. Far too expensive. The old buildings here only ever had blue glass, or clear glass, so we are much better, yes?’) There was a fiery anger to the inside of the tower, a furnace feeling that was not much relieved when finally we arrived inside the sphere – the pearl – at the top of Shanghai. The place was still plastery with makings, workers scurrying around hammering and drilling and tightening things, and there was sawdust on the red carpet. The light that filtered in was tinted rose.