The Road Narrows As You Go (52 page)

Read The Road Narrows As You Go Online

Authors: Lee Henderson

34

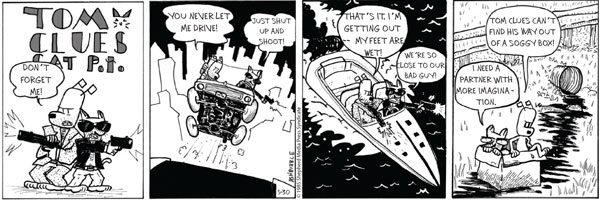

STRAYS

⦠go at throttle up â¦

⦠go at throttle up â¦

No, not these words. Not yet.

Anyway we were done. The Christmas cartoon was complete. And it was Christmas of eighty-five. After a five-year struggle up all the hills, psychological, technical, creative, to say nothing of the hill under our shoes that led to No Manorsâwe climbed Stoneman Street enough times to put on muscleâit looked as though the bulk of the twenty-two minutes

had been animated. Add it all up, there might be ninety seconds missing. Rachael phoned Wendyâwho was travellingâto let her know all that remained for us to do was improve the pace in a few transitions, redraft the muzziest movements, and edit in establishing shots between a couple of the sequences in the

mise en scène

. Once that was done, we'd be ready to make a final cut with the soundtrack.

Wendy yelled into the phone: Rachael, I can hardly hear you. I'm on my stupid Motorola. I'm literally standing on a Christmas parade float covered in fake snow and there's life-sized mascot versions of my characters next to me waving to the families of Bethesda lined up on the street. It's cute. You should see me. I'm throwing candy canes at toddlers while Frank meets with senators and lobbyists. I gotta go. Just tell me this means I can pitch the cartoon to the networks to air next summer.

Yes! Rachael shouted.

Our thousands upon thousands of prelim drawings, cell paintings, and the rest of the prep work of the early eighties finally paid off. Now we had all these pieces of finished animation to pull from. If we needed Buck's head to do an owlspin in minute nineteen we could pull from the same action drawn for minute two. Rachael filed all the animation pieces, from paper sketch to trace paper to cells, in an enormous steel cabinet, in carefully labelled folders (

Murphyâleft arm waving

;

Francisâears twitching

). We had all sixteen phases in the standardized walking postures for each character, and perspective variations (running away from or towards the camera). Notes in each folder described the exact time signatures when these pieces had been used. Rachael's system let us make swift progress on the story after three years of work to get to minute twelve, and we completed the last ten minutes in a year.

Meanwhile, various pavilion sketches kept coming back rejected by one Olympics committee after another. The Americans didn't approve of watercolour (sloppy, too French) and vetoed so much detail (too expensive). The internationals found the composition uneven and ditto the

proportions. The pavilion committee nixed Wendy's colour schemes, and the Canadian hosts thought the subject matterâanimals doing Olympic eventsâmight offend some audiences.

A curse on the Olympics and all their insane committees! Wendy shouted one night, and threw a balled-up poster-sized sheet of paper in the air, out an open window, and wanting to toss her editor and defenestrate the whole Shepherd Media Syndicate, too, while she was at it. She got desperate and began to throw all her pavilion sketches our way to see what would happen if we inked them. This was eighty-six now, and our teeth were fairly sharpened by the hours and hours we had sunk into drawing reams of storyboards, breakdowns, character shots, notan treatments, and finals for the Christmas specialâand now she wanted us to put time into helping her with the Olympic pavilion.

Challenger, go at throttle up.

Roger, go at throttle up.

â¦

Challenger, go at throttle up.

Roger, go at throttle up.

â¦

Challenger, go at throttle up.

Roger, go at throttle up.

Those words. Those words hang in our minds like wind chimes, they jingle at the slightest motion of our memories. That Tuesday in January tore the decade in half. We remember the year began with a choir of hope exploding and disintegrating over the Atlantic Ocean. America watched as the space shuttle

Challenger

left for outer space and all of a sudden burst into flames and became two then three trails of smoke falling slowly and inexorably back to Earth. It happened so fast the eye didn't have time to accept the horror. There was a schoolteacher on board and classrooms all across North America were watching live broadcasts on projection screens

in gymnasiums. An astronaut to identify with was up there. We tuned in, too. Who didn't?

Challenger

vanished in the sky with its seven-member crew. You wanted to avert the eyes of the entire world from this sorrow plummeting out of thin blue air.

News of the disaster consumed our lives. We stopped doing anything else and read about the

Challenger

in all the papers and magazines and watched television coverage devoted to the disaster, and to the history of space travel, and saddening portraits of the astronauts on board who perished.

Nancy and I are pained to the core ⦠We've never lost an astronaut in flight. We've never had a tragedy like this, President Reagan said in his address to the nation.

One underlying purpose of every mission to space is to prepare for the safety of the next mission, said a former NASA aerospace engineer who had worked closely with Major Aloysius Murphy in Panama on safety systems and the first iterations of the shuttle cockpit. Talking in a panel about the history of disasters, the engineer said, Every astronaut knows you might not come home.

We wondered what an astronaut thinks of as the shuttle's cabin engulfs with flames. Strapped to your seat, you think, This is what I dreamed of doing all my life and I knew it was dangerous when I signed up and my mission will never be forgotten.

This

was my mission. Disaster was my mission.

At the time of the

Challenger

disaster, Frank was in D.C. wooing senators and congressmen over shrimp cocktails, martinis, etcetera in an attempt to shore up support for the financial quango, and Wendy was in Los Angeles for meetings with network execs to pitch her

Strays

summer Christmas special. She went as writer-producer and took Rachael as ipso facto director of the cartoon for silent support. The potential for failure seemed very much at handâthere it was, the VHS tape we made of the cartoon.

The first meet was with Brian Lynch, Head of Children's Programming at ABC.

If ABC buys now, the network could air it this coming July, Wendy said.

Brian Lynch took the cassette. He was honoured to be the first outsider to view the cartoon so many industry insiders were affectionately calling

Apocalypse, Strays

. Did the cartoon even exist or was it something Wendy said to sound mysterious? He kept looking back and forth between Wendy and Rachael waiting for us to confess there was no cartoon. Now Lynch knew for sure. A few minutes into the story, he was laughing. It's not what I expected at all but that's the point, right? I like the approach, or the lack of. It's fresh. Funny.

Then a secretary burst through the door in tears and switched off the VCR to turn on the live news. They never watched the rest of the Christmas special.

Let me think on it and get back to you, a teary-eyed Brian Lynch said as he led Wendy out of his office. Then he burst into a donkeysob, and covering his eyes with his arm, slammed the door of his office shut.

The noise outside Lynch's office reminded her of the time she had visited the Hexen Diamond Mistral offices in Manhattan. To get to the elevators we faced an entire floor of paroxysmsâracing to react to the disaster, employees dug in like soldiers, telephones blasting at every desk. It was like the opening volley of a military action. Cries for help. Running from desk to desk delivering shorthand transcriptions of urgent phone interviews. No one on the floor noticed us walk by, least of all us.

Strays

was totally insignificant right now. The sky over America was still filled with rocket debris on its long arc to the ground. There were journalists in the room who had interviewed the astronauts.

35

STRAYS

She had booked three appointments over two sere days in Los Angeles, with Lynch at ABC the first day, and with CBS's president, Norman Zederbaum, and Peter Patterson at NBC on the second afternoon. The network offices were in entirely different suburbs, hours apart from each other, like feuding children with lines drawn between them. President Zederbaum was a hale old gentleman, broad shouldered, a veteran of two wars, the kind of man Wendy saluted on the street out of plain courtesy, a hello to age's inevitable provisions of wisdom, of which Zederbaum

seemed to have accumulated more than his fair share. Once energetically handsome, if not tall, as a producer akin to Wendy's mother but on a grander scale, Zederbaum had been a relentless cowboy on the sound stage, rounding up the contract actors for cattlecalls and barking orders at unionized technicians. Much too old to do anything so physical for the network now, what luck he was president. Meetings were his milieu in advanced yearsâhe took a few a week and golfed the rest. That wisdom from experience, mostly made up of backlot gossip good enough for blackmail, so long as his memory held out, that's what gave him influence. After that self-portrait, he asked Wendy to show him the cartoon.

When the Christmas special was over, Zederbaum turned to her and said, Dear, are you on drugs?

Zederbaum's underling was a man named Tom

TK

Watson. TK was another example of this same sort of unstoppable gentleman who had cut his teeth in the Golden Era of Television and could have retired when Ed Sullivan introduced the Beatles. But he kept on going out of a love of money. His eyes were black balls sunken in shadow. His deep, sombre voice came with its own echo, rattling around in the cave of his throat. The thin hair on top of TK Watson's head was the grey of lint. This was the Head of Children's Programming.

TK Watson spoke as if delivering a sermon over the grave of a child. You might not know it but I'm the biggest fan of

Strays

, have been since day one. Own all the treasuries. I do. More than you'll ever know ⦠More than you'll ever know

I

wanted to be the one to bring

Strays

to TV. A summer Christmas specialâthis rumour made me laugh the first time I heard it, and I still laugh at it even after I've seen theâ. The pitch is still funny.

TK Watson heaved himself forward in his chair, leaned his elbows on the table, and tapped his fingertips together in the air in front of him as he continued to speak. So, gee, what else to call it but a

masterpiece

. Deserves to be in a modern art museum, doesn't it? The masterpiece has arrived and

we've

all

had a chance to take a look, and we are unfortunately going to have to pass. Yes.

To

pass

, she said. That's not your

final

decision? You want a few changes.

No, this is just too far out, Wendy. You made a cartoon for MTV, not CBS ⦠We could air this at midnight, I guess.

This is not

art

, this is ⦠nihilism, said the president of CBS. He spoke to her as if to scold an underling. He stomped around the office. Zederbaum could not sit down because this was not his office, not even his floor of the building, and so the president paced TK Watson's office like the ghost in

Hamlet

, speaking in a wet rasp made worse by his high collar and necktie pressing against his ancient Adam's apple. I'm not impressed, Wendy, I am not. This cartoon was not what I hoped for. You've compromised your good taste to please a failed generation. In an era of profound anxiety, children need cartoons with a calm, even tempo. Not this rampa-bam-bam, machine gun rock video editing you do here.

TK Watson took over from his apoplectic boss. You borrow from the history of animation in a willynilly spectacle that is more disorienting than our network is prepared for. Because I hope I

never

gave you the impression we wanted something like

Pee-wee Herman

or the old

Batman

show with Adam West, no, no, we always hoped this was a straightforward adaptation of your strip. This experiment is courageous, unforgettable.