The Road to Little Dribbling (29 page)

Read The Road to Little Dribbling Online

Authors: Bill Bryson

“Happens all the time,” Fran said. She once came upon a beach containing hundreds and hundreds of bicycle seats. She has also found computers, refrigerators, and vacuum cleaners. Lots more floats than you would ever expect, it seems.

—

I spent the night in Dunwich at a jolly nice pub called the Ship. Dunwich is an odd place in that it mostly isn’t there anymore. In the twelfth century, it was one of the most important ports in England, nearly three times the size of Bristol and not that much smaller than London. It was home to four thousand people and boasted eighteen churches and monasteries. But in 1286 a mighty storm swept away four hundred houses, and further storms in 1347 and 1560 took away much of the rest. Today most of the original Dunwich is underwater. St. Peter’s Church is nearly a quarter of a mile offshore, and some people with no attachment to acoustic reality claim that you can still hear its bell ringing late at night if you listen carefully. All that is left of Dunwich these days is a beach café, a few houses, a ruined priory, and its chirpy pub.

In the evening, in a desperate effort to keep from starting to drink too early, I went for a longish walk and ended up at the seafront. Ships, prettily lit, slid across the horizon, presumably headed for or coming from Felixstowe, just around the corner to the south.

I had just read in

The Economist

that Felixstowe is now the world’s leading exporter of empty cardboard boxes. The world sends Britain its products and Britain sends back the boxes. It isn’t that Britain is more vigilant than other nations about gathering up old cardboard, but more that other nations don’t export it. They recycle it. Britain prefers to send its discarded packaging abroad for expert handling by poorly paid people in distant places. In 2013, the United Kingdom exported more than one million metric tons of cardboard, considerably more than any other nation proportionate to its population.

And with that proud thought to sustain me, I walked back up to the Ship to toast, in my own private way, my adopted nation.

Chapter 15

Cambridge

O

N THE PLATFORM AT

Cambridge station was a poster for a book by Jeremy Clarkson, a popular television presenter and columnist who has fashioned a very lucrative career out of being cheerfully boorish. The poster had a photo of Clarkson looking adorably doleful and a caption that read: “Dads. Everything they say. Everything they do. Everything they wear. Its all completely wrong.” Oh, the wit. But note the absence of the apostrophe in “its.” I know it is way too much to ask that a television presenter should take an interest in the literacy of his posters, but surely someone at Penguin ought to care.

We have now reached a level in which many people are not merely unacquainted with the fundamentals of punctuation, but don’t evidently realize that there are fundamentals. Many people—people who make posters for leading publishers, write captions for the BBC, compose letters and advertisements for important institutions—seem to think that capitalization and marks of punctuation are condiments that you sprinkle through any collection of words as if from a salt shaker. Here is a headline, exactly as presented, from a magazine ad for a private school in York: “Ranked by the daily Telegraph the top Northern Co-Educational day and Boarding School for Academic results.” All those capital letters are just random. Does anyone really think that the correct rendering of the newspaper is “the daily Telegraph”? Is it really possible to be that unobservant?

Well, yes, as a matter of fact. Not long ago, I received an e-mail from someone at the Department for Children, Schools and Families asking me to take part in a campaign to help raise appreciation for the quality of teaching in Great Britain. Here is the opening line of the message exactly as it was sent to me: “Hi Bill. Hope alls well. Here at the Department of Children Schools and Families…”

In the space of one line, fourteen words, the author has made three elemental punctuation errors (two missing commas, one missing apostrophe; I am not telling you more than that) and gotten the name of her own department wrong—this from a person whose job is to promote education. In a similar spirit, I received a letter not long ago from a pediatric surgeon inviting me to speak at a conference. The writer used the word “children’s” twice in her invitation, spelling it two different ways and getting it wrong both times. This was a children’s specialist working in a children’s hospital. How long do you have to be exposed to a word, how central must it be to your working life, to notice how it is spelled?

People everywhere have abandoned whole elements of grammatical English, and I don’t understand it. I was watching a Brian Cox television documentary in which he was standing in a field in Mexico talking about bombardier beetles when he said: “The bombardier beetle and me, and in fact every living thing you can see, are exposed to the same threat…Me and my friend the beetle have both reached the same solution.” Now don’t get me wrong. I have great respect for Brian Cox. He has a brain so big that it crosses whole time zones, and he is normally impeccable with the language, so why on earth would he say “the bombardier beetle and me” when it is surely more natural, and clearly more respectable, to say “the bombardier beetle and I”? Soon after this, I watched a documentary by another eminent young scientist, Adam Rutherford, and he said: “Now I’ve got just 33 vertebrae in my spinal column, but Belle here [a boa constrictor] has got 304, and the amazing thing is it’s the same handful of genes that determine how many vertebrae both me and her have.”

Then I heard Samantha Cameron, wife of the prime minister, say to a television interviewer, “Me and the kids help to keep him grounded.”

So here is all I am saying about this. Stop it.

—

I thought it would be quiet in Cambridge on a Sunday, but it was the very opposite. The streets were teeming with tourists and shoppers, as if there were a festival on, but it was just the usual Sunday shuffle, people passing their day of rest by aimlessly wandering between shops, with lunch and an occasional hot beverage and day-old pastry thrown in. It used to be that on Sunday mornings the only people you would see in a commercial district were vagrants searching through litter bins. In those days the only shops open on Sundays were gas stations and newsagents, so all you could buy were cigarettes, sweets, and newspapers. If you had forgotten to shop for food on Saturday, you had a candy bar and a glass of water for dinner.

How the world has changed. Now there were more people on the streets of Cambridge than lived in Cambridge. Some streets were packed primarily with locals, some primarily with tourists. Every few steps some cheerful young person would thrust a leaflet at me for some kind of a tour—walking tour, ghost tour, hop on / hop off bus tour. Every shop doorway and postcard rack, indeed every available space within sight of a historic building, was crowded with gaggles of foreign youngsters, usually with matching backpacks. I wanted a coffee, but the cafés were filled to overflowing, so I went to a John Lewis department store on the presumption that I would find a quiet café there, up on the top floor, with views over rooftops. John Lewis stores always have a café with a view over rooftops, and it did here, too, but it was packed, with a queue stretching back to the Keep Calm and Carry On giftware section. At least two dozen people hadn’t even reached the plastic trays yet. The idea of creeping along behind people who couldn’t decide between a pain aux raisins and a fruit cup, or who wondered if they could just have a daub of Dijon on the side and were happy to stop the line while some hapless skivvy went down to the cellars to fetch a new jar, or who got to the cash register and didn’t have the right money and had to send a search party to fetch Clive—well, I couldn’t face that. So I gave up on coffee and went and looked at televisions because that’s what men do in John Lewis stores. There were over three hundred of us, moving solemnly up and down the rows of televisions, considering each in turn, even though the televisions were all essentially identical and none of us needed a television anyway. Then I examined laptops—tapped the keys, opened and closed the lids, nodding ruminatively, like a judge at a vegetable-growing competition—and finally waited my turn to listen to the demonstrator Bose headphones. I dropped the headphones onto my ears and immediately I was in a tropical jungle—and I mean right in it, aurally immersed—listening to cawing birds and skitterings in the undergrowth. Then I was in Manhattan at rush hour with murmured voices and honking horns. Then in a cleansing spring shower with just an occasional crack of thunder. The fidelity was uncanny. Then I opened my eyes and I was back in John Lewis in Cambridge on a Sunday. It was perhaps little wonder that six men were waiting behind me for a turn on the headphones.

I strolled over to Trumpington Street and to the Fitzwilliam Museum, which to my mind is Cambridge’s most luscious treasure. I only recently discovered the Fitzwilliam. I had always supposed it to be small and charmingly overstuffed with treasures, like Sir John Soane’s Museum in London, but in fact it is vast and grand and airy, like the British Museum transported to a secondary street in Cambridge. Uniquely among Cambridge institutions, it was only moderately busy. Better still, the café had empty tables. Suppressing a whoop of joy, I ordered an Americano coffee and a piece of walnut cake, which was small, dry, and expensive, just the way the English seem to like it, and thus was able, twenty minutes later, to embark on an exploration of the Fitzwilliam’s echoing galleries in a refreshed state.

It occurred to me that I had no idea who the Fitzwilliam behind the museum was, so afterward I looked it up. It was Richard Fitzwilliam, seventh Viscount Fitzwilliam, who in life never did much of anything other than spend a good deal of it in France, where he sired three children illegitimately by a ballet dancer. Beyond that his private life is “deeply obscure,” according to the

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography,

which knows a thing or two about being deeply obscure. Fitzwilliam died in 1816, never having married, and left his art and a large sum of money to Cambridge University to build a museum in his name, which it faithfully did.

The Fitzwilliam Museum doesn’t normally attract a great deal of attention, but in 2006 it leapt into the news when a visitor named Nick Flynn tripped on a loose shoelace and swept three precious Qing vases off a windowsill, smashing them to bits and causing damage of between £100,000 and £500,000, depending on which part of the Google universe you consult. Photographs of the aftermath of the occasion, available on the Internet, show that Flynn’s trip was possibly the greatest shoelace fall in history, for he managed to sweep clear a windowsill that was perhaps fifteen feet long and leave the vases in thousands of small pieces on the floor. Police arrested Flynn on the suspicion that the damage was intentional, but the charges were subsequently dropped. “I actually think I did the museum a favor,” Flynn told the

Guardian

sometime afterward. “So many people have gone there to see the windowsill where it all happened that I must have increased the visitor numbers. They should make me a trustee.” Not surprisingly, the museum did not do that. Instead, it wrote to Flynn and politely asked him not to come back anytime soon. It was all it could do.

I had read that the vases had been repaired and were back on display, though now safely behind tempered glass. I asked an attendant where they were and she directed me to a glass case that I had in fact just been peering into. The repairs are so good as to be essentially invisible. I had to look hard a second time to see even the tiniest line of repair. Speaking as someone who has never glued anything without also at the same time unintentionally gluing at least three other things, I was impressed.

I spent an hour and a half in the Fitzwilliam, not counting snack time, and then strolled around the corner to the Scott Polar Research Institute Museum, which, let me say right now, is one of the best small museums in the country, but it was closed, alas. So I went to the Whipple Museum of the History of Science, but it was closed, and then to the Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences, and the Museum of Classical Archaeology, and they were closed, too. The Museum of Zoology was closed altogether for refurbishment. To my joy, I found that the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology was open on Sunday, but it was closing for the day just as I arrived.

“Perhaps I’ll come back tomorrow,” I said.

“We’re closed on Mondays,” said the man.

—

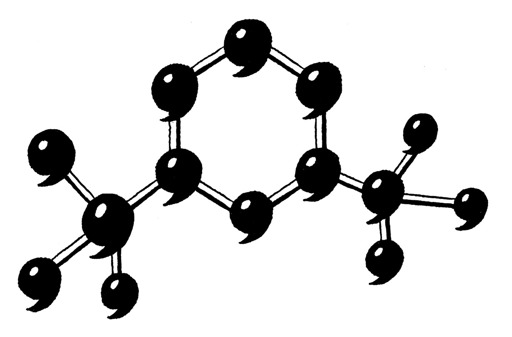

So I just wandered around. By happy accident, I cut down a back street called Free School Lane and chanced upon the building that was home of the famous Cavendish Laboratory from 1874 to 1974. Somebody once observed to me that probably no small patch of earth has produced more revolutionary, earth-changing thinking than an area a few hundred yards across in the center of Cambridge. Here at various times you have had Isaac Newton, Charles Darwin, William Harvey, Charles Babbage, Alan Turing, John Maynard Keynes, Louis Leakey, Bertrand Russell, and more other original thinkers than I could list here. Altogether, ninety people from Cambridge have won Nobel Prizes, more than any other institution in the world, and the greater portion of these—nearly a third—came out of this anonymous building on Free School Lane. A plaque on the wall noted that this was the building where J. J. Thomson discovered the electron in 1897, but there was nothing at all to indicate that this was also where the structure of DNA was revealed by Francis Crick and James Watson or where James Chadwick discovered the neutron or Max Perutz unraveled the mystery of proteins. Twenty-nine members of the Cavendish have won Nobel Prizes, which is more than most countries. Four members won in 1962 alone: James Watson and Francis Crick in Physiology or Medicine and Max Perutz and Sir John Kendrew in Chemistry.