The Rule of Four (21 page)

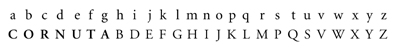

He showed me a sheet of paper he’d prepared, with two lines of letters running parallel to each other.

“Here’s a very basic cipher alphabet,” he said. “The top row is what you call the plaintext, the bottom row is the ciphertext. Notice how the ciphertext begins with our keyword,

cornuta

? After that, it’s just a regular alphabet, with the letters from

cornuta

removed so they don’t get duplicated.”

“How does it work?”

Paul picked up a pencil from his desk and began circling letters. “Say you wanted to write ‘hello’ using this

cornuta

cipher. You would start with the plaintext alphabet on top and find ‘H,’ then look at its equivalent in ciphertext below it. In this case, ‘H’ corresponds to ‘B.’ You do that with the rest of the letters, and ‘hello’ becomes ‘buggj.’ ”

“That’s how Colonna used

cornuta

?”

“No. By the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Italian courts had much more sophisticated systems. Alberti, who wrote the architecture treatise I showed you last week, also invented polyalphabetic cryptography. The cipher alphabet changes every few letters. It’s much harder.”

I point to his sheet of paper. “But Colonna couldn’t have used anything like that. It just makes gibberish. The whole book would be full of words like ‘buggj.’ ”

Paul’s eyes lit up. “Exactly. Complex encipherment methods don’t produce readable text. But the

Hypnerotomachia

is different. Its ciphertext still reads like a book.”

“So Colonna used the riddles instead of a cipher.”

He nodded. “It’s called steganography. Like writing a message in invisible ink: the idea is that nobody knows it’s there. Francesco combined cryptography and steganography. He hid riddles inside a normal-sounding story, where they wouldn’t stand out. Then he used the riddles to create deciphering techniques, to make it harder to understand his message. In this case, all you have to do is count the number of letters in

cornuta,

which is seven, then string together every seventh letter in the text. It’s not that different from using the first word of every chapter. Just a matter of knowing the right intervals.”

“That worked? Every seventh letter in the book?”

Paul shook his head. “Not the whole book. Just a part. And no, it didn’t work at first. I kept coming up with nonsense. The problem is figuring out where to start. If you choose every seventh letter beginning with the first one, you get a completely different result than if you choose every seventh letter beginning with the second one. That’s where the riddle’s answer plays a role again.”

He pulled another page from his pile, this one a photocopy of an original page from the

Hypnerotomachia.

“Right here, in the middle of this chapter, is the word

cornuta,

spelled out in the text of the book itself. If you begin with the ‘C’ in

cornuta,

and write down every seventh letter for the next three chapters,

that’s

how you find Francesco’s plaintext. The original was in Latin, but I translated it.” He handed me another sheet. “Look.”

Good reader, this past year has been the most trying I have endured. Separated from my family, I have had only the good of mankind to comfort me, and while traveling the waters I have seen how flawed that good can be. If it is true, what Pico said, that man is pregnant with all possibilities, that he is a great miracle, as Hermes Trismegistus claimed, then where is the proof? I am surrounded on one side by the greedy and the ignorant, who hope to profit by following me, and on the other side by the jealous and the falsely pious, who hope to profit by my destruction.

But you, reader, are faithful to what I believe, or you could not have found what I have hidden here. You are not among those who destroy in God’s name, for my text is their foe, and they are my enemy. I have traveled broadly in search of a vessel for my secret, a way to preserve it against time. A Roman by birth, I was raised in a city built for all ages. The walls and bridges of the emperors stand after a thousand years, and the words of my ancient countrymen have multiplied, reprinted today by Aldus and his colleagues at their presses. Inspired by these creators of the old world, I have chosen the same vessels: a book and a great work of stones. Together they house what I will give to you, reader, if you can understand my meaning.

To learn what I wish to tell, you must know the world as we have known it, who studied it most of any men in our time. You must prove yourself a lover of wisdom, and of man’s potential, so that I will know you are no enemy. For there is an evil abroad, and even we, the princes of our day, do fear it.

Carry on, then, reader. Strive wisely for my meaning. Poliphilo’s journey grows harder, as does mine, but I have much more to tell.

I turned the sheet over, looking for more. “Where’s the rest of it?”

“That’s it,” he said. “We have to solve more to get more.”

I looked at the page, then up at him in amazement. In the back of my mind, from a corner of unsettled thoughts, came a tapping noise, the sound my father always made when he was excited. His fingers would drum the rhythm of Corelli’s Christmas Concerto, twice as fast as any allegro movement, on whatever surface he could find.

“What are you going to do now?” I asked, trying to stay afloat in the present.

But the thought occurred to me anyway, putting the discovery in perspective: Arcangelo Corelli finished his concerto in the early days of classical music, more than one hundred years before Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Even in Corelli’s day, though, Colonna’s message had been awaiting its first reader for more than two centuries.

“The same thing you are,” Paul said. “We’re going to find Francesco’s next riddle.”

Chapter 13

Every hallway in Dod is empty as Gil and I return to the room, numbed by the long walk north from the parking lot. An airy silence prevails throughout the building. Between the Nude Olympics and the Easter festivities, every soul is accounted for.

I turn on the television for word of what’s happened. The local networks carry the Nude Olympics on the late news, after there’s been time to edit the footage, and the runners in Holder Courtyard float across the screen in a blur of whites, blinking under the glass like fireflies trapped in a jar.

At last the female news anchor returns to the screen.

“We have breaking news on our top story.”

Gil emerges from his bedroom to listen.

“Earlier tonight we reported to you about what may be a related incident at Princeton University. At this hour the accident at Dickinson Hall, which some witnesses describe as a fraternity stunt gone wrong, has taken a tragic turn. Officials at Princeton Medical Center confirm that the man, reportedly a university student, has died. In a prepared statement, Borough Police Chief Daniel Stout repeated that investigators would continue to examine the possibility that, quote, nonaccidental factors had played a role. In the meantime, university administrators are asking students to remain in their rooms, or to travel in groups if they need to be outside tonight.”

In the studio, the anchor turns to her cohost. “Clearly a difficult situation, given what we saw earlier at Holder Hall.” Returning to the camera, she adds, “We’ll be coming back to this story later in the hour.”

“He died?” Gil repeats, unable to believe it. “But I thought Charlie . . .” He lets the thought trail off.

“A university student,” I say.

Gil looks up at me after a long silence. “Don’t think like that, Tom. Charlie would’ve called.”

Against the far wall, the framed picture I bought for Katie sits at an uncomfortable cant. I dial Taft’s office, just as Gil returns from his bedroom and hands me a bottle of wine.

“What’s this?” I ask.

The phone at the Institute rings over and over. Nothing.

Gil steps toward the makeshift bar he keeps in the corner of the room, grabbing two wineglasses and a corkscrew. “I need to relax.”

There’s still no answer at Taft’s, so I reluctantly put down the receiver. I’m just about to tell Gil how sick I feel, when I glance over and realize that he looks even worse.

“What’s wrong?” I ask.

He tops the glasses off. Taking one in his hand, he raises it to me, then takes a sip.

“Have some,” he says. “It’s good.”

“Sure,” I say, wondering if he just wants someone to drink with. But the thought of wine is turning my stomach.

He waits, so I nip at my share. The burgundy stings going down, but it has the opposite effect on Gil. The more he’s got in him, the better he starts to look.

I tip my glass back. Snow rolls across the pools of light from the post lanterns in the distance. Gil drains his second glass.

“Take it easy, chief,” I say, trying to sound nice about it. “You don’t want to have a hangover at the ball.”

“Yeah, right,” he says. “I have to be at the caterer’s tomorrow by nine. I should’ve told them I don’t even go to class that early.”

It comes out sharp, and Gil seems to catch himself. Picking up the remote from the floor, he says, “Let’s see if there’s anything else on.”

Three different networks are broadcasting from somewhere on campus, but when there doesn’t seem to be any new information, Gil gets up and starts a movie.

“Roman Holiday,”

he says, sitting back down. A distant ease comes over his face. Audrey Hepburn again. He puts down the wine.

The longer the movie stays on, the more I find that Gil is right. No matter how heavy my thoughts are, sooner or later I keep coming back to Audrey. I can’t get my eyes off her.

After a while, Gil’s focus seems to cloud over a little. The wine, I guess. But when he rubs his forehead and focuses a second too long on his hands, I sense there’s more to it. Maybe he’s thinking of Anna, who broke up with him while I was at home. Thesis deadlines and planning the ball undid them, Charlie told me, but Gil never wanted to talk about it. Anna was a mystery to us from the beginning; he almost never brought her to the room, though at Ivy, I’d heard, they were never apart. She was the first of his girlfriends who couldn’t recognize which one of us was picking up the phone, the first who sometimes forgot Paul’s name, and she never stopped by the room if she knew Gil wasn’t there.

“You know who looks a little like Audrey Hepburn?” Gil asks suddenly, catching me off guard.

“Who?” I say, dialing Taft’s office again.

He surprises me. “Katie.”

“What made you think of that?”

“I don’t know. I was watching you two tonight. You’re great together.”

He says it as if he’s trying to remind himself of something dependable. I want to tell him that Katie and I have had our ups and downs too, that he’s not the only one who struggles in a relationship, but it would be the wrong thing to say.

“She’s your type, Tom,” he goes on. “She’s

smart.

I don’t even understand what she’s saying half the time.”

I hang up the phone when there’s still no answer. “Where is he?”

“He’ll call.” Gil takes a long breath, trying to ignore the possibilities. “How long’s it been with Katie?”

“Next Wednesday makes four months for us.”

Gil shakes his head. He’s broken up three times since Katie and I met.

“Do you ever wonder if she’s the one?”

It’s the first time anyone has asked that question.

“Sometimes. I wish we had more time. I worry about next year.”

“You should hear how she talks about you. It’s like you’ve known each other since you were kids.”

“What do you mean?”

“I found her at Ivy once, taping a basketball game for you on the TV upstairs. She said it was because you and your dad used to go to the Michigan–Ohio State game together.”

I hadn’t even asked her to do it. Until we met, she’d never followed basketball.

“You’re lucky,” he says.

I nod my agreement.

We talk a little more about Katie, then Gil slowly returns to Audrey. His expression lightens, but eventually I can see the old thoughts return. Paul. Anna. The ball. Before long he reaches for the bottle. I’m just about to suggest that he’s had enough to drink, when a dragging sound comes from the hallway. The outside door opens, and Charlie stands in the sallow light of the hall. He looks bad. There are blood-colored stains on the cuffs of his clothes.

“You okay?” Gil asks, standing up.

“We’ve got to talk,” Charlie says, with an edge to his voice.

Gil mutes the television.

Charlie goes to the refrigerator and pulls out a bottle of water. He drinks half of it, then pours some over his hands to wet his face. His focus is unsteady. Finally he sits down and says, “The man who fell from Dickinson was Bill Stein.”

“Jesus,” Gil whispers.

I feel myself go cold. “I don’t understand.”

Charlie confirms it by the look on his face. “He was in his office in the history department. Someone came in and shot him.”

“Who?”

“They don’t know.”

“What do you mean, they don’t know?”

A beat of silence passes. Charlie focuses on me. “What was that pager message about? What did Bill Stein want from Paul?”