The Season of the Hyaena (Ancient Egyptian Mysteries) (42 page)

Read The Season of the Hyaena (Ancient Egyptian Mysteries) Online

Authors: Paul Doherty

BOOK: The Season of the Hyaena (Ancient Egyptian Mysteries)

11.54Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

‘What was Yakoub doing in the city?’ I insisted.

‘My lord, all I know is that he and his companions were to take something from the treasury and give it to me to hand on to Lord Pentju. I repeat, I don’t know what it was.’

I glanced at the physician. ‘Do you, Pentju?’

He shook his head and drank deeply from his wine cup.

‘Why,’ I asked him, ‘did Nefertiti murder your family?’

‘As an act of revenge.’

‘Or a warning,’ I added. ‘She really wanted to get her hands on you,’ I insisted. ‘And you know the reason why, Pentju? She had heard rumours, as had Meryre and others, that Akenhaten might not be Tutankhamun’s father, but that you were. You confided such a secret to Djarka but not to me, true?’ I paused. ‘Most of what I now say is a matter of logic. This scandal is something Khufu never confessed but only hinted at. Ptah is the third God of the Memphis trinity. Hotep is his son. On Khufu’s scrap of paper, you, Pentju, become Ptah; Tutankhamun is Hotep: in other words, father and son.’

Pentju closed his eyes. ‘The truth, Mahu, is this. I loved my wife and children but I also fell in love with the Lady Khiya. Nefertiti, as you may recall, humiliated me at a banquet when I joked about her not producing a son. I plotted my revenge. I advised the Lady Khiya to take no more of the potions and powders sent by Nefertiti. I also gave her medicines to improve the fertility of her womb.’

‘Did you sleep with her?’

‘Yes, yes, I did. If the Divine One had discovered that, both I and the Lady Khiya would have suffered death and disgrace.’

‘But he never did. Is the Prince truly your son?’

‘Others would like to say so, but no: he is Akenhaten’s. Of course, when I stare at his face I sometimes like to think he is mine, yet I must not say that.’ Pentju shook his head. ‘Tutankhamun is of the imperial bloodline, True Pharaoh in nature and name. Nefertiti started those rumours. In time she would have tried to poison Akenhaten’s mind. Meryre and his fellow conspirators also found such stories useful.’

‘Of course.’ I breathed. ‘If they had been successful, they could have swept Tutankhamun aside as the illegitimate by-blow of some court physician; that’s why the dying Djoser referred to him as the true usurper.’

‘Khufu was the last of such conspirators.’ Djarka spoke up. ‘My lord, we trusted you but you promised Khufu life and limb. He was a snake in the grass. Whatever you promised, would the rest of the hyaenas keep faith? Wouldn’t Lord Ay’s spies have searched him out? Brought him back to Thebes for questioning?’

I filled both their cups. ‘So,’ I stared into the night, ‘everything makes sense. Khufu’s death, the whisperings of Meryre and Nefertiti’s plot. She must have realised her husband wished to abdicate. If she’d managed to retain power, she would have staged a mock public funeral for him using Yakoub’s corpse and encouraged those stories about Tutankhamun being illegitimate.’

‘Do you think the Lord Ay knows?’ Djarka asked. ‘Nefertiti was his daughter.’

‘Lord Ay may know,’ I replied, ‘but it is not in his interest to publicise such scurrilous rumours.’ I held my hand up, fingers curled. ‘Tutankhamun is the clasp which holds everybody and everything together. What we have discussed here should go no further.’

Djarka and Pentju glanced at each other and nodded in agreement.

‘Tell me,’ I sipped from my cup. ‘According to Khufu, Akenhaten, in one of his mad speeches, talked about the Watchers holding a secret. I don’t think he was referring to rumours regarding his son’s legitimacy. He didn’t know about them, and even if he suspected, he would have kept such a matter quiet: no man wishes to publicise that he has been cuckolded. So, what was he referring to?’

‘I don’t know,’ Djarka retorted.

‘But you had conversations with Yakoub?’

‘Yakoub brought physicians and doctors to purge Akenhaten’s body and soul, to purify his flesh from the drugs of madness which had turned his head and blinded his heart. They talked to him about the true nature of the One, the Hidden God. They may well have talked about the future.’

‘And?’ I asked.

‘My people come from the western hills of Canaan. The Apiru are a tribe of herdsmen, of farmers and shepherds. Many years ago they wandered into Egypt; some, like Great Queen Tiye, became more Egyptian than the Egyptians, assuming high office, deserting their own beliefs. Queen Tiye paid service to the Fertility God Min, though in her case it was pretence. She returned to the old ways and taught them to her son Akenhaten.’

‘What is this teaching?’ I asked.

‘That there is only One God, an invisible being who creates all things and sees all things.’

‘There’s more?’ I insisted.

‘Yes, my lord, there’s more: stories that the Apiru, particularly my tribe of Israar, have been chosen by this Invisible God, whose name cannot be mentioned, to produce a great Messiah whose rule will stretch from the great river to the far islands, who will bring all kingdoms under his way …’

‘And Queen Tiye believed her son Akenhaten was this Messiah?’

Djarka nodded. ‘Queen Tiye’s theories became known to the priests of Egypt. They also knew of prophecies about the Gods of Egypt being overthrown, of a Messiah coming, of a great nation being formed. Most of it is superstitious nonsense: that’s why,’ Djarka held his hands up, ‘on the one hand Tiye and Akenhaten pursued their vision, and on the other the priests of Egypt opposed it.’

‘Akenhaten truly thought he was the Messiah,’ Pentju commented. ‘In his madness he really believed he would found a new city and a new empire, that all men would come under his sway. The dream died and Akenhaten became absorbed with wine and the juice of the poppy.’

‘And Yakoub?’ I asked.

‘Yakoub told the truth,’ Djarka replied. ‘Akenhaten was not the One but only a precursor. There would be other precursors, heralds, prophets. A nation would be formed out of Egypt, but he must withdraw to allow this to happen.’

‘How true is this story?’ I felt as if a cold breeze had tingled the sweat on my back. ‘Is it nonsense? The babble of priests?’

‘It’s dangerous nonsense,’ Djarka declared. ‘My lord, for twenty years Akenhaten turned everything on its head: the Gods, the temples, the rituals of death, life and the hereafter. He brought Egypt to its knees. Many in Thebes think the nightmare is over. Akenhaten has gone and this city will be allowed to die. However, if they suspected, the likes of Horemheb and Rameses and the other powerful ones of Thebes, that only the plant had been cut but the roots still survived …’

I held my hand up for silence. ‘I follow what you say. First we have Akenhaten and his madness. He disappears, but Meryre picks up the standard and brings foreign troops into the Delta to threaten Egypt …’

‘So far,’ Djarka leaned across the table, ‘people think Akenhaten’s madness has died with Meryre. If they knew the full truth, they would lash out at my people.’ He spread his hands. ‘Now you understand why I’m so reluctant to speak, or to trust even you, Lord Mahu.’

I felt a chill of danger, yet secretly marvelled at Lord Ay’s cunning. Horemheb and the rest had to be assured, comforted that Akenhaten’s vision had died, but if they began to suspect that those same ideas were still flourishing … Tutankhamun was Akenhaten’s son; Lord Ay and others of the Akhmin gang were of Apiru descent.

‘There could be a blood bath.’ Djarka broke my reverie. ‘Horemheb and Rameses would demand that anyone of Apiru blood be removed from high office either in the council or in the temples. The Apiru, like the Hyksos of old, would be declared to be the enemy within, to be ruthlessly crushed or driven beyond Egypt’s frontier. My people would pay a heavy price, as would those who have any ties with us.’

‘Tell me more about these rumours,’ I urged. ‘About the Messiah.’

‘What I say,’ Djarka replied, ‘is the chatter round our camp fires, but they talk of an albino, a man with hair and skin as white as snow, of strange eyes. He will lead our people out of Egypt into a Promised Land.’

‘What Promised Land?’ I asked, though I suspected the answer.

‘Canaan, a land flowing with milk and honey. Can’t you see, my lord Mahu, the new dangers? If Horemheb and Rameses, and those who support them, suspected what we are discussing now, they would regard it as treason! Stories about how a tribe Egypt has housed and sheltered would one day bring chaos to the Gods of Egypt before marching across its frontiers to occupy a land which Egypt regards as its own …’ Djarka shook his head. ‘They would offer only one solution: the total destruction of every single member of our tribe.’

‘How much do you know of this?’ I turned to Pentju.

‘Djarka has told me what he has told you,’ Pentju admitted ruefully. ‘But there is one difference, my lord Mahu. I believe what he says: one day the prophecy will be fulfilled. After all,’ he smiled bitterly, ‘Akenhaten did overturn the Gods of Egypt. What happened once can happen again.’

I picked up my wine cup. How long, I wondered, would it take for Horemheb to reflect on what had happened? He and the other officers of the Imperial Army would regard the dreams of the Apiru as a serious threat to Egypt’s very existence. Egypt depended on Canaan for wood, wines and the rich produce of its river valleys.

‘Perhaps it will never happen?’ I whispered.

Djarka held my gaze.

‘Then pray that it doesn’t happen,’ I snapped.

‘It will happen, or so my people think. They talk of it constantly. How long before others realise that the blood of Akenhaten is Apiru? Tutankhamun is of the same, so it may all happen again.’

I put my wine cup down and rose unsteadily to my feet. I walked to the balustrade and stared down at the gardens. Here and there a pinprick of light glowed from the guard posts. I turned quickly and caught the stricken look in Pentju’s eyes; he had not told me everything.

‘You are right, Djarka,’ I murmured. ‘It’s not finished! It’s not finished at all.’

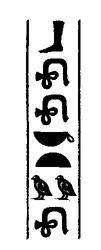

tcgar

(Ancient Egyptian for ‘enemy, rebel’)

(Ancient Egyptian for ‘enemy, rebel’)

The next morning I felt tired, my mouth still bittersweet with the taste of stale wine. I rose and checked on the Prince, already busy with his studies. He was kneeling before his table practising the writings of hieroglyphs. He smiled shyly at me, waving his hand. I returned to my own quarters and stayed there for most of the morning, busy with the scribes. I was disturbed by my captain of mercenaries but I yelled at him to go away. As usual, before noon, I rejoined the Prince. We often ate out on the balcony above the pleasure gardens. Djarka had been busy in emptying some of the treasures from the tombs: chairs and stools, tables and couches had been brought to decorate the young Prince’s chamber. I was particularly intrigued by two guardian statues standing on their pedestals. They were both carved from wood; the flesh part of each statue, a young man glaring fiercely, had been painted directly on to the wood with shiny black resin, the head cloths, broad collars, kilts and other details overlaid with gold on a linen base. The forepart of a bronze Uraeus had been attached to each statue’s brows; the lifelike eyes were created by carbuncle jewels inlaid with limestone and set in frames of gilded bronze. The statues were standing, one foot forward on their pedestals, almost identical except for their headgear. Djarka was busy directing workmen to inscribe on the front of the triangular kilt of each figure Tutankhamun’s name as proof of ownership.

‘I thought they were appropriate.’ Djarka smiled up at me. He pointed to the doorway. ‘They can stand on either side of that: they will protect the Prince as well as remind him of his father.’

The statues had the faces of young men, sloe-eyed, round-cheeked, works of superb craftsmanship. I walked around them. They stood about six foot three inches high; the inlaid precious metal caught the light and created an aura of gold around their faces.

‘Do you like them, Your Highness?’ I crouched down before Tutankhamun, who was gazing open-mouthed at these lifelike statues from that mysterious treasure hoard.

‘Do you like them, Your Highness?’ I repeated.

‘Of course he does,’ Djarka interjected. ‘Look at their faces. Don’t you see a likeness between the carvings and His Highness?’

I did: the same youthful chubbiness, the wide-eyed stare. ‘Pentju,’ Djarka added, ‘and the craftsmen here, believe Pharaoh had these statues made as gifts for his son, to act as guardians. It’s a common enough practice.’

Other books

Sticks and Stones by Ilsa Evans

The Sheep Look Up by John Brunner

Eagles at War by Boyne, Walter J.

Portraits by Cynthia Freeman

Random Acts Of Crazy by Kent, Julia

Saving The Alien Star Lord (Alien SciFi Romance) by Meg Ripley

The Loner by Joan Johnston

Peaceable Kingdom (mobi) by Jack Ketchum

First Night: by Anna Antonia

The Sunlight Dialogues by John Gardner