The Season of the Hyaena (Ancient Egyptian Mysteries) (45 page)

Read The Season of the Hyaena (Ancient Egyptian Mysteries) Online

Authors: Paul Doherty

BOOK: The Season of the Hyaena (Ancient Egyptian Mysteries)

13.49Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

‘Speak! Speak!’

The man spat at me. I drove my knee into his face, crushing his nose.

‘Speak!’ I repeated.

Again the man tried to spit, but this time his lips only spluttered blood. I withdrew. My mercenary captain began to skin him alive, beginning with his arms. The man shook and screamed. I returned and stood over him.

‘Speak,’ I urged, ‘and death will come swiftly. Stay silent or lie and each day my captain will strip part of your skin.’

Another hour passed before the man broke. Gabbling and stuttering, he could tell me very little. Once he had been a soldier, a veteran in the regiment of the Aten, and later body servant to the Lord Meryre. He had not gone to Buhen and was surprised by the reappearance of Meryre and others of his circle who had crept back in disguise into the City of the Aten. They brought a hideous tale. A bloody massacre had occurred out in the eastern desert: Lord Tutu and hundreds of their followers had been killed on the orders of Lord Ay, who had sent chariot squadrons and troops of mercenaries allegedly to provide protection and safe passage through the desert and across Sinai. According to our prisoner, Meryre and about a dozen soldiers had escaped by fleeing across the desert away from the oasis. Using what wealth remained, they had travelled back into the Delta before moving to the City of the Aten, sheltering in the slums south of the city.

I immediately ordered my police and mercenaries to search there, but they returned empty-handed; they had found nothing except deserted hovels, whilst those who lived nearby had heard and seen nothing at all. The prisoner was only a soldier, paid by the Atenists to carry out my assassination.

‘Why me?’ I asked. ‘Why did Lord Meryre return here? I had no hand in the massacre.’

‘He holds you responsible,’ the assassin replied. ‘He thought it would be easier here. He has a blood feud with you, blood for blood.’

For two days I questioned that prisoner. I didn’t even allow Djarka to approach him. I alerted Nebamun and his chariot squadrons on the clifftops. Meryre, however, proved too cunning and slipped away.

Eventually I was satisfied. I ordered my captain to cut the prisoner’s throat to give him speedy release and immediately made the decision. Urgent letters were drawn up and dispatched to the Lord Ay in Thebes. My chief messengers were entrusted with the task. Ay should be warned that his massacre was now well known. I closed one letter reminding him that he might well reap what he had sown. I also decided to go out to the eastern desert to visit the Valley of the Grey Dawn for myself. Colonel Nebamun objected, as did Djarka, but I was insistent. The Prince would be moved into the care of Pentju, whose residence would be ringed by every available soldier. They would guard the Prince and Ankhesenamun whilst Djarka, myself and Mert, together with the sand-dwellers, would visit the Valley of the Grey Dawn. I demanded twenty of Nebamun’s chariots and the best guides and scouts he could provide to accompany half my mercenary corps. Nebamun reluctantly accepted my orders, though Djarka was full of protests.

‘If you leave this city,’ he objected, ‘something might happen. These rumours,’ he protested, ‘about the City of the Aten being deserted. They have turned ugly.’

‘Do you think they are connected with Meryre’s return?’ I asked.

‘Of course! We should forget the Valley of the Grey Dawn.’ Djarka stepped closer. ‘We should forget this city. It is time, my lord, you returned to Thebes.’

I shook my head. ‘Time enough,’ I whispered. ‘I must visit that valley.’

‘Why?’ Djarka insisted.

‘I don’t really know.’ I smiled. ‘But when I do,’ I clapped him on the shoulder, ‘you will be the first to know.’

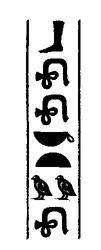

an-cc-kek

(Ancient Egyptian for ‘dark valley’)

(Ancient Egyptian for ‘dark valley’)

Preparations for our expedition dominated the next few weeks. We would have to face the savage heat in an arduous journey across arid sands, where wells and springs were scarce and jealously guarded by fierce tribes of desert wanderers. Laden with bribes, envoys were sent out to treat with these. Safe passage was assured, expert scouts hired, sturdy donkeys bought, water skins and provisions carefully assembled.

Only veterans used to the searing heat and desert warfare were selected. Colonel Nebamun promised to supervise everything whilst I concentrated on the reports coming in from my spies in the city, who all chanted the same hymn, of a growing disquiet, a grumbling malice against the palace as well as the Royal Circle in Thebes. Powerful merchants and nobles were hiring retinues, whilst our patrols along the river often discovered arms being brought in, yet for every dagger found, five remained untraced. None of my scribes could discover the source of this growing unrest. Meryre’s agents had spread fear, moving like shadows in the dead of night. They had sown their crop and left us to reap the harvest. The news of the hideous massacre somewhere out in the eastern desert was openly discussed in the beer shops and marketplace. Ugly rumour drifted like curls of black smoke, yet there was little I could do to prevent it. Chariot squadrons were brought into the city. The palace was fortified. Masons and builders strengthened its walls and gateways. Watchtowers were set up. All roads leading to the palace, as well as its inner precincts and courtyards, were heavily patrolled, both day and night. No one was admitted unless they carried a document sealed with my own cartouche and knew the password for that particular watch.

Nebamun, Djarka and I pored over maps of the city, organising how, if necessary, the palace could be evacuated, and the Royal Household safely escorted down to the war barges; their captains were already under orders to leave at a moment’s notice. Nebamun wanted to send messengers to Memphis and Thebes asking for reinforcements, even permission to withdraw. I told him I would take responsibility, leaving the grizzled veteran to glower angrily back. Journeys into the city were no longer pleasant excursions. The Royal Household was confined to the palace gardens and courtyards. If I, or any of my officials, left the palace, we were always accompanied by a military escort. The Prince seemed unperturbed by these preparations; I would invite him for a game of Senet or, early in the morning, take him down to the courtyard to practise archery.

Tutankhamun was playful and vigorous enough, though he constantly favoured his left side; at times he complained about aches in his legs and arms. Occasionally, he would sit as if drugged, a dreamy look in those doe-like eyes, a smile on his half-open lips, as if he were savouring some secret joke or could see something I couldn’t. My suspicions that he was simple, of vacuous wit, would re-emerge, only to be rudely shattered by an abrupt change in mood. Like a scribe learning the law, Tutankhamun would crouch before me and closely question me about his father, the city we lived in, and above all, the worship of the Aten. He was aware of the Apiru and the stories of the people of Israar, and I began to regret Djarka’s influence over him. Tutankhamun also became sensitive to my moods. If he believed he was annoying me, he would swiftly change the topic. I found him quick-witted, with a ready humour. I called him Asht-Heru, Many-Face, because he proved to be such an able mimic. I would roar with laughter as Tutankhamun imitated Colonel Nebamun and strode up the room, shoulders back, chin tucked into his chest, glaring at me from under his eyebrows, shouting in a deep voice. Abruptly he’d change, becoming a lady of the court. Only once did such mimicry cause a ripple of fear. Tutankhamun seemed to have little love for the priests, the Rem-Prieta, or Men of God. He could mimic their pious looks, their sanctimonious walk, their love of being seen to pray publicly, and the way they sang, more like a whine through their nose. On this occasion he must have caught my sad glance because he came running up.

‘Uncle Mahu! Uncle Mahu! You are not laughing?’

‘Oh, you are funny enough!’ I clasped his hands. ‘It’s just that I have thought of something.’ I didn’t tell him how, as a young man, Akenhaten had loathed and mocked the priests of Amun. Tutankhamun was intelligent enough to realise this mimicry did not please me, and quickly reverted to imitations of Nakhtimin and Djarka.

I used that time of preparation to study the Prince more closely. I dismissed my secret doubts that he was Pentju’s son. The more I watched him, the more I could see Akenhaten. Like his father, Tutankhamun was dedicated to a physical purity. If he spilt beer on his robes, he immediately changed, and during the day would often demand perfumed water to wash his hands. He loved to be anointed with oil and perfume. I put this down to Ankhesenamun’s influence; she now seemed to dominate his days.

In the main, Tutankhamun was kind and gentle. He often expressed regret at the two tortoises he had killed, yet that streak of angry malice could still surface. I’d catch occasional glimpses of this: an irritation with a servant, or shoving aside a piece of duck not cooked to his taste. The more serious incident occurred a week before we left. I was in the garden, dictating to my scribes. The laughter of Tutankhamun and the ladies of the court was abruptly replaced by loud screams. I hurried out of the pavilion across to the small palm grove where Ankhesenamun, Amedeta and Mert were resting in the shade. Tutankhamun, a thin cane in his hand, stood over a cowering servant. He was berating him, then he brought the rod down, lashing the unfortunate’s head and shoulders. Other servants stood by, watching helplessly. As I approached, Ankhesenamun stopped laughing and called out to Tutankhamun to stop, but the boy, dancing with rage, brought the cane down time and time again, drawing blood from the man’s cheek and lips. I hurried over and grasped the cane. Tutankhamun would not let go. His face was no longer serene but blotched with rage, eyes glaring, lips twisted, a slight froth staining the corner of his mouth.

‘My lord,’ I urged, ‘let go.’

‘Uncle Mahu! Be gone! This

smett

,’ he spat out the word for slave, ‘I caught in the act of

ta-ta

.’ He glared at the miscreant. ‘He was fondling himself to bring his own seed. I caught him there behind the bush. He has polluted himself. He has defiled his body in my presence.’

smett

,’ he spat out the word for slave, ‘I caught in the act of

ta-ta

.’ He glared at the miscreant. ‘He was fondling himself to bring his own seed. I caught him there behind the bush. He has polluted himself. He has defiled his body in my presence.’

I pulled the cane from Tutankhamun’s hand.

‘How dare you?’ Tutankhamun yelled back. ‘You, too, are a

smett

, Baboon of the South! You are defiled.’ He stood, hands clenched, quivering with rage. I glanced up. Amedeta and Mert, together with the servants, had fled. Ankhesenamun was staring coolly at me, her beautiful face slightly turned, clearly enjoying the confrontation. Tutankhamun seized the opportunity to run at me, fists flailing. I grasped his arms, even as I recalled his father’s hideous rages.

smett

, Baboon of the South! You are defiled.’ He stood, hands clenched, quivering with rage. I glanced up. Amedeta and Mert, together with the servants, had fled. Ankhesenamun was staring coolly at me, her beautiful face slightly turned, clearly enjoying the confrontation. Tutankhamun seized the opportunity to run at me, fists flailing. I grasped his arms, even as I recalled his father’s hideous rages.

‘My lord, you are unwell!’ I snapped.

‘I am the Leopard God,’ Tutankhamun hissed. ‘I am Horus in the South, Horus in the Ground, Horus in the Spirit Soul, Horus of the Red Eyes.’ He tried to break free, as if to pursue the servant, who had crawled away on his hands and knees. ‘I am Lord of the Two Lands.’ He turned back to me. ‘I live in the truth.’

I shook him, slapped him gently on the cheek. In the twinkling of an eye the rage disappeared, and both face and body sagged. I let go, and he ran across to Ankhesenamun, crouching for shelter in the crook of her arm, thumb to his mouth.

‘He polluted himself,’ he whispered. ‘Only a Prince can bring forth his own seed.’

Ankhesenamun’s hand hung down just above the young boy’s crotch. I wondered what teaching she had provided.

‘Does this happen often?’ I asked.

‘Ask your spy Djarka.’

‘I do. He’s not a spy. He protects the boy.’

‘For how long, Uncle Mahu?’ Ankhesenamun’s eyes rounded in mock innocence. ‘How long will you guard us? Weeks slide into months, and months into years. My husband to be,’ eyes still watching me, she turned and lightly kissed Tutankhamun’s forehead, ‘will one day have to emerge and walk in the light of the sun. He cannot stay hidden for ever.’

‘When the time comes.’

‘The time is already here,’ she retorted, leaning forward. ‘I have heard the rumours. The city is unsafe. Why do you go out into the desert, Uncle Mahu?’

‘You know why, my lady. I am sure your grandfather has written to you, whilst you must have spies amongst my scribes. The Atenists were massacred out in the eastern desert. Lord Meryre escaped and attempted to take my life.’

Ankhesenamun smiled thinly. ‘Grandfather always said Meryre was a fool.’

‘A dangerous one,’ I added.

Other books

Battles Lost and Won by Beryl Matthews

Forbidden Fruit by Erica Spindler

Autumn in the Vineyard (A St. Helena Vineyard Novel) by Adair, Marina

Two Wild for Teacher: Lone Star Lovers, Book 6 by Delilah Devlin

Gazelle by Bello, Gloria

Lethal Temptations (Tempted #5) by Janine Infante Bosco

Highly Strung by Justine Elyot

Black Daffodil (Trevor Joseph Detective series) by John, Katherine

Blink of an Eye by Keira Ramsay

The Pinballs by Betsy Byars