The Season of the Hyaena (Ancient Egyptian Mysteries) (53 page)

Read The Season of the Hyaena (Ancient Egyptian Mysteries) Online

Authors: Paul Doherty

BOOK: The Season of the Hyaena (Ancient Egyptian Mysteries)

10.7Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Once Pentju’s questions were answered, he would go back to his drinking. He had grown obese and red-faced, and more often than not he was drunk. He could still be a skilled physician and a witty companion, but he insisted on sleeping the day away and drinking through the night. He confided in me that when darkness fell, the ‘demon thieves’ sprang out of the darkness and plagued his soul.

‘They wait for me,’ he whispered, tapping his fleshy nose. ‘I see them lurking in the cypress groves with the fires of hell burning all around.’

Djarka lost patience with him and declared he was mad. I believe he was as sane as any of us. Like me, he was plagued by ghosts from the past, and not all such ghosts are easily exorcised.

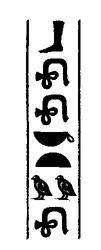

Shta-i

(Ancient Egyptian for ‘the Secret Place’)

(Ancient Egyptian for ‘the Secret Place’)

In the first week of the month of Thoth – the eighth year of Tutankhamun, Lord of the Two Lands, Mighty Bull, Most Fitting of Forms, Horus in the South, Horemheb and Rameses visited me. I truly thought I would never see this precious pair again. Yet they came swaggering through the main gates, splendid in their robes, all agleam with their medallions, collars, brooches and rings. Outside the gate their staff officers unhitched their chariots, chattering and laughing as they led them off into the green coolness of a palm grove. Horemheb looked a little plumper, a roll of fat beneath his black button eyes, slightly jowly, though his body was still hard and muscular. Rameses was more wrinkled but lean as ever, eyes full of malice, that smirk on his thin lips; he still reminded me of a vicious greyhound. They were pleasant enough, clasping my hands, ordering a servant forward with gifts, joking with Pentju and Djarka. Rameses mischievously asked whether Sobeck, my ‘constant visitor’, was present.

I just smiled.

‘You haven’t come about my health,’ I suggested. ‘So you have come to plot.’

They did not disagree. We met behind closed doors in the Blue Lotus Pavilion. After a few pleasantries Rameses threw down his whisk. I was highly amused by it. The whisk was sky blue, with a golden lotus on the handle; more suitable for a lady of the court rather than a high-ranking officer of the Imperial Staff.

‘Are you enjoying retirement, Mahu?’ he sneered.

‘You mean my exile?’

‘Your exile.’ Rameses smirked. ‘You must miss the heavy perfume of the court.’

‘I miss neither that nor your stench.’

‘Mahu, Mahu, you don’t miss your friends?’

‘I miss the smiles of Pharaoh. May he live a million years and enjoy countless jubilees.’

Rameses and Horemheb hastily agreed.

‘The Divine One also misses you.’

‘How do you know that? I understand very few people are allowed to see him.’

‘We do meet him at the Royal Circle,’ Horemheb intervened.

‘And how do you find him?’

‘Quiet, serene.’ Horemheb shrugged. ‘The Lord Ay is his mouthpiece.’ I sensed the hidden tension, a shift in Horemheb’s eyes. Rameses was studying me curiously, head slightly to one side, puckering his lower lip between finger and thumb.

‘I understand,’ I broke the silence, ‘that you, General Rameses, have been very busy in your studies about the history of the Apiru.’

‘You know why.’ Rameses picked up the flywhisk. ‘I’m sure your friend Sobeck has told you everything, so let’s be blunt, Mahu.’

‘My lord Rameses, that would be a change.’

‘Akenhaten may still be alive. Meryre is definitely hiding in Canaan with the other heretics, stirring up trouble.’

‘But he’s not with Akenhaten?’ I asked.

‘You mean the madman.’

‘We all supported him, General Horemheb.’

‘For a while, but that’s not why we are here.’ Horemheb cleared his throat. ‘My lord Mahu, would you like to return to power?’

‘Why?’ I replied. ‘To be your spy?’

‘Oh come, come,’ Rameses protested.

‘Oh come, come, General Rameses. Why else are you visiting me? It’s certainly not because of my lovely eyes and generous character.’

‘We would like to see you appointed as Overseer of the House of Envoys,’ Horemheb murmured. ‘To lead a diplomatic mission to the Hittites. You are sly enough to assess their power, cunning enough to judge if they are a real danger to us.’

‘And report back to you, as well as Lord Ay?’

‘Of course,’ Rameses agreed.

‘You want me to go to Canaan to spy, but you are hoping that Akenhaten will show himself to me; for some strange reason he had a special liking to me. And if he does, you’ll kill him.’

Rameses smiled.

‘Do you think,’ I continued, ‘Lord Ay would embrace me and give me the rings of office? He’d realise you wanted me back as your spy.’

‘You’re our friend.’

‘Since when?’

Horemheb laughed. ‘Very good, my lord Mahu. Huy and Maya would welcome you back.’

‘For what? To keep a watch on Lord Ay?’

‘Let’s cut to the marrow of the bone.’ Horemheb shifted forward. ‘The Divine One himself wishes your return.’ He smiled at my surprise. ‘Our Pharaoh is almost a young man, of seventeen summers. I find him strange. I don’t think his health is good, in either body or soul. You know that, Lord Mahu. You lived with him when he was a child. He is given to outbursts. In the last few months he has increasingly demanded in a pained voice, “Where is Uncle Mahu?”’

‘Why now?’ I asked.

‘Why not?’ Rameses retorted. ‘Perhaps he has done it before, though in private. He wants you and Pentju to return. Oh, by the way, how is the toper?’

‘As always, General, a better companion than you. So,’ I drew myself up, ‘the Divine One wishes me to return. A wish supported by new-found friends. Well, well!’ I leaned back. ‘My two lions, you have surprised me! Do you really need me, Horemheb? Don’t forget you’re married to Mutnedjmet, sister of Nefertiti!’

‘My wife is as different from her,’ Horemheb snapped, ‘as gold is from sand. She has nothing in common with her father, that mongoose of a man, or her scorpion sister. She does not like her father.’ He shrugged. ‘That was the beginning of our friendship.’

Horemheb plucked at the tassels of his robe.

‘I want you back, Mahu. I want you in charge of the House of Envoys; I want to find out what is happening in Canaan. Lord Ay spies on me and I on him. Sobeck must have told you about the presents and the money he has sent to the Mitanni. At first, I thought this was just policy, to keep the Hittites contained, but there’s more. He has been searching for the Lady Tahana.’

My heart skipped a beat.

‘She was principal lady-in-waiting to Khiya, Tutankhamun’s mother. She and her husband mysteriously left the City of the Aten and returned to the Mitanni court around the same time the plague struck.’

‘Why should he be searching for her?’ I asked.

‘We don’t know. Earlier this year, during the last month of the Season of the Planting, General Nakhtimin and a squadron of troops sailed up the Nile for a meeting with a Mitanni envoy. We don’t know why they met or what was agreed. They returned by night to Thebes.’ He paused. ‘According to my spies, Nakhtimin brought back a man, his face covered by a jackal face-mask. I also heard reports of the same man being imprisoned in the old House of Residence, where we all trained as Children of the Kap.’

I couldn’t hide my consternation. ‘Was it Akenhaten?’

‘No.’ Horemheb shook his head. ‘The individual was young, we could tell by his belly and legs. I have tried everything,’ Horemheb confessed, ‘to discover what happened. Nakhtimin’s troops closely guarded that part of the palace. In recent months they have withdrawn, which means the young man has either gone or died. Now,’ Horemheb scratched his head, ‘I’m afraid, Mahu. What is Ay plotting? Will something happen to Tutankhamun, and would Ay claim the throne? So,’ he smiled, ‘if the Divine One and the Royal Circle ask you to return, will you agree?’

‘I will think on it.’

‘And if you return, will you be our ally, not our spy?’

‘I will think on it.’ I made to rise.

‘You don’t seem worried about the Divine One.’ Horemheb clasped my wrist. ‘He was your charge.’

I broke from his grip. ‘That was in the past, General. I cannot be held responsible for what I have no power over.’

I recalled Tutankhamun’s gentle, almond-shaped eyes, his serene face.

‘You do care, don’t you?’ Horemheb asked.

He felt amongst his robes, drew out a leather pouch and shook out the contents: an exquisite strip of gold depicting Pharaoh wearing the war crown of Egypt, smiting the head of an enemy in the presence of the War God Montu, behind him the Goddess Nepthys.

‘Lord Ay hired a goldsmith to fashion this for him; an apprentice in the shop made a fair copy.’

I examined the gold strip carefully. On closer inspection it was cruder than any original. The Pharaoh was Tutankhamun, no more than a boy, but from the hieroglyphs on the band of gold, I realised that Ay was the God Montu and Ankhesenamun the Goddess Nepthys.

‘Ay made that for his own personal use.’ Horemheb took it from me. ‘He is becoming arrogant. He sees himself as a God, the master of the Pharaoh.’

Horemheb was not lying. No Egyptian would ever dream of fashioning such a scene. Pharaoh paid service to no one but the Gods; he was their equal, the living incarnation of their will.

‘Now we know there is something wrong with Tutankhamun.’ Rameses got to his feet. ‘Can you imagine, Mahu, Akenhaten bowing to anyone? Is Ay abusing his position? Are there secret ceremonies at the court where Ay and his granddaughter dress up as gods and make Pharaoh bow before them? Now, you think!’

For the rest of that day, I sat in the pavilion, my mind a whirl. Servants brought me food and drink. Why was Ay hunting for some young man amongst the Mitanni? What was he planning? Darkness fell. The evening breeze was refreshing, and through the half-open door I could see the servants. Djarka came over. Did I want to join him and his family for supper? I declined, and he wandered off. A short while later Pentju arrived, followed by his servants carrying a jug of wine and two goblets.

‘I heard about the visit of the mighty warriors.’ Pentju sat down on the cushions. ‘Did they ask after me? I suppose they didn’t.’

‘You need a bath,’ I retorted. ‘And a shave.’

‘What I need, Mahu, is a goblet of wine and a young maid. I am going to make a nuisance of myself until you tell me what those two cruel bastards came here for.’

I told Pentju how they wished me to return to court. I mentioned the House of Envoys and, only the Gods know the reason, I told him about Ay, his dealings with the Mitanni and that strange prisoner Nakhtimin had brought back from the Delta. Pentju sat, all colour draining from his face, mouth open, eyes staring, as if he’d been visited by some horror in the night. Perhaps I’d drunk too much myself, for I pressed on with the story. The goblet slipped from Pentju’s hand and he began to shake like a man in a fit. I called his name, but he stared as if he couldn’t see any more. A strange sound bubbled at the back of his throat. The shock sobered me up. I left the pavilion, shouting for help. When I returned, Pentju was convulsing on the floor, his muscles rigid. He had vomited, and for a moment I thought he was choking. A leech arrived and made sure that Pentju’s throat was clear, then placed a leather wedge between his teeth and shouted for blankets.

I sent a messenger to Sobeck to ask him to hire the best physicians of the mouth, heart, stomach and anus. They diagnosed some fit brought on by a fever of the mind. In truth, like all doctors they were useless. They grabbed my silver and informed me that Pentju should have bed rest and no wine. I could have reached the same conclusion, so I sent them packing through the gate. When Sobeck learned what had happened he just shook his head, whistled under his breath and cursed his spies for failing him. He confessed he knew nothing about what Horemheb and Rameses had told me. At the moment there was little I could do with such information. I was too busy nursing Pentju, as well as curious to discover why my words had provoked such a powerful reaction. Some of the physicians believed Pentju’s ailments were the work of a

gesnu

– an evil being or demon. I heartily agreed. It was a fitting description for Ay and his Akhmin gang.

gesnu

– an evil being or demon. I heartily agreed. It was a fitting description for Ay and his Akhmin gang.

Other books

Logan Trilogy by William F. Nolan, George Clayton Johnson

Doctor Who: Marco Polo by John Lucarotti

Dead Things by Stephen Blackmoore

Some Kind of Magic by Weir, Theresa

Death by the Book by Deering, Julianna

Veil of the Dragon (Prophecy of the Evarun) by Tom Barczak

All Things Undying by Marcia Talley

The Billionaire's Desire (A Billionaire BWWM Steamy Romance) by Mia Caldwell

One Night for Love by Maggie Marr