The Season of the Hyaena (Ancient Egyptian Mysteries) (55 page)

Read The Season of the Hyaena (Ancient Egyptian Mysteries) Online

Authors: Paul Doherty

BOOK: The Season of the Hyaena (Ancient Egyptian Mysteries)

7.3Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

In a word, Pentju was appointed Royal Physician and I was to become Overseer of the House of Envoys, with responsibility for foreign affairs. All the time I watched Tutankhamun staring beatifically at me. Now and again in his excitement he would turn to Ankhesenamun. She slouched on her throne, one pretty sandalled foot tapping ever so imperiously. I would wink at Tutankhamun or slightly raise my hand. Beside me, Pentju glowered as Ay, the Great Mongoose as we now called him, turned to the other business. Most of it was mundane, the greater part being the situation in Canaan. Its petty princelings still squabbled; the real danger were the Hittites, who were now a major threat to Egypt’s allies in the region, the Babylonians and the Mitanni. Horemheb and Rameses sang the same old hymn, the need for military intervention. Ay was not so eager to contradict them, the question being when and how. The lions of the desert seemed satisfied with this and eventually the meeting ended.

Pentju and I were brought before the Royal Throne. Ankhesenamun indulged in her usual flirtations, leaning forward allowing her gold robe to hang loose, exposing her breasts, the nipples of which were painted silver. She had that questioning, innocent look as if wondering where we had been all this time; she was most effusive, caressing my cheek or patting Pentju’s balding head. Her touch was cool, her perfume the most expensive Egypt could provide, the juice of the blue lotus. She was most solicitous, anxious about our well-being. We both could tell from her eyes that the royal bitch was laughing at us. Tutankhamun, however, was delightful, so pleased to see us he almost forgot court protocol and couldn’t sit still with excitement. He gave each of us a gold collar, and leaned closer so that he could fasten mine round my neck, then he brushed my cheeks with his lips and called me Uncle. Ankhesenamun, meanwhile, sniggered behind her hand.

Ay coughed loudly to remind Tutankhamun of court etiquette. The young Pharaoh recalled himself and tried to keep his face straight, but the effort was useless. He returned to calling me Uncle, saying how much he had missed both me and Pentju, how we must come fishing and fowling with him or, perhaps, take his war chariot out into the eastern desert. He seemed healthy enough, bright-eyed and plump-cheeked, though his body was manifesting some of his father’s characteristics: a slightly pointed chest, broad hips, long fingers and toes, legs, thighs and arms rather thin. He was also experiencing some discomfort when he moved.

Once the audience finished, some of the Royal Circle approached to congratulate us: the usual smiles and handshakes, shoulders being clasped, promises made, invitations issued. They lied to me and I lied to them, but that was the nature of the court. I recalled the old proverb: ‘Put not your trust in Pharaoh, nor your confidence in the war chariots of Egypt.’ I only hoped Pentju would not provoke a confrontation with the Lord Ay.

Later that day there was a great feast in the Silver Hawk Chamber at the other side of the palace. Only members of the Royal Circle were invited. Long tables covered with shimmering Babylonian muslin were placed before each guest, bearing jewel-encrusted goblets and platters of pure silver. Around the room stood great terracotta jars of wine for servants to keep the goblets ever brimmed, whilst others served shellfish sprinkled with spices, fried lotus in a special sauce, and a range of baked meats: antelope, hare, partridge, calf and wild ass. Pyramids of fruits were set before us: grapes, melons, lemons, figs and pomegranates. In the centre of the chamber a small orchestra with harps, drums and other instruments played soft music under the watchful eye of the eunuch who marked time with a reed. A place had been set for Pharaoh and his wife, who were expected to appear later in the proceedings, though they never arrived.

Whilst the rest got drunk, I watched Ay, who seemed distracted as a stream of servants came and went with messages. Eventually agitated, he got up from his table and left. A short while later one of his servants came and whispered to Pentju and me that we should withdraw. He led us hastily along beautiful galleries and passageways, across fragrant gardens and courtyards where fountains supplied their own music. At last we reached the heart of the palace, the Royal Apartments. Ay was waiting for us in the antechamber. Nakhtimin and some of his senior staff were also present. From the chamber beyond I could hear Ankhesenamun weeping loudly.

‘You’ve been given the reason for your return,’ Ay declared. ‘In truth there were two reasons; now you will see the second.’

He snapped his fingers, the great double doors swung open and we followed Ay into a long decorated chamber, poorly lit by oil lamps, with a great open window at the far end. In the centre of the room, dressed only in a loincloth, squatted Tutankhamun, a wooden lion in one hand, a toy antelope in the other. He placed these on the floor, pretending the lion was chasing the antelope. I brushed by Ay and, followed by Pentju, hurried across.

‘My lord.’ I squatted down. ‘What is the matter?’ I sniffed and glanced down: the loincloth was soiled; Tutankhamun had wet himself. ‘My lord,’ I repeated, ‘are you well?’

Tutankhamun lifted the wooden toys and smacked them together. Pentju cursed quietly. Tutankhamun seemed totally unaware of our presence.

‘Gaga.’ He lifted the wooden lion and sucked on it as a baby in a cot would. Pentju began whispering the words of a prayer. I stared in disbelief: the Pharaoh of Egypt, the Lord of Two Lands was not insane, but a helpless baby. I tried to touch him but he flinched, absorbed by the toys in his hands. Footsteps echoed behind me.

‘How long?’ I asked.

‘The attacks are not frequent,’ Ay replied, ‘but when they occur they are intense. High excitement or confrontation seems to cause them. Sometimes he is like this, other times argumentative and very aggressive.’

We waited for an hour before Tutankhamun began to relax and grow heavy-eyed. We let him sleep on the floor, cushions and blankets being brought to make him as comfortable as possible. Ay agreed to meet us in the antechamber. He wanted Nakhtimin to stay but Pentju insisted he leave. I had never seen the physician so cold and so implacable.

I shall never forget that night. The window behind Ay opened on to darkness as deep as that of the Underworld. Not one star, not one blossom of the night could be seen; there was no sound, as if the calls of the birds, the night prowlers and the creatures of the Nile had been silenced. Only three men, seated in a chamber, on the verge of the confrontation both Pentju and I had been praying for.

‘My son?’ Pentju began.

‘The Divine One …’ Ay intervened.

‘He must wait,’ Pentju rasped. ‘My son, the child of the Lady Khiya, you bribed the Mitanni to hand him over.’

‘I don’t …’ flustered Ay.

‘You do,’ Pentju cut in. ‘He’s dead, isn’t he? Why did you bring him here?’

‘I wanted to discover who he really was,’ Ay retorted.

‘You knew who he was.’

‘He looked so much like his half-brother, the Lord Pharaoh.’ Ay’s voice was kindly, but the look in his eyes was chilling. I realised what he’d intended.

‘Did you?’ I gasped. ‘Yes, you did, didn’t you? You seriously considered replacing one for the other, that’s why you brought him here. They would look so alike! Very few people see Tutankhamun, and only then from afar.’

Ay stared coolly back.

‘You said he

looked

?’ Pentju kept his voice steady. ‘So he is dead?’

looked

?’ Pentju kept his voice steady. ‘So he is dead?’

‘He was sturdy,’ Ay replied. ‘A good man, Pentju, intelligent and charming. He died of a fever—’

Pentju lunged forward; I pulled him back.

‘He died of a fever.’ Ay remained calm. ‘You, however, think I murdered him, that I brought him here to be killed, true?’ He played with the ring on his finger. ‘I am a hyaena,’ he confessed. ‘I kill because I have to, because I don’t want to be killed myself.’

‘You hated Khiya,’ Pentju yelled.

Ay shook his head. ‘I did not hate her.’

‘She displaced your daughter.’

‘Nefertiti was a fool,’ Ay snarled. ‘She was arrogant, she really believed she was Pharaoh’s equal. We are responsible for our children, but not for their mistakes. As for you, Pentju, I shall never reveal what I really intended with your son, but I am innocent of his blood. I will take a solemn oath.’

Pentju sneered in reply.

‘I can produce a physician from the House of Life who will corroborate my story. If I had murdered the boy, his corpse would have been consigned to the crocodile pool, I would have denied meeting him.’

‘You have the corpse?’ Pentju exclaimed.

‘Your son’s body was hastily embalmed in the

wabet

, the Pure Place in the Temple of Anubis, and buried according to the rites in the Valley of the Kings.’

wabet

, the Pure Place in the Temple of Anubis, and buried according to the rites in the Valley of the Kings.’

‘Did he suffer?’ Pentju asked. ‘Did he talk or ask about me?’

‘He was well treated,’ Ay whispered. ‘I would have taken Nakhtimin’s head if he hadn’t been. True, his face was hidden by a mask, but that was for his own safety. He was placed in the House of Residence and shown every courtesy.’ Ay sighed. ‘He truly believed he was the son of a Mitanni nobleman, that his parents had died when he was a boy. He was training,’ Ay paused, ‘strange, he was training to be a soldier, but he confessed he had a deep interest in medicine.’

‘What did you tell the Mitanni?’ I asked.

‘Quite simple. I told them he might be my son,’ Ay smiled, ‘and that, either way, he would receive good training in our barracks and the House of Life.’

Pentju, head bowed, was sobbing quietly.

‘I made a mistake,’ Ay confessed. ‘The young man was used to the clean air of the highlands of Canaan. The Nile has its infections and often claims its victims, you know that, Pentju. He fell suddenly ill and slipped into a fever. No one could save him. So, Pentju, I have your son’s blood on my hands, I recognise that, as I do that you are my enemy. I realise that if the opportunity ever presents itself, you will kill me.’

‘I’ve always been your enemy,’ Pentju answered. He raised his tearful face. ‘Lord Ay, one day, if I can, I shall kill you.’

Ay blinked and looked away. He was a mongoose of a man, but I was convinced he was not lying, nor was he alarmed by Pentju’s threats.

‘I am not frightened,’ Ay replied, his face now only a few inches from Pentju’s. ‘The only difference between you, Pentju, and the rest is that you have been honest.’

‘So why not kill us?’ I asked. ‘Why not now?’

Ay leaned back. ‘For the same reason I didn’t years ago. You have powerful friends. Meryre, Tutu and the rest deserved their fate, but Horemheb and the others would baulk at murder, at the illegal execution of two old comrades, former Children of the Kap.’

‘Secondly?’ I insisted. ‘There is a second reason?’

‘The Divine One himself, when in his right mind, would have objected, and thirdly,’ Ay coolly added, ‘I need you to protect him, to see if you can do something to bring his mind out of the darkness.’

‘Where is my son?’ Pentju demanded.

‘He is in a cave, isn’t he?’ I asked. ‘One of those secret ones you’ve quarried in the Valley of the Kings?’

‘To house the dead from the City of the Aten,’ Ay agreed, ‘as well as for eventualities such as this. You will be taken there, I assure you.’

Pentju put his face in his hands.

‘And now,’ Ay placed his hands together, ‘what shall we do with our Pharaoh, who has the body of a young man and, sometimes, the mind of a babbling infant? You must help him, Mahu, as much as possible.’

‘Why?’

‘To put it bluntly, my granddaughter, Ankhesenamun, must conceive a son by him before it is too late.’

‘Is he capable of that?’

‘Oh yes.’ Ay put a finger round his lips. ‘My granddaughter can conceive.’

‘Or is she your daughter?’ Pentju taunted.

‘My granddaughter,’ Ay replied evenly.

‘And if Tutankhamun doesn’t beget an heir?’ I asked. ‘If he dies childless, where will the Kingdom of the Two Lands go?’

I shall never forget Ay’s reply, in that chamber on that darkest night, for it brought to an end a period of my life. At first he didn’t reply, but just sat, head bowed.

‘So?’ I repeated the question. ‘To whom would Egypt go?’

‘Why, Mahu, Baboon of the South, Egypt will go to the strongest.’

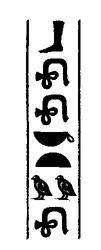

Metut ent Maat

(Ancient Egyptian for ‘Words of Truth’)

(Ancient Egyptian for ‘Words of Truth’)

Other books

The Valentine's Arrangement by Kelsie Leverich

Claire Delacroix by The Temptress

Prince of Fire by Daniel Silva

The Hating Game by Talli Roland

Crave by Sierra Cartwright

400 Boys and 50 More by Marc Laidlaw

Art of Betrayal by Gordon Corera

Blessed are the Dead by Kristi Belcamino

The Greek & Latin Roots of English by Tamara M. Green

Appalachian Dulcimer Traditions by Ralph Lee Smith